In Jorge Luis Borges’ 1941 story "The Library of Babel", he describes an infinite library containing volumes that feature every possible combination of symbols. At one point, some of the inhabitants of this library go on a rampage, wantonly destroying many of the unique, unread books. While many of their fellow denizens are outraged that works with no copies have been expunged forever, they eventually reason that if the books really are infinite, then any particular destroyed volume will have an accompanying volume that is almost completely identical, and that, really, no harm can be done. I’m not sure whether that should make us feel better or worse when we think about all of the lost and destroyed works of art throughout the literary millennia, but in honor of World Poetry Day, let’s take a look at some works of poetry that we’ll never be able to read.

The Poems of Sappho (c. 600 B.C.)

It may seem morbid, on a day set aside to appreciating the power of poetry, to dwell on works that have been lost to time, but it can be a nice reminder to read and reread the poems that we’re still lucky enough to have and to acknowledge the importance of preserving individual poems in addition to poetry as a practice. In the case of the ancient Greek poet Sappho, for instance, being held in great esteem wasn’t enough to ensure her work’s survival. Though she was one of the Nine Lyric Poets hailed as being particularly important to the genre, only 650 (of an estimated 10,000) lines of her poetry remain, many of them comprised of sentence fragments or even individual words. While rumors circulated for centuries that censors had systematically burned her works out of religious ire, it seems more likely that very few copies of her works ever existed to begin with, and that those that did weren’t preserved. Recently, the poet and classicist Anne Carson translated each of these fragments, even those of only one or two words, into English, giving non-specialists a sense of how powerful an oeuvre Sappho might have produced.

It may seem morbid, on a day set aside to appreciating the power of poetry, to dwell on works that have been lost to time, but it can be a nice reminder to read and reread the poems that we’re still lucky enough to have and to acknowledge the importance of preserving individual poems in addition to poetry as a practice. In the case of the ancient Greek poet Sappho, for instance, being held in great esteem wasn’t enough to ensure her work’s survival. Though she was one of the Nine Lyric Poets hailed as being particularly important to the genre, only 650 (of an estimated 10,000) lines of her poetry remain, many of them comprised of sentence fragments or even individual words. While rumors circulated for centuries that censors had systematically burned her works out of religious ire, it seems more likely that very few copies of her works ever existed to begin with, and that those that did weren’t preserved. Recently, the poet and classicist Anne Carson translated each of these fragments, even those of only one or two words, into English, giving non-specialists a sense of how powerful an oeuvre Sappho might have produced.

Margites (c. 800 B.C.)

Unsurprisingly, a large proportion of the works we know of but no longer have access to are from either Greek or Roman antiquity, with their existence known to us only from references in other texts. That’s how we've come by some of the fragments of Sappho that we have, and it’s how we know of Margites, a parody of Greek epics like The Iliad and The Odyssey (both c. 800 B.C.) that many believe was composed by Homer himself. The title character became synonymous with incompetence: Plato said of him that “he knew many things, but he knew them badly,” while a later philosopher would coin the term “mad as Margites.” The most significant reason it’s disappointing not to have access to the text, however, is that Aristotle uses it as an example in his Poetics (c. 335 B.C.), meaning that there will forever be a gap in our understanding of his philosophy. Though, the second half of the poetics (the part that deals with comedy) was also lost, so it may be a moot point.

Meanderings of Memory (1852)

Of course, the problem of losing works that one has cited is not strictly relegated to the pre-modern era. The second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, for instance, made more than 50 citations to a book called Meanderings of Memory. In the early 21st century, they realized that no one knew what Meanderings of Memory was, or whether it even existed. Further research turned up one more reference to it from Sotheby’s, but no trace of the text itself anywhere. It almost feels like cheating to put it on a list of poetical works that we’ll never read, but they think it must have been poetry. And, much the way we can't fully understand Aristotle without Margites, without Meanderings of Memory we will be forever incomplete in our lexical understanding of the words ‘cock-a-bondy,’ ‘couchward,’ ‘revirginize,’ and ‘vulgar.’

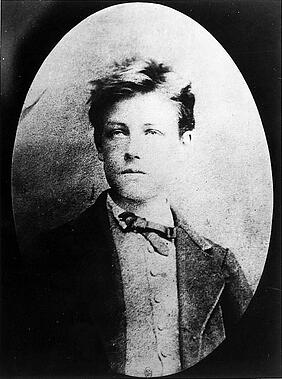

The Spiritual Hunt (1873)

In 1874, the wife of French poet Paul Verlaine could take no more of his extramarital affair with Arthur Rimbaud. She proceeded to burn all of Rimbaud’s “obscene and sexual” letters to Verlaine, along with what proved to be the only copy of The Spiritual Hunt, a prose poem that Verlaine would describe as Rimbaud’s “masterpiece.” Rimbaud stopped writing poetry at age 21 (after being shot in the wrist during a spat with his erstwhile lover Verlaine), and became an arms runner and quite possibly a slave trader, which makes the prospect of a lost masterpiece an especially enticing one—so enticing, in fact, that there was considerable literary uproar in 1949, when Pascal Pia presented what purported to be Rimbaud’s lost text to the French reading public. Unfortunately, by that summer the surrealist writer André Breton had outed the work as a forgery. Those of us who will never get to read Rimbaud’s last work might take comfort in these words by Edmund White: "in his overvaluation of this lost text, Verlaine seems clearly to have been what we might now call a drama queen; he couldn't remember a single line from it later, or even its title."

As My Brow Brushes On The Tunics Of Angels or The Drop Tower, the Roller Coaster, the Whirling Cups and other Instruments of Worship from the Post-Industrial Age (2114)

The most angst-inducing aspect of Borges’ "Library of Babel" may not be the possibility of lost texts, but the certainty of the infinite extant books that one will never be able to read in one’s lifetime. On that score, it seems like the creators of The Future Library project in Norway, which is gathering books from popular writers that it will keep under wraps and unread until 2114, are really just rubbing it in. In 2014, Margaret Atwood became the first contributor to the project with a work called Scribbler Moon (2114), which none of us will be alive to read. In 2015 her contribution was followed by a novella by David Mitchell, and in 2016 the Icelandic poet and Bjork-collaborator Sjón contributed a work called As My Brow Brushes On The Tunics Of Angels or The Drop Tower, the Roller Coaster, the Whirling Cups and other Instruments of Worship from the Post-Industrial Age, which, again, no one currently reading this will be alive to read when it’s published in a century.

Thank goodness there’s a world of poetry to keep us going until then.