It’s 1876 and two of America’s most revered writers have decided to collaborate on what turned out to be one of the most disastrous plays in American dramatic work – and one that would severely damage a budding literary friendship.

The two writers in question, Bret Harte and Mark Twain, were at the top of their game when they began drafting the script for what would become Ah Sin, a play primarily about the propagation of Chinese culture and values and the reaction to this cultural shift in a small gold mining community.

The two writers in question, Bret Harte and Mark Twain, were at the top of their game when they began drafting the script for what would become Ah Sin, a play primarily about the propagation of Chinese culture and values and the reaction to this cultural shift in a small gold mining community.

Current political landscape aside – anti-Chinese sentiment was on the rise while Harte and Twain were completing early drafts of the play, which debuted on the cusp of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned all immigration to the United States from China – the paring of Harte and Twain seemed like a match made in heaven.

Harte, a poet, journalist and short fiction writer, had made a national name for himself by chronicling the romance and wonder of the California gold rush. Often rendered as tall-tales, Harte’s bombastic stories detailed the lives of miners, gamblers, tradesmen, and other fortunes-seekers who threw caution to the wind in the hopes of literally striking gold in the California mountains.

Best known for the stories "The Luck of Roaring Camp" and "The Outcasts of Poker Flat," both of which explore fictional, down-on-their-luck-mining towns and the characters that populate them, Harte was also an editor for a number of magazines and newspapers, including Overland Monthly, for which Harte’s friend and future collaborator Mark Twain was a frequent contributor.

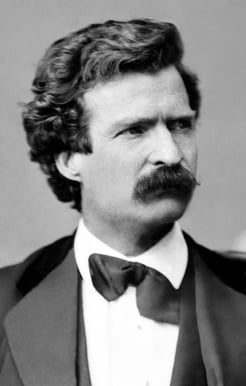

While not quite the literary stalwart of Harte’s stature, Twain was making a name for himself publishing short stories that also exposed readers to mining life.

Having worked as a miner, printer, typesetter, and river boat pilot before moving westward to focus on journalism and fiction, Twain was viewed as one of the foremost practitioners of what some scholars call ‘pioneer fiction,’ a moniker that was further cemented with the publication of the short story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" in 1865, which brought national and international acclaim.

Having worked as a miner, printer, typesetter, and river boat pilot before moving westward to focus on journalism and fiction, Twain was viewed as one of the foremost practitioners of what some scholars call ‘pioneer fiction,’ a moniker that was further cemented with the publication of the short story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" in 1865, which brought national and international acclaim.

The stage was set. Harte and Twain: friends and artists keen on crafting a work of dramatic art that captures the fervor of the moment in these small mining communities that dot the Californian terrain – the struggle, the hope, the fear, and the faith of those digging for a more prosperous future.

What could possibly go wrong?

Enter the conceit of the play.

It’s unclear how the decision came to be, but Harte and Twain decided to center their play on an adaptation of one of Harte’s more well-known poems: "The Plain Language of Truthful Jones," with an alternate title of "The Heathen Chinese."

Told from the point-of-view of the title character, Ah Sin, the poem concerns itself with Sin’s day-to-day experience as a member of a small mining community. The poem depicts Sin as a man subject to much prejudice because of his heritage, a common tide that was rising throughout the country during the 1850s and 1860s as more and more Chinese immigrated to California in search of work. As a result, anti-Chinese demonstrations and riots were not uncommon through mining and railroad country.

Conflict between Harte and Twain ensued almost immediately as the two began drafting and revising the script, in large part due to how Ah Sin should be portrayed – either as an illustration of the growing tensions between American and Chinese miners, or as merely stereotype used in a pawn-like manner to convey real life in mining communities – although some scholars assert dispute over a loan of money also played into the divide between Harte and Twain.

Literary experts appear to be split over which author was on what side of the debate: some argue Twain pushed for the more stereotypical approach, while others believe Harte advocated for that angle.

Frustrations mounted. As evidenced in letters Twain wrote to a friend, W.D. Howells, he began experiencing doubt about whether the project would come to fruition:

“I am all out of patience with Harte,” wrote Twain, who lamented what he considered watered-down edits by Harte. “The play entertained me hugely, even in its present, crude state.”

By the start of 1877, Harte and Twain were no longer in dialogue on the project. Twain took up the mantle and completed both the script and rough blocking of the play prior to its Washington, D.C. opening, while at the same time blaming Harte for the collapse of their partnership.

Whether in statements to the press or in his personal letters, Harte remained relatively silent about the play, the fractious relationship between Twain and himself, and the critical and commercial reaction to Ah Sin upon its initial performance – even years later, after Harte had moved to Europe for the latter portion of his life, he very seldom discussed the experience.

Ah Sin opened to mixed reviews and tepid ticket sales in May of 1877 – a very limited run of the production also took place, at Twain’s urging, in New York City that July. Much like the play’s authors, critics struggled over how to interpret Sin’s character, whether as a symbol of the time or as a straw-man-esque object for the other characters to knock down.

Call it life imitating art, but perhaps the great irony of the Harte/Twain collaboration was that the end result was just as underwhelming as the process in which the play was created.