William Henry Ireland forged Shakespeare, and the Russian secret police fabricated records from a secret society. Literary hoaxes can be entertaining, dangerous, or humiliating. Today is our final installment on famous literary hoaxes. (Be sure to check out Part One and Part Two.)

Miseducation in Native American History

When The Education of Little Tree was published in 1976, it was an immediate success. The book was billed as the memoir of the orphaned author, who grew up with his Cherokee grandparents. It sold over nine million copies and made school reading lists across the country. The Education of Little Tree did receive some criticism from the Cherokee tribe for its inaccurate depiction of Cherokee language and tradition, but that did little to slow sales.

Then in 1991, it was revealed that author Forrest Carter was actually Asa Carter. Carter had been a speechwriter for George Wallace, a member of the White Citizens Council and the Ku Klux Klan, and the 1970 Georgia White Supremacists candidate for governor. He had no Cherokee blood and had fabricated The Education of Little Tree in its entirety. Shockingly, the book's popularity hardly waned; it was reclassified as fiction and continues to appear on school reading lists to this day. It was briefly added to the ranks of Oprah's Book Club, but quickly removed.

A Journalist Turns to Forgery

Not all forgeries are created equal, and the Hitler diaries are a classic example. The diary of Adolf Hitler was supposedly recovered from an airplane crash shortly after the end of World War II and smuggled out of East Germany. They eventually "ended up" in the hands of journalist Gerd Heidemann, who sold them to the German newspaper Stern and its parent company for quite a tidy sum. The newspaper immediately announced the discovery of the journals, which recounted Hitler's rise to power and later years as Nazi dictator. Experts were immediately both fascinated and skeptical--especially because the newspaper restricted access to the documents, allowing only few World War II experts brief access.

Eventually excerpts of the diaries were released. The story began to fall apart immediately, and at the request of the West German federal government the West Germany Federal Archives stepped in to authenticate the documents. Experts made their proclamation on May 6, 1983: what they found was not only that the diaries were forged, but that they were truly deplorable fakes: the handwriting obviously didn't match known samples of Hitler's writing. Furthermore, they were made of modern materials and much of the content was plagiarized from other well known sources. Konrad Kujau, who was responsible for the forgeries, was convicted of fraud along with Heidemann. Both men went to jail. But the millions they received in payment for the fake documents were never recovered.

A Legendary Forger Gets Desperate

Mark Hofmann was an antiquarian dealer with incredible scouting skills; throughout the 1980's he unearthed a series of truly exceptional documents. These included a previously undiscovered poem by Emily Dickinson and signatures of historical figures like George Washington, Daniel Boone, Mark Twain, and Paul Revere. Hofmann also specialized in documents from the early days of the Mormon Church. One of these was the Salamander Letter, supposedly written by Martin Harris to William Wines Phelps. Harris had been a scribe during the translation of the golden plates and assisted in financing the first printing of the Book of Mormon. The letter detailed a different account of Joseph Smith's recovery of the golden plates. According to this letter, a salamander appeared when Smith dug up the golden plates and transformed into a spirit that refused to give Smith the plates unless his (then deceased) brother Alvin was present. The account corroborated urban legend that the Smith family had dug up Alvin's body to use in a magical ceremony.

Mark Hofmann was an antiquarian dealer with incredible scouting skills; throughout the 1980's he unearthed a series of truly exceptional documents. These included a previously undiscovered poem by Emily Dickinson and signatures of historical figures like George Washington, Daniel Boone, Mark Twain, and Paul Revere. Hofmann also specialized in documents from the early days of the Mormon Church. One of these was the Salamander Letter, supposedly written by Martin Harris to William Wines Phelps. Harris had been a scribe during the translation of the golden plates and assisted in financing the first printing of the Book of Mormon. The letter detailed a different account of Joseph Smith's recovery of the golden plates. According to this letter, a salamander appeared when Smith dug up the golden plates and transformed into a spirit that refused to give Smith the plates unless his (then deceased) brother Alvin was present. The account corroborated urban legend that the Smith family had dug up Alvin's body to use in a magical ceremony.

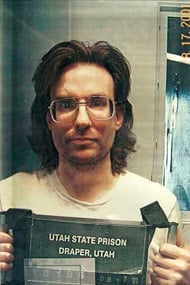

Though experts originally deemed the letter authentic, they soon had doubts. Hofmann's reputation was on the line, and the stakes were high. By 1985, Hofmann was working on selling Oath of a Freeman to the Library of Congress. The 1639 document was the first printed in the British American colonies, and only 50 were made. None were extant, and Hofmann stood to make a fortune if the deal went through. Desperate to distract people from the Salamander Letter, Hofmann actually sent bombs to people. Two people were killed, and Hofmann injured himself when a third bomb prematurely detonated in his car. The explosion triggered an investigation, and detectives discovered a sophisticated studio for producing counterfeit documents in Hofmann's basement. Hofmann is now notorious as one of the most accomplished and wily forgers of all time.

An Imaginary Meeting of Literary Minds

On April 10, 2013, Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Califorina Eric Naiman published an article in the Times Literary Supplement. He exposed the mythic meeting between Charles Dickens and Fyodor Dostoevsky as a complete fabrication, the invention of one AD Harvey. Harvey, Naiman discovered, had created an intricate network of academic personae that had commented on and criticized one another's work for the past three decades. The man behind the deceit: Arthur Harvey, a disillusioned independent scholar who feels shut out by the academic community. Harvey recently agreed to an interview with The Guardian, where he admitted Naiman hadn't even uncovered all of his identities. Harvey argues that his work was consistently rejected when he submitted them to journals under his own name, so he began submitting under pseudonyms--and getting his work published. Later Harvey even resorted to plagiarizing himself in the journal History to corroborate his suspicions about the shortcomings of modern peer-reviewed academic journals.

Harvey first wrote of the meeting between Dickens and Dostoevsky as Stephanie Harvey in the Dickensian in 2002. Though the write-up triggered red flags for some scholars, Harvey's account went largely unquestioned; indeed, it was cited in Michael Slater's 2009 biography of Dickens, and again in Claire Tomalin's 2011 biography. Harvey says that he didn't undertake the hoax out of malice. "Yes, I have some of the instincts of the troublemaker. But the other thing is I am creative and inventive....It was a jeu d'esprit. Yes I was misleading the editor of the Dickensian, but it's caveat emptor." Harvey hadn't counted on Americans' voracious interest in Dickens, however. "What I hadn't bargained for," he said, "was how much interest there would be in the Dickens and Dostoevsky thing in America. It wouldn't have been noticed if it hadn't been for the Americans."