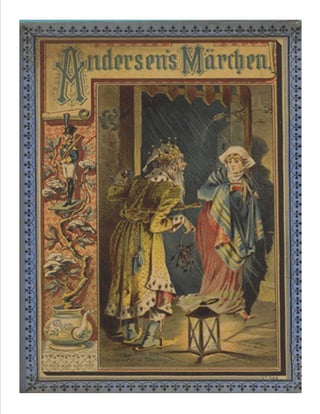

Hans Christian Andersen is a strange and fascinating figure who wrote a great many stories for children. His name is synonymous with love, splendor, and the wonderment of childhood. His own childhood was less than perfect, existing in deep poverty as the child of an illiterate washerwoman. He left his first life at 14 to find a new one with a wealthy family. He spun this fortune into a career in the arts, finding his mark with children’s stories in 1835. From there he remained a servant to the child’s ear, and his work has spawned retellings, both comical and romantic, for generations since.

Disney has picked up more than a few of his tales, and others have been animated, performed, retold, and embraced as fun and moving stories. However a romp within the actual original text of many of them reveal a certain level of sadness, despair, ugliness, and outright weirdness that we tend to overlook when speaking the name Andersen. Let’s take a closer look at a few that are particularly famous and particularly ghastly when we take off our rose-colored glasses, put on our spectacles, and peer really close.

1. Thumbelina

A tiny girl, a loving mother, a grand adventure. This is what Thumbelina calls to mind, that of a childless woman who hoped just hard enough for the universe to give her a tiny daughter, one no bigger than a thumb, hence the name.

A tiny girl, a loving mother, a grand adventure. This is what Thumbelina calls to mind, that of a childless woman who hoped just hard enough for the universe to give her a tiny daughter, one no bigger than a thumb, hence the name.

Thumbelina, however, had a torturous existence in the original story. Purchased as a seed from a witch, she is kidnapped by a large ugly toad in hopes of being married to said ugly toad’s son. Thumbelina is so horrified that she weeps loud enough to be heard by the minnows in the water, who chew through her lily pad stem and set her free. Her grief and misery does not end here...not by a long shot. Instead, she is taken in by a complicated field mouse who is, on one hand, a very dour and generous old woman, and on the other a stern and traditional task master. The field mouse looks to (you guessed it) marry Thumbelina off to her friend the mole, who though blind and introverted and unkind, is rich. Thumbelina seems to have no say in the matter and cries often, only to be told, more or less, to “suck it up” by her supposed protector, the old field mouse. As she recognizes this horrible existence, Thumbelina finds comfort in trying to save and nurse back to health a bird once thought dead that was caught in the hallway of the mole’s underground lair. The bird is, indeed, alive, and after some of Thumbelina’s efforts, is healthy and well and flies away.

On the day of the wedding, Thumbelina goes outside one last time to see the sun, and is saved, at the last possible minute, by her bird friend. He takes her to the land of flowers and drops her in a blossom where there is a tiny prince, just her size, to whom she becomes (happily) married.

There’s so much here. First, of course, there’s the “childless woman in search of a child” trope, but that is so quickly abandoned it almost seems unfair. This poor woman was willing to resort to witchcraft in order to have a child, and when the delivery wasn’t a bouncy baby girl, but rather a tiny child that she had to grow in a flower pot, she loves her anyway, and gives her a home. Her love, acceptance, and efforts are all rewarded with only a footnote in the larger tale of Thumbelina. Even the child herself doesn’t mourn for her mother as much as she mourns for sun or the sounds of birds singing.

Marriage, and in this case the marriage of a tiny child, seems to be the only possible end result to the existence of Thumbelina. First by the old toad, then by the field mouse, then by the mole, and finally by Andersen himself. You would think the bird would bring back the child to her mother since, after all, she is a tiny child. Instead, he takes her to get married, which was what the reader might think she’s been avoiding for the entire tale!

And what is with the field mouse? She takes in a strange girl child, but then seems to sell her off to her old rich “friend” and isn’t concerned about her well-being or future. There is no kindness here, and with the casualness that she has towards this task, one must wonder if Thumbelina was about to be his first wife, or one of many ill-fated brides that fell into this weird relationship of mouse and mole and the outside world.

Finally, who is this witch? Does she pilfer through the land of flower people and steal seeds to sell to childless women? Is anyone concerned about this? Are the flower people aware, and is this a normal thing for them? To have one of their own returned by a bird? Do they have plans to thwart this horrible woman and her seed stealing ways? It just seems like a strange plot point that isn’t really addressed.

All in all, a very creepy tale about child brides, tiny people, and witches.

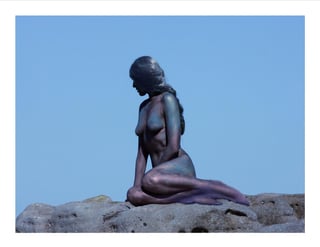

2. The Little Mermaid

Yes, we all love Ariel with her red hair and strong opinions. Under the Sea ran on a continuous loop through much of the '90s, and when she was finally given the happy ending she deserved for loving so deeply, it reaffirmed our knowledge that love is real and good things happen to those who follow their hearts, even if they have to sacrifice a little (like a voice) here and there to get what is fated.

Yes, we all love Ariel with her red hair and strong opinions. Under the Sea ran on a continuous loop through much of the '90s, and when she was finally given the happy ending she deserved for loving so deeply, it reaffirmed our knowledge that love is real and good things happen to those who follow their hearts, even if they have to sacrifice a little (like a voice) here and there to get what is fated.

However, going back to the text, things get very dark very quickly. There is a mermaid, she does save a handsome prince from drowning, and that saving does create an obsession that can be called love that eventually results in her making a Devil’s deal with a sea witch. There the popular version and the original take a turn.

In the original text she does sacrifice her voice, but not in a painless way. Instead her tongue is physically cut out of her body and her new legs (or “two stumps” as the sea people refer to them) are graceful and beautiful, but every move and step incurs knife-like pain for the mermaid. And yet, she goes happily into this arrangement, tongueless and feeling stabbed morning, noon, and night, all in hopes of gaining the love of the prince. She does this in part because she is in love with him, but the stakes are actually much higher. Mermaids in this story live 300 years but then are fated to become ocean foam and nothing more. Humans live a much shorter time, but they have a huge advantage: eternal life in the kingdom of heaven. If the mermaid can get the prince to fall in love with her, she gets to use his human password to get into the kingdom and therefore gain a human soul and all that comes with it. This, above anything else, is her true goal and the love of the prince and a soul to take to heaven are referred to in the same breath each and every time in the original text.

The prince, for his part, is amused with his “foundling” but that’s about it. In fact, he has her sleep on a cushion outside his door like a pet. What a guy. When he meets a princess from a neighboring kingdom, she resembles the woman who saved him enough (but not, apparently, as much as the woman who actually saved him who has been sleeping outside his door this entire time) that he falls madly in love, proposes, and the former mermaid finds herself leg stabbed and voiceless throughout their wedding day.

On the day after the wedding she knows she will now be turned into foam on the ocean and patiently awaits her fate on the deck of the marriage ship. However, a few minutes before, her sisters show up, shorn, hairless, and offer up a knife. They have traded their hair to the sea witch for it (which seems like a small price since hair, unlike a tongue, grows back), and the Little Mermaid must stab the prince in the chest and let his blood wash on her new legs, which will then turn into a mermaid’s tale so she’ll have her 300 years back again. Problem solved.

Despite her deep love for this man, she does consider this. After all, if he had loved her back she’d have eternal life. Instead, she’s now moments away from becoming ocean foam and what with the leg pain and no tongue, she’s kind of done a lot for him (we’re not even going to mention the whole “saving his life” thing). So she goes in where he is sleeping with his wife and stands over the bed, as one does, with the knife, but then hears him call out his wife’s name in his sleep. This, for some reason, convinces her not to kill him, but rather to throw the knife into the ocean and then throw herself in after it. As she does this, the ocean turns blood red and for a moment she feels herself turning into ocean foam.

BUT, all is not lost. She does not become foam, but she is not saved either. Instead, there’s a third option, one not discussed until this very last moment. She is surrounded by voices and visions of figures and is told she is now one of the “daughters of the air” and gets to be this incarnation for the next 300 years. She has been rewarded for all she did (saving the prince’s life, sacrificing her tongue, enduring pain in hopes of an immortal soul, not murdering him, sacrificing her life and so on) by having this opportunity. If she works as a daughter of the air and cools farmers at work and blows windmills for grain and moves ships on the sea, she will be given an immortal soul. There is one extra detail: if she blows her way into the room of a child and that child is obedient and well-mannered she gets a year off of her sentence. However, if that child is having a tantrum or being bad, she will cry in sorrow for what she sees and each tear will add a day to the existence of wind blowing.

BUT, all is not lost. She does not become foam, but she is not saved either. Instead, there’s a third option, one not discussed until this very last moment. She is surrounded by voices and visions of figures and is told she is now one of the “daughters of the air” and gets to be this incarnation for the next 300 years. She has been rewarded for all she did (saving the prince’s life, sacrificing her tongue, enduring pain in hopes of an immortal soul, not murdering him, sacrificing her life and so on) by having this opportunity. If she works as a daughter of the air and cools farmers at work and blows windmills for grain and moves ships on the sea, she will be given an immortal soul. There is one extra detail: if she blows her way into the room of a child and that child is obedient and well-mannered she gets a year off of her sentence. However, if that child is having a tantrum or being bad, she will cry in sorrow for what she sees and each tear will add a day to the existence of wind blowing.

Of course, she is overjoyed, and who wouldn’t be? And what child wouldn’t enjoy this tale? You have unrequited love, lots of pain, physical disfigurement, witchcraft, almost-murder, and then a big heaping pile of guilt at the end. If you are good, you are a small part of freeing this poor woman from her multiple century-long misery. However, if you are bad you make her cry, and also lengthen her already lengthy sentence. After all she’s been through, can’t you just eat your porridge and go to sleep and let the lady get to heaven, which she clearly deserves more than that prince who lets mute women sleep on floors and ignores their sacrifices?

An exciting story, with lots of twists and turns, and a dark and almost painfully tragic edge that is truly a staple of the Andersen tale.

3.The Steadfast Tin Soldier

Even the title sounds noble and true. He is tin, but that doesn’t stop him from being noble and full of love. Add the extra element of only having one leg, and we have quite a story. It’s a wonder that Hollywood didn’t come knocking more loudly, though a version was included in the 2000 film Fantasia. The more accepted and familiar adaptation of this tale is another case of love winning out and truth and valor being the victors.

Andersen’s original tale, however, was dominated by the same peculiar, dark, spindly edges that punctuate all of his stories. First, the tin soldier is the unique brother in a squad of identical brothers, because he only has one leg. This is what makes the “Steadfast” part of his title a little sad. Don’t worry. It gets sadder. The object of his affection is a ballerina who lives in a paper castle on the other side of the nursery. He has been set on a window sill and gazes at her from a distance. She is a typical ballerina, with a dress and a spangle sash, but what truly captivates him is that they have so much in common. You see, from his perspective she also only has one leg. Of course, she has two, but he can only see one, because she is in a dancing position and has her other leg stretched out behind her. From this, we get to observe his truly child-like perspective and need for the familiar, which is, of course, heartbreaking.

Naturally there is an enemy, a troll who lives in the tinder box, and who loves nothing more than to make bad things happen to good creatures like the one-legged soldier and the two-legged ballerina. This troll makes the window blow open and the soldier fall out. Soon the soldier, steadfast as is his nature, goes off on a truly strange series of adventures starting with a paper boat trip courtesy of two rough boys with no interest in his military service, and ending with finding himself on the inside of a fish. The fish is caught, sold, and delivered in record time, and in a deep and puzzling coincidence, to the same family that lost the soldier in the first place. Instead of being impressed by the current of fate that returned his beloved soldier to him, the child who had earlier looked up and down the street calling for him, instead grabs the one-legged man and throws him into the oven fire. There is no information as to his motive, but as this happens a gust of wind (probably called there by the equally motiveless troll) carries the ballerina into the fire also. The two of them burn up, but in the morning the maid finds that the soldier’s tin has been shaped into a heart and the ballerina has left behind her spangle, but that it is covered in soot.

Again, there is no real moral here, just a great deal of undeserved pain. The soldier was born imperfect, and loved with wild abandon another he saw as equally imperfect, while searching for solace and familiarity. For reasons beyond their control, the pair are met with death before their time, and what is left of them is significant only because it reflects on the pitifulness of their existence. She leaves behind beauty that is tarnished, and he leaves behind a physical representation of his one and only feeling: love. This is the heartbreak of Andersen’s stories: nothing good is rewarded, and pain sometimes serves as its own experience and nothing more. Children are heartless, love is pointless, and everyone is broken...and yet we love anyway. He seems as puzzled as we are and expresses it through torturing his characters into early and senseless deaths.

4. The Princess and the Pea

Authenticity, rather than true love, is the focus of this old tale. It has an element of the glass slipper narrative from Cinderella. There are those who are, and those who are not, and the only way to tell is with a simple test, in this case a pea. The prince in this story seeks not love, but a “true princess,” and though there are those who hold the title, he finds something “not right” about each of them. The story doesn’t elaborate or define what is lacking, but it does keep him a bachelor until a rain-soaked woman shows up at his doorstep in the middle of the night seeking a place to sleep and has only her word to claim that she is a “true princess.”

Authenticity, rather than true love, is the focus of this old tale. It has an element of the glass slipper narrative from Cinderella. There are those who are, and those who are not, and the only way to tell is with a simple test, in this case a pea. The prince in this story seeks not love, but a “true princess,” and though there are those who hold the title, he finds something “not right” about each of them. The story doesn’t elaborate or define what is lacking, but it does keep him a bachelor until a rain-soaked woman shows up at his doorstep in the middle of the night seeking a place to sleep and has only her word to claim that she is a “true princess.”

The queen, the prince’s mother, has her doubts, but creates a fool-proof test. She places a single pea under the mattress of her guest. Not satisfied with this, she then piles twenty mattresses on top of the single mattress and then offers the bed to the woman claiming royal blood. In the morning the princess complains that she didn’t sleep a wink and that her body feels bruised and battered after sleeping on such an uncomfortable mattress all night. The prince and queen rejoice as only a “true princess” would have a skin and body so sensitive that she would feel a tiny pea under so many mattresses. She and he are married and the story boasts that the pea was placed in a museum and can be seen today, so this is a “true story.”

This tale and the seeming lesson behind it have been celebrated in children’s books and plays for years and the world has accepted, without question, this odd and nonsensical assertion that physical sensitivity is a true mark of royalty. After reading the original, there might be readers who express more concern than acceptance with this supposed royal affliction. If a pea under 21 mattresses causes her body to be black and blue, what is the rest of her day like? Surely the stones in the street just on the other side of her shoe must rival the pain felt by the poor mermaid! How does she sit, stand, ride horses, or simply get through life? And why is physical sensitivity a positive? Wouldn’t constant skin irritation and pain be a detriment to the potential royal duties? The odder thing is that no other information about those the prince deemed “not right” and this fitful sleeper are shared. The other women are not said to be ill-tempered, rude, self-obsessed, unattractive, selfish, or any other kind of “not right.” It just seems to be a gut feeling that is only satisfied by proof through the inability to sleep on top of a pea.

There is also the curious house-guest arrangement of this tale. A princess arrives in the middle of the night and accepts, without question, the task of sleeping on a stack of mattresses. This does not bother her, and she gladly climbs a ladder (one must assume) to sleep on this tower of bedding. In the morning, rather than being appreciative, she complains and focuses on the one, tiny, element of her visit that was unsatisfactory. A strange sort of hospitality, a very strange response, and from this we are to nod in agreement that “Yep, this is royalty alright.”

There may be an argument here that Andersen may have not been celebrating how other-worldly and deeply sensitive royalty is, but pointing readers towards the opposite conclusion. To assume that royal figures feel and respond in a different way than the rest of us do; that they are too sensitive and delicate for normal life, and that this is why they do not have to work at the same level or deal with the same hardships, is as ridiculous as choosing a wife based on her lack of sleep after sleeping on a pea (which, by the way, would clearly be smashed by the weight of even a pillow, so there’s that also).

Andersen, Hans Christian. (2015). In The Columbia Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Andersen, H. C. (2004). Fairy Tales (T. Nunnally, Trans.; J. Wullschlager, Ed.). New York, NY: Viking.

Hans Christian Andersen, 1805-1875 [Photograph]. (n.d.). Library of Congress In Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. Retrieved March 2, 2016, here.