India’s literature is just as vast and complex as the diverse, densely populated nation that produced it. Even if we limit ourselves to Indian literature written in English, we are still presented with a multicultural tapestry stretching back more than a century, from Rabindranath Tagore, who won India’s first Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913 for his “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful” poems and songs (eat your heart out Bob Dylan) to modern writers like Aravind Adiga (author of 2008’s Man Booker-winning debut The White Tiger). While one article can never encapsulate the entirety of an ever-growing canon, it can present a few names of writers from India that are indisputably worth knowing.

Salman Rushdie

Though the first Indian English novels were written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by writers like Raja Rao, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (who published Rajmohan's Wife in 1864), and R. K.Narayan (whose writing gained prominence in the West thanks to his lifelong friendship with Graham Greene), for many the elder statesman of the modern Indian novel in English is Salman Rushdie. While for some Rushdie’s name is more strongly associated with the fatwah issued for his death by the Ayatollah Khomeini, Rushdie’s novels are not to be trifled with. His epic, magical realist novels from Midnight’s Children (1981) to the The Satanic Verses (1988) to The Enchantress of Florence (2008) have earned him not just The Man Booker but the Booker of Bookers.

Though the first Indian English novels were written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by writers like Raja Rao, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (who published Rajmohan's Wife in 1864), and R. K.Narayan (whose writing gained prominence in the West thanks to his lifelong friendship with Graham Greene), for many the elder statesman of the modern Indian novel in English is Salman Rushdie. While for some Rushdie’s name is more strongly associated with the fatwah issued for his death by the Ayatollah Khomeini, Rushdie’s novels are not to be trifled with. His epic, magical realist novels from Midnight’s Children (1981) to the The Satanic Verses (1988) to The Enchantress of Florence (2008) have earned him not just The Man Booker but the Booker of Bookers.

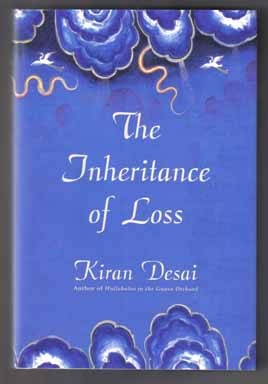

Kiran Desai

Rushdie’s rise to prominence would help pave the way for more Indian writers to achieve international acclaim. Nayantara Sahgal, a member of the Nehru-Gandhi family, quickly rose to prominence for her politically sweeping novels of the Indian elite, as did Anita Desai, who was thrice shortlisted for the Man Booker.

Rushdie’s rise to prominence would help pave the way for more Indian writers to achieve international acclaim. Nayantara Sahgal, a member of the Nehru-Gandhi family, quickly rose to prominence for her politically sweeping novels of the Indian elite, as did Anita Desai, who was thrice shortlisted for the Man Booker.

Anita Desai, for her part, very literally paved the way for one of the best modern Indian writers, her daughter, Kiran Desai. Desai’s 2006 novel The Inheritance of Loss, a post-colonial masterpiece of displacement and history, earned her the Man Booker Prize that proved so elusive to her mother.

Vikram Seth

Like Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth lives much of his time abroad (he owns and has restored the house of 17th century English poet George Herbert), and the argument could be made that the distance has sharpened his extremely keen eye for the often-tragic poetry of modern Indian life. His most famous book, A Suitable Boy (1993), has been compared to War and Peace (1869) and Middlemarch (1871), and not just because it clocks in at more than 1,300 pages. It takes aim at the caste system, local politics, and religious strife, and is based on an 18th century Chinese novel by Cao Xueqin. His other works include The Golden Gate (1986) and An Equal Music (1999), which, while perhaps less daunting, are equally delightful.

Arundhati Roy

The publication of Arundhati Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) has garnered her considerable media attention—with good reason: fans and critics have been waiting for a follow up to The God of Small Things (1997) for twenty years. A handful of detractors notwithstanding, the general consensus was not one of disappointment. In addition to her beloved (and Man Booker winning) debut novel, which is the highest selling book by an Indian author still living in India, Roy is also known for her political activism. She has written numerous works of non-fiction, ranging from defenses of Kashmiri independence to political opposition to neo-imperialism and nuclear proliferation.

Shashi Tharoor

Speaking of Indian novelists known for their political contributions: Shashi Tharoor is a Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha (the lower house of the Parliament of India), a former party spokesman for the Indian National Congress (a political party once led by Mahatma Gandhi), and a United Nations Under-Secretary General. He is also the author of The Great Indian Novel (1989), a widely acclaimed recapitulation of “The Mahabharata” (one of India’s national epics), in which political figures from India’s history are recast as mythological figures. The bitingly satirical take on India’s history is densely packed with allusions to other works about the country (like E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924)) and, of course, to the idea of the Great American Novel.