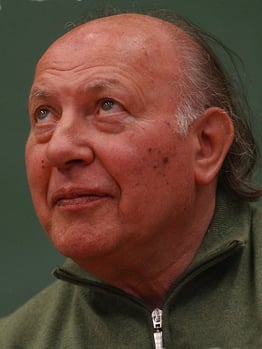

On March 31, 2016, author, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust concentration camp survivor Imre Kertész passed away. Today, we pay tribute to him and all that he taught us through his life and work.

To experience the Holocaust before the word was invented, before it had historical context, before it was what it has become in our cultural narrative, when it was just something that was occurring, when the larger questions of humanity were beyond reason and the truth of what was necessary boiled down to moment-to-moment survival...this is the story of the man who won the Noble Prize in Literature in 2002, Imre Kertész.

A teenager at the time, Imre Kertész was a prisoner in Auschwitz and Buchenwald and based his writings on those experiences. After being liberated from Buchenwald camp in May of 1945, Kertész found work as a journalist, but he was at odds with the newspaper he worked for and was dismissed from Világosság because of the communist regime. He supported himself as a translator and eventually began writing for himself.

A teenager at the time, Imre Kertész was a prisoner in Auschwitz and Buchenwald and based his writings on those experiences. After being liberated from Buchenwald camp in May of 1945, Kertész found work as a journalist, but he was at odds with the newspaper he worked for and was dismissed from Világosság because of the communist regime. He supported himself as a translator and eventually began writing for himself.

His novel Sorstalanság (Fateless), published in 1975, features a young man, Köves, who survives through pure conformity. Köves is no more angry or introspective about his time in the camps than he is about an earthquake or fire. He seeks only to survive, and regards and reports on the atrocities around him in a child-like observational style. Kertész used this point of view both as a mirror of his own feelings, but also as a stylistic choice that served as a metaphor for arrested development under regimes such as the Nazi party. He said, “I invented the boy precisely because anyone in a dictatorship is kept in a childlike state of ignorance and helplessness.”

This book, published a decade after it was written, solidified Kertész as a unique voice on a topic and a time so often discussed and written about. Once published and well received, two more books starring the young survivor were written, creating a trilogy. A kudarc (1988; The Failure) and Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért (1990; Kaddish for a Child Not Born) continued the story of young Köves. In this book he accounted for his life before the camps, and recognized that at Auschwitz, he felt most at home—that this was his time to choose to conform, to choose to survive, and that before Auschwitz, he had an unhappy life.

What sets the narrative of these books by Imre Kertész apart from the writings and depictions produced by others on the same topic was his unapologetic perspective that deeply differed from the expected personal account of a survivor. In his view, in his words, you will not find what he referred to as the “Kitsch” of something like Schindler’s List. To have a voice as loud as Spielberg’s telling a tale that is not personal—that cannot then be authentic—while still striving for “truth” regarding the experience of surviving in the camps, to Imre Kertész, was both moot and insulting. He found the suggestion at the end of the film—that the individuals who walked out of the camps were healthy and quickly recovered—to be especially egregious.

What’s more, he saw this experience, this atrocity, and the essence of the Holocaust as unremarkable in the grander story of humanity. For Kertész the killing and torture of millions of Jews was just one instance of humanity at its most authentic and pure. Spielberg’s movie, and other triumphant narratives like this, seek to place the Holocaust in the past and to leave it there as the one terrible thing that happened. Kertész’s stance was that terrible things happen because of the nature of humanity, and that the other nature is that of pure survival, without morality or self-aggrandizing or guilt.

It was this unapologetic worldview that shaped his thinly veiled autobiographical fiction. Having regarded his time in the camps as some of the happiest he’s known, he may shock those looking for a martyr's tale. What he described is much more profound. Having been near death as a young person formed in this environment, he embraced life and found freedom in not dying and enjoying those moments of peace, of rest, of life.

When trying to express this sentiment within his novel, one that he wrote after the war and within a dictatorship, with the assurance (given the reality) that it would never be published, Kertész felt that same unburned freedom—that same hopelessness that creates opportunity—and wrote privately and without worry of offending or finding approval from an audience or publisher, and he produced a truly authentic and personal account of his time in the camps.

His 2002 Nobel Prize was awarded to him because of his representation of the individual. The larger narrative of history can swallow such a perspective, and his work focused squarely on telling the story of the person and letting the context speak for itself. As an artist, he objected the idea that thinking about the experience and expressing the feelings therein was in any way valuable or healing. Though it had been his focus, he had concentrated only on his own, personal story, and found contempt in the way that holocaust narratives have been “stolen from its guardians and made into cheap consumer goods.”

The glut of narratives, movies, novels, and memoirs—all with the same basic narrative—brings his words and perspective into a context that is not entirely welcome or akin to what he had to say. His narrative, written decades after the experience and a full ten years before it was published, refuses the common narrative and embraces one that he found authentic because he knew it to be true. The feeling expressed by Kertész was that of being robbed of the only thing left to survivors: their own story, as they experienced it.

Sources

-Theil, S. (n.d.). The Last Word: Imre Kertész A Voice of Conscience. NEWSWEEK INTERNATIONAL.

-Kertész, I. (n.d.). Who Owns Auschwitz? Retrieved March 2, 2016, here.

-Zielinski, L. (2016). Imre Kertész, The Art of Fiction No. 220. The Paris Review. Retrieved March 2, 2016, here.

-Just-liberated Ebensee concentration camp survivors wear (and some show to the camera) metal tags bearing ID numbers on cord bracelets or necklaces. [Photograph]. (1945, May 7). National Archives and Records Administration.

-Imre Kertész (1929-) Hungarian writer II. by Csaba Segesvári.JPG [Photograph]. (n.d.). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository In Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved March 2, 2016, here.