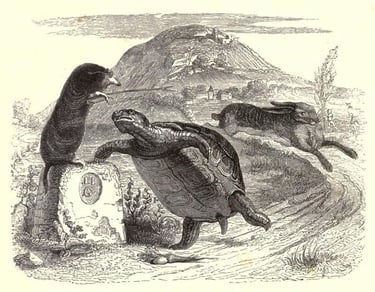

The genesis of the fable is unclear, but its legacy is far-reaching. The name "Aesop" is synonymous with fables, although the stories themselves and their corresponding lessons had been handed down for generations before he recorded them several hundred years B.C. They made their first appearance in printed English in 1484. It is safe to say, then, that fables are an integral part of our collective literary and cultural history. Their lessons are universal and timeless. Who among us has not been exhorted to heed the lesson of the Hare and the Tortoise and remember that “slow and steady wins the race,” or to mistrust appearances and beware of “the wolf in sheep’s clothing.” These morals were just one component of the fable formula, and they happened to be the component that Arnold Lobel disliked.

Fable Formula

Fable Formula

According to the Tales with Morals website, which lists and links to the text of a number of Aesop's fables, a fable. . .

- is a short story that teaches a lesson.

- includes animal characters who act and talk like people (one might think of them as lessons with “tails”).

- are often entertaining for kids of all ages.

- pass into our culture as a way to teach morals.

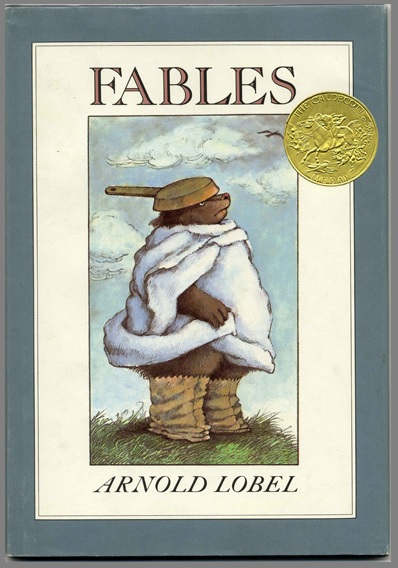

The Lobel Formula

It was this last component—the moralistic tone of fables—that Arnold Lobel disliked. As a talented writer and illustrator, he had been asked to create a new edition of Aesop’s Fables. The project was a non-starter for him, but it did plant the seed for a book idea of his own. He set out to write a new book of fables utilizing the original format but incorporating a lighter tone. Compiled in his book, Fables, each one page story was then paired with a detailed and delightful illustration. The Camel Dance features a camel in a tutu who, after a disappointing review, teaches us that “satisfaction will come to those who please themselves.” In The Ostrich in Love, a dapper, bow-tied ostrich reminds us when his love is unrequited, that “love can be its own reward.” These life lessons feel less like instructions and more like ways of coming to terms with our circumstances and finding joy in the journey.

The Lobel Legacy

According to an article from Parents' Choice, “Lobel called himself a daydreamer instead of an author or artist.” He naturally thought in pictures and was a master of the art of silly—never carrying it too far. Arnold Lobel loved what he did and said he could not think of any other work that “could be more agreeable and fun than making books for children”. This passion resulted in over sixty bestselling, award-winning books including Fables, winner of the 1981 Caldecott Medal for Illustrations. Lobel, who was also a poet, wrote the following lines: “Books to the ceiling/ Books to the sky/ My pile of books are a mile high.”

According to an article from Parents' Choice, “Lobel called himself a daydreamer instead of an author or artist.” He naturally thought in pictures and was a master of the art of silly—never carrying it too far. Arnold Lobel loved what he did and said he could not think of any other work that “could be more agreeable and fun than making books for children”. This passion resulted in over sixty bestselling, award-winning books including Fables, winner of the 1981 Caldecott Medal for Illustrations. Lobel, who was also a poet, wrote the following lines: “Books to the ceiling/ Books to the sky/ My pile of books are a mile high.”

As an author and illustrator, his pile of books certainly reached to a staggering height. If you are a collector of books or an avid reader (especially to children), make sure Fables by Arnold Lobel makes an appearance in your pile of books, preferably somewhere near the top.

That’s the moral of this story.

Sources: Tales with Morals, Carol Hurst, Parents' Choice