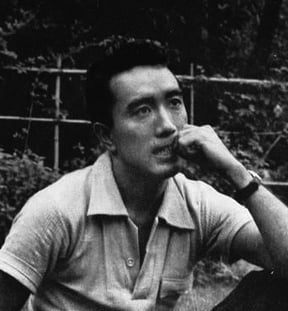

Yukio Mishima holds a prominent place in Japan’s rich literary history. Nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mishima's works explore ideas of sexuality, death, suicide, politics, Buddhism, Shintoism, atheism, innocence, corruption and aging to name a few. His Confessions of a Mask follows a young boy who realizes he is homosexual, and Mishima uses the boy’s internal monologue to explore what it’s like growing up gay in the conservative military society that was Japan before and during World War II.

Many posit that Confessions of a Mask was semi-autobiographical. Yukio Mishima’s own sexuality has been a matter of contention since his death. Mishima’s wife and children have long maintained that he was straight, but Mishima’s fellow writer and lover Jiro Fukushima recently wrote a book detailing his and Mishima’s relationship, much to the ire of Mishima’s surviving family.

Many posit that Confessions of a Mask was semi-autobiographical. Yukio Mishima’s own sexuality has been a matter of contention since his death. Mishima’s wife and children have long maintained that he was straight, but Mishima’s fellow writer and lover Jiro Fukushima recently wrote a book detailing his and Mishima’s relationship, much to the ire of Mishima’s surviving family.

Not only did Mishima’s sexuality flout conventional notions of gender roles, but Mishima’s politics also defied the typical dogmas of liberals and conservatives in post war Japan. Mishima’s beliefs were completely rejected by liberals in Japan because of his nationalism and his belief in Bushido—the samurai honor code. However, he didn’t fit in with conservatives, not only because of his aforementioned sexuality, but also because he argued that the Japanese emperor Hirohito should have stepped down when Japan lost the war.

Mishima wasn’t satisfied with being resigned to the quiet inaction of literary revolutionaries who let their work speak for them. He dreamed of igniting a revolution in Japan, and in 1970 he attempted to stage a coup d'état. Mishima was disheartened by the lack of action of students and liberals who admired people like Che Guevara but didn’t attempt to enact any change in the government. Mishima took it in his own hands to try and change the country.

Using his position in the military he, along with a small group of followers, visited the General of Japan’s Eastern Command. Barricading themselves in the General’s office, Mishima forced the General to call the soldiers into the courtyard below. From the balcony Mishima attempted to give a speech meant to inspire a coup, but instead he was laughed at by the soldiers. Returning to the office Mishima committed seppuku and ended his life in a grisly, violent fashion.

Using his position in the military he, along with a small group of followers, visited the General of Japan’s Eastern Command. Barricading themselves in the General’s office, Mishima forced the General to call the soldiers into the courtyard below. From the balcony Mishima attempted to give a speech meant to inspire a coup, but instead he was laughed at by the soldiers. Returning to the office Mishima committed seppuku and ended his life in a grisly, violent fashion.

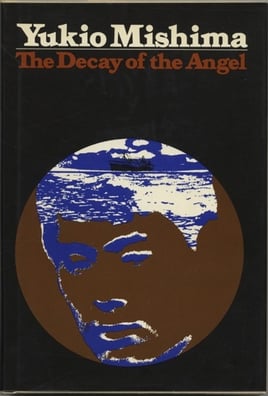

Mishima was not even 50 years old when he committed suicide. One has to wonder what other works the prolific author could have produce had he not cut his own life short. However, he remains one of the most important figures—if not the most important figure—in Japanese letters from the twentieth century.