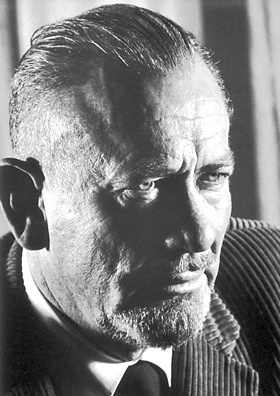

John Steinbeck, born on February 27, 1902 in Salinas, California, would become one of American's most notable authors. Steinbeck established himself as an author in an era when accomplished authors held considerable clout. As a result, he one day found himself in a unique position: he held the upcoming United States presidential election in his hands.

Steinbeck's Friendship with Adlai Stevenson

Adlai Stevenson emerged from Illinois an unlikely presidential candidate. A first-term governor of Illinois, he hadn't sought the post, but President Harry S. Truman decided not to seek a second term. He and other prominent Democrats suggested that Stevenson run and offered his support. Stevenson urged them to stop their concerted efforts to gain him the nomination, both publicly and privately. Ultimately, however, they prevailed. Stevenson agreed to the nomination and moved forward with the candidacy.

Adlai Stevenson emerged from Illinois an unlikely presidential candidate. A first-term governor of Illinois, he hadn't sought the post, but President Harry S. Truman decided not to seek a second term. He and other prominent Democrats suggested that Stevenson run and offered his support. Stevenson urged them to stop their concerted efforts to gain him the nomination, both publicly and privately. Ultimately, however, they prevailed. Stevenson agreed to the nomination and moved forward with the candidacy.

Stevenson faced Eisenhower in a new medium: television. Read more about the campaign, via Radio Diaries.

By this point, Steinbeck—and countless others across the nation—had been entranced by Stevenson's eloquent speeches. Stevenson had captured the nation's attention with his speech at the 1952 Democratic Convention, held in Illinois. As that state's governor, it was his job to make opening remarks. By the end of the speech, Steinbeck had fallen "madly for Adlai." He said of Stevenson, "I love the clean, clear writing....As a man, I like his intelligent, humorous, logical, civilized mind." That same year, Steinbeck penned a four-page introduction to a book of Stevenson's speeches.

The two grew to be fast friends. They soon discovered a shared love for agriculture, dogs, liberal politics, and the legend of King Arthur and the Round Table. Steinbeck regularly wrote to Stevenson and visited his country home on multiple occasions. He even visited Stevenson as part of the journey documented in Travels with Charley.

Bitter Loss and a New Threat

Stevenson was trounced by Dwight D. Eisenhower, but the bitter loss didn't deter him from running again in 1956. This time, Steinbeck signed on to the campaign and wrote Stevenson's speeches.

Still, Steinbeck's mighty pen and Stevenson's silver tongue proved no match for a national hero, and Stevenson again lost the presidency to Ike.

Amazingly undeterred, Stevenson began planning another run in 1958. Democrats believed that Richard Nixon was the most likely Republican nominee, and he was already receiving plenty of media attention (even from the Democrats). Stevenson's staff saw a looming "Nixon danger" and knew they must act fast to quell Nixon's already growing popularity.

Unconventional Tactics

Unconventional Tactics

Stevenson's staff knew that the same old strategies from previous campaigns simply weren't enough. Thus Stevenson's right-hand, William McCormick Blair, Jr, enlisted the assistance of Stanley Frankel. Frankel was the brother-in-law of Stevenson's law partner Newton Minow. Frankel had already suggested more aggressive tactics during the 1956 election when he'd advised Stevenson to spend up to $500,000 advertising President Eisenhower's heart troubles. But Stevenson had played more honorably, always addressing and discussing the president with reverence.

This time, Frankel and his cohorts drafted an eight-page memo outlining a truly unconventional approach. They argued that "public relations cliches" would be completely insufficient against Nixon and his media machine. Frankel proposed a novel as a "single, major and...practically certain-of-success project." He noted that the novel should clearly be about Nixon, like Robert Penn Warren's All The King's Men, about Huey Long. The goal of the novel: to "lay [Nixon] and his motives bare" and "destroy him in his shot at the presidency."

The group entertained several candidates for writing this novel: John Hersey (Hiroshima), Edwin O'Connor (The Last Hurrah), and Henry Morton Robinson (The Cardinal) were all suggested, but Steinbeck was by far the favorite. His friendship with Stevenson was obvious (as was his dislike of Nixon and Eisenhower), and Steinbeck's reputation ensured that the novel would be widely read. After all, in 1958 writers were celebrities and trendsetters in their own right. Steinbeck had also earned a reputation as a moral figure.

A Crazy Idea?

By today's standards, it seems highly unlikely that a novel would have any impact on a presidential election. But in 1958, this approach was truly ingenious. Steinbeck was famous, and bestsellers were still widely relevant to popular culture. The relative peace and prosperity of America meant few distractions from domestic events like new (and possibly controversial) novels. Even ten years later, when Nixon ran for his second term, this strategy would have failed miserably; by then the nation was embroiled in the Vietnam conflict and a bitter civil rights struggle.

However, the tactic may have worked for Stevenson...if Steinbeck hadn't declined to write the book. While we might have expected Steinbeck to protest such an underhanded ploy on moral grounds, he didn't. Instead, in a June 7, 1958 letter to Blair, he says that he simply didn't think the plan would work. "Did [Jonathan] Swift ever win an election?...The more I think of it the less I am convinced it is a good, meaning effectual, plan at all."

Ultimately Stevenson's worry about Nixon was premature; he should first have focused on securing the Democratic nomination. Instead he complacently sat by while John F. Kennedy aggressively gained support among the Democrats. This final blow marked the end of Stevenson's attempts at presidency. Yet he and Steinbeck both have earned distinct places in American history. And Stevenson's speech book that contains Steinbeck's introduction has become a collectible rare book in its own right.

Portions of this post have been previously published on our blog.

Sources here and here.