"From the first, second, third, and fourth editions, all sound and sane expressions of opinion must be left out. There may be a market for that kind of wares a century from now. There is no hurry. Wait and see."

- Mark Twain, to his editors (1906)

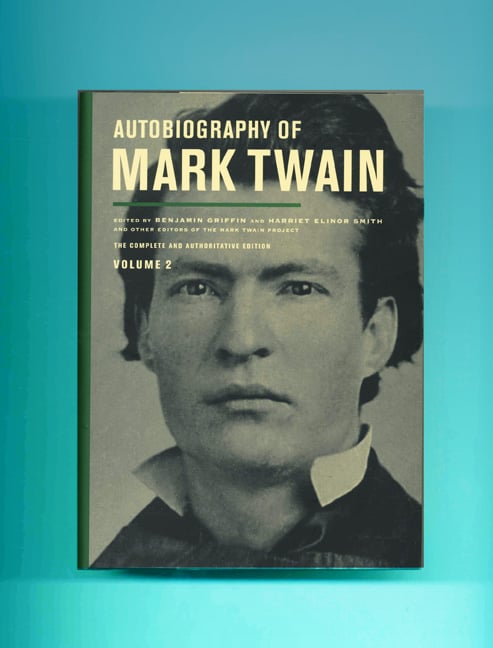

The much awaited second volume of The Autobiography of Mark Twain was released this week.. The autobiography offers a new--and often surprising--view of Mark Twain, often called the most American of American authors.

Although previous versions of Twain's autobiography have been published in the past, this edition is the first to present Twain's own words, uncensored, in the manner he intended.

Although previous versions of Twain's autobiography have been published in the past, this edition is the first to present Twain's own words, uncensored, in the manner he intended.

A Critically Acclaimed Edition

In November 2010, one hundred years after Twain's death, the University of California Press released the first volume of The Autobiography of Mark Twain. It was the first time that Twain's autobiography was presented in its entirety, in the manner that Twain dictated it to stenographers during his lifetime. The volume was wildly popular, spending several weeks at the top of the New York Times bestseller list.

Ron Powers, author of Mark Twain: A Life, noted in a phone interview with the Tmes, that prior to the release of this autobiography, Twain was "Colonel Sanders without the chicken, the avuncular man who told stories. He's been scrubbed and sanitized and his passion has kind of been forgotten in all these long decades. But here he is talking to us, without any filtering at all, and what comes through that we have lost is precisely that fierce, unceasing passion."

That authenticity and passion certainly come through because of the way Twain decided to undertake the composition of the work. He first attempted an autobiography in 1870 but kept putting the project aside. Then in 1904, he had an epiphany. He wrote to his friend William Dean Howells, "I've struck it! And I will give it away--to you. You will never know how much enjoyment you have lost until you get to dictating your autobiography." He called this method the "Final (and Right) Plan" for completing his autobiography. So over the course of four years, Twain dictated his autobiography to a stenographer. He made no effort to put events in chronological order or to censure himself. He also preferred the natural, frank tone that he could use when speaking instead of writing.

Censorship to Protect Twain's Reputation

Prior editions of Twain's autobiography had certainly been published before. Twain actually published "Chapters from My Autobiography in 25 installments in North American Review (1906-1907). But Twain clearly intended that the complete, unexpurgated work would not be published until long after his death. Indeed Twain noted in his 1899 outline of the project that the autobiography would be published either 100 years from 1899, or 100 years from his death. Twain even called his preface to the book "From the Grave."

Twain's friend, literary executor, and editor Albert Bigelow Paine followed Twain's instructions perhaps too faithfully; Paine's 1924 edition of the autobiography consisted only of 22 fragments, in the order that Twain composed them, including the first four months of Twain's dictations. It received relatively poor reviews, probably because it was overly sanitized. Paine steadfastly respected the wishes of Twain's daughter Clara that her father's reputation be protected, so he omitted anything that might have been remotely objectionable.

Twain's friend, literary executor, and editor Albert Bigelow Paine followed Twain's instructions perhaps too faithfully; Paine's 1924 edition of the autobiography consisted only of 22 fragments, in the order that Twain composed them, including the first four months of Twain's dictations. It received relatively poor reviews, probably because it was overly sanitized. Paine steadfastly respected the wishes of Twain's daughter Clara that her father's reputation be protected, so he omitted anything that might have been remotely objectionable.

Robert Hirst, curator and general editor of the Mark Twain Papers and Project at University of California Berkeley's Bancroft Library, notes that even in Paine's day his editorial style was draconian. "Paine was a Victorian editor," Hirst told the Times, "He had an exaggerated sense of how dangerous some of Twain's statements were going to be, which can extend to anything: politics, sexuality, the Bible, anything that's just a little too radical. This goes on for a good long time, a protective attitude that's very harmful."

Paine's successors weren't much more successful in accurately representing the legendary author. In 1940 historian and editor Bernard de Voto undertook a new edition called Mark Twain in Eruption. De Voto edited Twain's words and punctuation with a heavy hand and arranged the work by topic, destroying Twain's winsome order. And Charles Neider's 1959 version actually defied Twain's wishes completely; Neider arranged Twain's stories into chronological order, which Twain had specifically and enthusiastically avoided.

Paine's successors weren't much more successful in accurately representing the legendary author. In 1940 historian and editor Bernard de Voto undertook a new edition called Mark Twain in Eruption. De Voto edited Twain's words and punctuation with a heavy hand and arranged the work by topic, destroying Twain's winsome order. And Charles Neider's 1959 version actually defied Twain's wishes completely; Neider arranged Twain's stories into chronological order, which Twain had specifically and enthusiastically avoided.

A Wealth of Previously Unpublished Material

Admirers and collectors of Twain's work have enthuasiasticaly awaited the autobiography's publication because it paints a new picture of the author. Twain was outspoken in matters of politics, economy, and religion (to mention a few topics), but the autobiography is much more frank, honest, and comprehensive than anything most have read about Twain. Though Volume One of the autobiography was only about 5% unpublished material, Volumes Two and Three will contain much more previously unpublished material. By the time all three volumes have been published, scholars estimate that a full 50% of the autobiography will never have been in print before.

Twain takes no prisoners in his criticism of the military, the government, and even Wall Street Tycoons. He refers to American soldiers as "uniformed assassins" and heaps insults on plenty of now-obscure figures, like his publishers, lawyer, and even the inventor of a failed typesetting machine whom Twain felt had swindled him. He issues a particularly creative string of invectives against the countess who owned a Florence villa where Twain once vacationed with his family. Twain's frequently acerbic tone will certainly prove shocking for some who viewed Twain as a sort of benevolent author of charming classics--not an uncommon misunderstanding of the author.

But Twain, perhaps unsurprisingly, doesn't engage in much criticism of contemporary authors. He does note that Bret Harte is "always bright but never brilliant" and offers a sympathetic portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe in decline. But for Twain's criticism of other writers (most notably George Eliot and Henry James), readers will have to go to Twain's correspondence. This is likely due to Twain's general opinion of criticism: "I believe that the trade of critic, in literature, music, and the drama, is the most degraded of all trades, and that it has no real value....It is the will of God that we must have critics, and missionaries, and Congressmen, and humorists, and we must bear the burden."

If you'd like to be among the first to receive Volume Two of The Autobiography of Mark Twain, we have First Printings of the First Edition available. Miss Volume One? Get both volumes at once!