Sometime around Thanksgiving 1862, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), met sitting-president Abraham Lincoln. Upon the initial introduction, Lincoln famously quipped, “So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” Accounts of the exact wording vary, and in fact the whole story may be apocryphal, but it still speaks to the way that art and media help us make sense of history as it unfolds around us. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (or, if not Stowe’s novel, then perhaps works like Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1961) or 1845's The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass) gave 19th century readers new ways of understanding the “peculiar institution” over which the Civil War would be fought. As the war progressed, books like these continued to act as touchstones for anyone seeking to understand the conflict, the nation, and the world.

Art and Media as Touchstones

Today, we obviously do much the same thing. We use the Avengers movies to understand climate change, or the Star Wars sequels to understand political resistance. When we’re feeling bookish, Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (2009) might keep us moored as we think about power and the abuse or corruption thereof. Likewise, Philip K. Dick and George Orwell continue to inform our collective understanding of new technology as it emerges. Literary gods willing, one day the final A Song of Ice and Fire books will help inform our understanding of what went wrong in the Game of Thrones TV show.

Without these cultural touchstones to fall back on, modern life would be even more bewildering than it already is.

At the same time, our cultural referents sometimes change so quickly that it can be difficult to understand what previous generations might have been thinking. To understand the feelings that attended, say, VJ Day, we don't just need to understand WWII itself, we need to simultaneously strip away everything that’s emerged in the meantime. No one had a Kurt Vonnegut quote at the ready; no one flashed back to their first viewing of Bridge on the River Kwai.

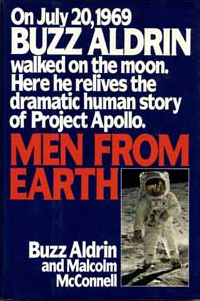

If you were to set out to write a list of the most notable moments in human history, leaving off the Apollo 11 mission—the first time a human set foot on the lunar surface–would rightfully raise a certain number of eyebrows. In some ways, though, understanding how the moon landing would have felt (even remembering how it felt, for those of you who were alive and cognizant) can be difficult. Years of elaborately shot and staged science fiction on film and television has, perhaps, made us a little bit jaded—the real thing is a touch grainy, a little retro by comparison. Many of us have read Andy Weir’s The Martian (2011), so if and when we daydream about space exploration we basically inhabit the mind of Robinson Crusoe, rather than a seasoned fighter pilot like Buzz Aldrin hurtling into the darkness.

Popular Fiction and Non-Fiction Books in 1969

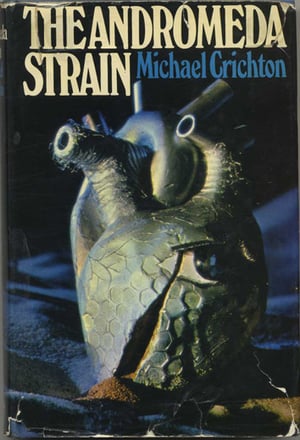

So, watching Apollo 11 take off, you wouldn’t have read The Martian or seen Star Wars (1977). But what would you have seen and read? What was the populace reading and watching at this critical moment in humanity’s history, and how might it have impacted our understanding of the event? Number one on the New York Times best seller list the week of the moon landing was The Love Machine (1969), Jaqueline Susann’s follow up to Valley of the Dolls (1966). Clocking in at numbers two and three were Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) and Mario Puzo’s The Godfather (1969), respectively. Next up was Nabokov’s Ada, or Ardor (1969), then Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain (1969), followed by Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-5 (1969).

For my money, it’s these last two that would have had the biggest potential impact on the average moon-watcher’s psyche. Crichton’s novel, which details the discovery of an extraterrestrial microbe that spreads a deadly infection upon its initial contact with humans, speaks not just to the fundamentally uncertain nature of space exploration as an undertaking, but also to the deep paranoia that rightfully infected any Cold War enterprise, no matter how inspiring. Slaughterhouse-5’s extraterrestrials, on the other hand, see all of time at once, serenely walking us right to the limits of human understanding. Billy Pilgrim (who famously “comes unstuck in time” at the novel’s outset) is mostly a lacuna where a space-faring protagonist should be.

On the non-fiction best seller charts, we find The Peter Principal (1969) reigning at number one. In it, Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull explain why, in many corporate and organizational structures, people tend to “rise to the level of their incompetence.” In case you felt like you needed an ironic lens through which to view the moon landing, that should pretty much suffice.

Box Office Hits Surrounding the Lunar Landing

If the literary landscape in June of 1969 was, by turns, somberly reflective and slightly hysterical, things at the box office were a little bit different. Modern viewers have a decade of Marvel movies under their belts, but that’s nothing compared to the steady stream of Westerns that greeted moviegoers throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s. By the late ‘60s, the standard studio Western was giving way to alternative takes on the genre (though “alternative takes” on the Western are as old as the Western itself), leading True Grit (1969, based on the novel by Charles Portis, to be adapted again more than 40 years later by the Coen brothers), Easy Rider (1969), and Midnight Cowboy (1969) to float towards the top of the charts. The latter two movies are, of course, not strict Westerns, but they certainly play on the genre’s ideology and iconography.

Again, you might be led to a somewhat dour view of American expansionism by what you were watching in the months leading up to the big event. The “Final Frontier,” insofar as it resembled any of the old frontiers, might have been a place of deep moral ambivalence. On some level, this might help explain the fact that the original Star Trek series was cancelled just a month before Apollo 11.

The Italian Job (1969) would round out the highest grossing films for the first half of the year, but all of them would be blown out of the water by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid upon its release in September of that year. If Easy Rider represented a kind of suspicious melancholy in the months leading up to the moon landing, Butch Cassidy might be seen as something like a victory lap—a star-laden, big budget ode to spectacle and anti-heroics. Neil Armstrong and his ilk were hardly outlaws, but perhaps the sheer audacity of the accomplishment made antiheroes palatable again. In some ways, it seems like the perfect antidote to something like Slaughterhouse-5, whose Weltschmerz seems to stretch out to infinity.