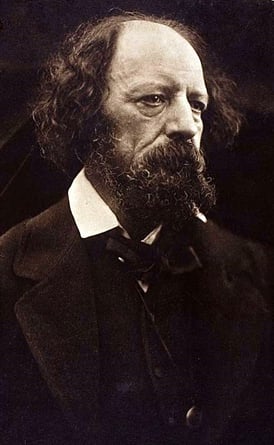

Alfred, Lord Tennyson remains the Oxford English Dictionary’s ninth most-quoted individual, and to look at his CV is to understand why. Named Poet Laureate of Great Britain upon the death of William Wordsworth in 1850, Tennyson’s poems have left an indelible mark not just on poetry but on the English language as a whole. “Tis better to have loved and lost/Than never to have loved at all,” entered (and remained in) the lexicon by way of Tennyson’s masterpiece In Memoriam A.H.H. (1849), while “Theirs not to reason why, /Theirs but to do and die” comes to us from “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (1854), one of the author’s most enduring works. A list of said works also boasts “Break, Break, Break” (1842), Idylls of the King (1859), and “Ulysses” (1842). For all that, however, the great ode-smith’s favorite of his own works was always Maud (1855).

Tennyson was born to middle class parents in Somersby, Lincolnshire in 1809. His childhood coincided with the careers of the great romantic poets like Keats, Wordsworth, and Coleridge—each of whom would leave an imprint on the young writer’s poetic imagination, seemingly nudging him toward what would become his most deeply explored subject: grief. At Cambridge he published his first volume of poetry, Poems Chiefly Lyrical (1830), to mild, mixed attention. Before taking his degree, he was forced by the death of his father to return home, whereupon he composed and wrote his second collection, which was largely derided.

Tennyson was born to middle class parents in Somersby, Lincolnshire in 1809. His childhood coincided with the careers of the great romantic poets like Keats, Wordsworth, and Coleridge—each of whom would leave an imprint on the young writer’s poetic imagination, seemingly nudging him toward what would become his most deeply explored subject: grief. At Cambridge he published his first volume of poetry, Poems Chiefly Lyrical (1830), to mild, mixed attention. Before taking his degree, he was forced by the death of his father to return home, whereupon he composed and wrote his second collection, which was largely derided.

Though his second foray into the world of publishing kept him from releasing any of his poems for a while, Tennyson did not stop writing. After the death of his friend Arthur Henry Hallam (who died of a stroke at age 22), Tennyson penned his best known elegy, In Memoriam A.H.H. Published as the poet’s fourth book in 1850, In Memoriam catapulted him to literary stardom. It caught the attention of Prince Albert, who arranged for him to receive the title of Poet Laureate that same year. And though she was not the primary proponent of his reaching his new post, Queen Victoria read the work and found it, years later, to be deeply comforting in the wake of Prince Albert’s death.

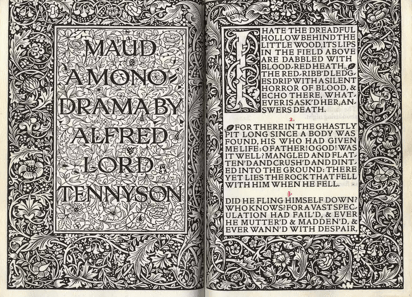

From there, Tennyson kept churning out hits. 1855 saw the publication of his first collection as poet laureate, Maud and other poems (1854). Though the collection is best remembered for having contained “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” which chronicles an ill-advised troop maneuver during the Crimean War, it is also notable for having contained Maud, a Monodrama.

Unarguably the centerpiece of the book, Maud deals with the doomed romance of its speaker and the titular Maud. The speaker, reeling from the death of his father, begins to court Maud only to find himself in a heated dispute with her brother. The speaker and Maud’s brother duel, and the latter is killed, forcing the speaker to flee to France and Maud to die (ostensibly) of a broken heart. Ultimately, the speaker, who has been in rather a manic state throughout, regains some of his wits and ships off to the Crimean War. Throughout Tennyson’s life, it remained his favorite of his own poems, and he was known to recite the whole text from memory at parties with little to no prompting.

In 1883, after multiple previous offers, Tennyson relented and agreed to be made a baron and thereby become the first poet to be elevated to the peerage solely on the strength of his or her work. Though Tennyson was often uncomfortable in his position as a peer, it’s hard to blame those who pushed it on him. The man gave so much to the English language, it was only appropriate that something substantial be given in return.