Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon has been hailed by the Times Literary Supplement as “the most significant English-language poet born since the Second World War.” In addition to earning a bundle of superlatives, he is also a professor at Princeton University and the poetry editor at the New Yorker. He is musically inclined, and plays guitar in the rock band, The Wayside Shrines. He released a volume of lyrics called The Word on the Street in 2013. And, before his day jobs were entirely belletristic, he worked as a TV and radio producer for the BBC.

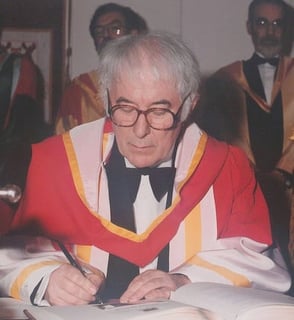

It is probably not surprising that such an accomplished poet was precocious. As a university student in Belfast, he was taught by Nobel laureate and poet Seamus Heaney. The reality is a tad fuzzy—even Muldoon can’t recall it precisely — but the legend goes that the young Muldoon sent his poetry to Heaney, asking him to tell him what was wrong with it. Heaney replied, tersely, with “Nothing.” This intergenerational bond, from one great Northern Irish poet to another, was for Muldoon, more than a special meeting of minds.

It is probably not surprising that such an accomplished poet was precocious. As a university student in Belfast, he was taught by Nobel laureate and poet Seamus Heaney. The reality is a tad fuzzy—even Muldoon can’t recall it precisely — but the legend goes that the young Muldoon sent his poetry to Heaney, asking him to tell him what was wrong with it. Heaney replied, tersely, with “Nothing.” This intergenerational bond, from one great Northern Irish poet to another, was for Muldoon, more than a special meeting of minds.

Seamus Heaney was substantially responsible for jump-starting Muldoon’s literary career. Heaney connected this young talent with the poetry editor at Faber & Faber, enabling Muldoon to publish his first collection of poetry while he was still a student, at the age of 21. After graduation, he began working for the BBC in Belfast, before finding work in academia. He taught at Cambridge and East Anglia, before working at Oxford as a poetry professor until 2004.

Today, Muldoon has stable roots in America, where he now resides. He lives in Princeton, with his two children and his wife, in a house which was once a tavern where George Washington spent some time. He recently showcased his New York office for a New York Times magazine feature about where writers write. One may agree that Muldoon has quite impressive taste in antique furniture.

But what of his poetry? Few would protest that Muldoon is a grand wordsmith. He is perpetually after the most precise language, whether it means playing with Irish dialects, arcane disciplines, or whatever mood fits his work. Take this threnodic line he wrote in his most recent book, One Thousand Things Worth Knowing, dedicated to his recently departed hero: “I cannot thole the thought of Seamus Heaney dead.” Thole, or "to tolerate or bear without evidence," is an archaic Scottish word that many contemporary dictionaries are likely to neglect. Yet for the remembrance of Heaney, the fellow Celt who famously vivified Beowulf in his masterful translation, Muldoon’s labor is expertly placed.

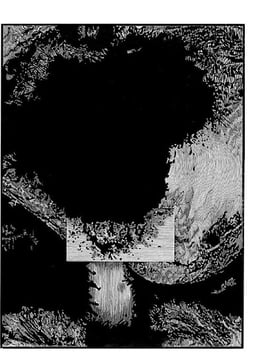

Proving that his work is not likely to get boring any time soon, Paul Muldoon’s recent project is Encheiresin Naturae, published this year by Nawakum Press. The project, whose title is borrowed from a line from Goethe about the alchemist's manipulation of nature, originated with artist Barry Moser. Moser's original engravings were the backbone of the book. Muldoon, using his artwork as inspiration, composed a heroic crown of sonnets to elegantly complement them. This audacious “crown” follows a specific construction. Each sonnet takes on one aspect of a theme that unites every one. Each sonnet is linked, too, as the final line of the preceding sonnet is to begin the current one. Then, a final sonnet emerges, made up of the first lines of the first fourteen sonnets, in order. As a visual, textual, artisanal, and artistic fine press experience, Encheiresin Naturae awards its readers with its manifold rich layers.

Encheiresin Naturae is exactly the kind of project that could provide welcome variety for even someone as artistically adventurous as Muldoon. The book is supremely well-crafted by Nawakum. Its printing runs an intimate fifty copies (of which only forty are available through vendors), and each illustration was pressed from the original block. For the writer who’s been declared the best of his generation, who plays guitar in a rock band and edits poetry for the New Yorker, we wouldn’t expect anything less interesting.