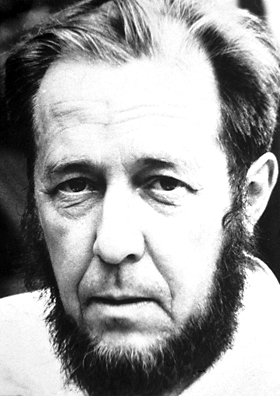

It would be an understatement to say that Russian writer Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn had a complicated relationship with his motherland. Despite suffering constant persecution during his adult life, Solzhenitsyn remained faithful to his culture, language, and countrymen. He revealed the cruel reality of the Soviet system to the world in both his fiction and his memoirs, for which he received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature. The world applauded him; the USSR tried to ruin him.

Solzhenitsyn was born into hardship. His father was killed in a hunting accident before he was born, which left his mother and aunt to care for young Aleksandr. During World War II, he served as a commander in the Red Army and spent time fighting on the front. As a soldier, Solzhenitsyn began to have doubts about the moral foundations of the government under Joseph Stalin, which he confided in private letters to a friend. Though they wrote in the vaguest of terms, his letters were intercepted and Solzhenitsyn was arrested in February 1945 for anti-Soviet propaganda. He was sentenced to eight years in a labor camp.

Because he had studied mathematics before the war, Solzhenitsyn was assigned to “special camps” for half of his imprisonment. He believed this is what kept him alive through the experience. He also began writing.

At the end of the sentence, he was informed that he would not be released, but was now exiled for life to Kok-Terek in what is now southern Kazakhstan. To top it all off, Solzhenitsyn soon grew gravely ill from cancer and had to be treated in a Soviet cancer hospital. In exile, he was allowed to teach mathematics and write in his spare time. The worry that no one would ever read his work weighed heavily on Solzhenitsyn.

In 1956, during what is called the Khrushchev Thaw (a period of de-Stalinization under Nikita Khrushchev), Solzhenitsyn was finally released and exonerated. In a potentially disastrous move, he submitted his work for official publication. Luckily, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was approved by the censors and was immediately popular both in the USSR and elsewhere. The book was even taught in Soviet classrooms.

The political climate had shifted by 1964, and Solzhenitsyn’s controversial writing was perceived as a threat. Solzhenitsyn was working on his magnum opus, The Gulag Archipelago, in secret. The three-volume narrative history of the Soviet prison system took him almost ten years to write, and the typewritten manuscript was hidden by friends at great personal risk.

The KGB and Soviet government continued to plague Solzhenitsyn; they attempted to discredit and even assassinate him. Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970, but he was unable to accept the award in Stockholm for fear that he would not be allowed to return to the USSR. Around this time, Solzhenitsyn wrote a private letter to leaders in the Kremlin about the challenges facing the USSR in coming years. It was publicly published as Letter to the Soviet Leaders. Even when he was painfully aware of his political unpopularity, Solzhenitsyn cared deeply about his homeland and acted to save it despite endangering himself.

The Gulag Archipelago was finally published by a French publisher in December 1973. Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported just six weeks later.

During his 16-year exile, Solzhenitsyn continued to protest the injustices he saw in the USSR (as well as the corrupting power of Western pop music). After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989-1991, Solzhenitsyn regained his Russian citizenship and was allowed to return. He died in 2008 at the age of 89, leaving behind an important literary legacy and an inspiring example of one man's fight against oppression.