Though illustrations are today mostly synonymous with children’s literature, techniques for printing illustrations were developed and employed at almost the very moment the printing press entered use. And while contemporary publishers have a variety of methods at their disposal for mixing images and text, in the 15th century it was all about the woodcuts.

Woodcuts are made by carving images into wood blocks, leaving the areas to be printed level and cutting away the areas not meant to carry ink. Woodcuts were used in China for the creation of textile prints as early as the 3rd century A.D. While the art of woodcut printing was widely used in East Asia and was perfected over the course of the centuries, the technique didn’t make its way to Europe until the early 15th century, roughly the time at which paper had been introduced to that corner of the world. While woodcuts were initially used mainly to create cheaply reproducible artwork, their relevance to the world of moveable type would quickly become apparent. As both woodcuts and moveable type are relief-printed, they were natural bedfellows when the age of the printing press finally dawned.

Woodcuts are made by carving images into wood blocks, leaving the areas to be printed level and cutting away the areas not meant to carry ink. Woodcuts were used in China for the creation of textile prints as early as the 3rd century A.D. While the art of woodcut printing was widely used in East Asia and was perfected over the course of the centuries, the technique didn’t make its way to Europe until the early 15th century, roughly the time at which paper had been introduced to that corner of the world. While woodcuts were initially used mainly to create cheaply reproducible artwork, their relevance to the world of moveable type would quickly become apparent. As both woodcuts and moveable type are relief-printed, they were natural bedfellows when the age of the printing press finally dawned.

In the last quarter of the 15th century, woodcut illustrations entered a sort of golden age in Renaissance Italy. Though they initially gained widespread use in the printing of devotional aids (with different cuts being mixed and matched to combine certain common elements in depictions of saints), they quickly gained prominence as an artistic medium in their own right. Artists designed (though did not always actually carve themselves) spectacular illustrations that went into now-famed printings of works by Aesop, Boccaccio, and others.

Following their rise to prominence in Italy and Germany (where the technique was being put into use around the same time), woodcut illustrations would make their way to the United States in the late 17th century. John Foster, possibly America’s first maker of book illustrations, began using woodcuts in his Boston print shop as early as 1670. And though the style would lose prominence even in the United States by the end of the 18th century (owing both to the rise of copper plate engraving—a technique pioneered by Paul Revere—and to a decrease in the overall number of illustrations being printed in any given book), advances in technology would not spell the end for woodcut usage, owing to the creation of the Kelmscott Press.

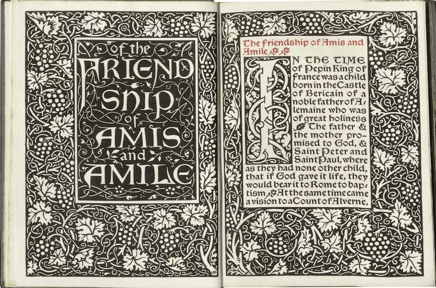

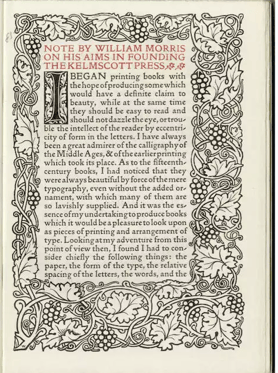

William Morris, an early fantasy author and socialist of the 19th century, believing strongly in the value of books as aesthetic objects in themselves, set out to create a series of beautifully illustrated volumes, most done with woodcuts. Drawing inspiration from his collection of 15th century German woodcuts, he founded the Kelmscott Press, which printed a number of his own works, in addition to works by Keats, Shelley, and Swinburne. The Press's crowning achievement, though, would be a much-sought-after printing of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

Even the era of the Kelmscott Press, however, would not prove to be the last word on woodcuts. Despite considerable advances in printing technology, woodcuts were still sometimes utilized (mostly in illustrated children’s books) in the 20th century for their aesthetic properties, being used in prints of works by Beatrix Potter, Marcia Brown, and Joyce Carol Oates.

Interested in viewing the woodcut process? Check out our collection of wood engraving videos.