Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail, who were good little bunnies, went down the lane to gather blackberries. But Peter, who was very naughty ran straight away to Mr. McGregor's garden, and squeezed under the gate!

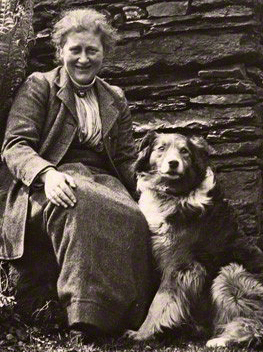

Like the mischievous, furry, little protagonist who propelled her into a wildly successful publishing career about as fast as he was able to get himself into trouble in Mr. McGregor's garden, Beatrix Potter had a rebellious streak a mile wide. Although she has become a household name as the author of enchanting children's stories, both her stories and her vocation ran much deeper. A constant disappointment to her parents because of her independence and refusal to adhere to the precepts of a privileged woman of Victorian society, Potter's stories are filled with spirited critters who are constantly breaking the rules laid down for them. Had Potter been the proper Victorian daughter her parents craved, she would have focused all her energies on social standing and making an advantageous marriage. Rather, determined to do something with her life, she passionately and rebelliously poured herself into pursuits in science, publishing, and conservation.

Born into an affluent family in 1866, Helen Beatrix Potter was raised in Kensington, London at 2 Bolton Gardens. Her parents had made enormous efforts to climb the social ladder and live down their roots in trade as the descendants of wealthy cotton manufacturers. Potter was homeschooled by her governesses. Her pets took the place of school friends, and she spent hours observing and sketching them. This activity evolved into a love of and aptitude for natural history, science, and art. In the summers, Potter's father rented a country house in which the family vacationed for three months. During her earlier years, the Potters spent their summers in Scotland, but they began to summer in the Lake District as she grew older. On these holidays, she rambled the countryside studying plants and animals.

Born into an affluent family in 1866, Helen Beatrix Potter was raised in Kensington, London at 2 Bolton Gardens. Her parents had made enormous efforts to climb the social ladder and live down their roots in trade as the descendants of wealthy cotton manufacturers. Potter was homeschooled by her governesses. Her pets took the place of school friends, and she spent hours observing and sketching them. This activity evolved into a love of and aptitude for natural history, science, and art. In the summers, Potter's father rented a country house in which the family vacationed for three months. During her earlier years, the Potters spent their summers in Scotland, but they began to summer in the Lake District as she grew older. On these holidays, she rambled the countryside studying plants and animals.

Beatrix Potter the Scientist

Biographer Linda Lear, author of Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature writes:

"Her artistic skills and imagination drew her to a fascination with fungi. Encouraged in her efforts at scientific illustration by a reclusive Scottish naturalist, Beatrix accurately painted hundreds of specimens, and drew many under the microscope. In advance of her time, and flaunting the prohibitions against women in science, she proposed a theory of germination in 1897 and argued in vain for the existence of cellular symbiosis."

In a 2006 article for The Telegraph, Louise Carpenter writes of Potter, "Even in the animal drawings Potter made as a child there is an attention to physical form, attained through her habit of boiling her dead rabbits down to their carcasses so she could study their skeletons."

Beatrix Potter the Author

It seems she was a woman far better suited to a modern biology lab than the drawing rooms of Victorian London, and much to the chagrin of her parents, Potter's capabilities didn't stop there. The story of Peter Rabbit was first written in 1883 as an illustrated letter sent to young Noel Moore, the child of a former governess. After having some of her artwork published in the form of greetings cards, Potter decided to develop Peter Rabbit's story into a picture book.

At first she couldn't find a publisher for it, so she self-published the story and gave it out as a gift to friends and family. As word spread about what she called her "little book," she began to receive requests for it from bookstores. Finally, Norman Warne of Frederick Warne & Co., a publishing company that had previously rejected her, took an interest in the growing popularity of the picture book. It was published in 1902 as The Tale of Peter Rabbit. It cost one shilling in stores, and became an immediate bestseller; the first printing sold out before the book was even published. Potter would go on to publish two books a year with Frederick Warne & Co. for the next eight years and would continue to publish with them until 1930.

Beatrix Potter: A Tale of Heartbreak

Louise Carpenter, in her 2006 article, writes:

"It is easy for those unfamiliar with her work to write it off as sentimental. Potter's world is inhabited by, among others, a bunny in a blue coat with brass buttons and a daft white duck in a bonnet and shawl. And yet embedded in this childish innocence is an acute, adult understanding of life's dangers and cruelties. Various creatures end up in pies, for example, the silly, unsuspecting Jemima Puddle-Duck is about to get eaten by a fox, the flopsy bunnies get thrown in a sack ready for Mr. McGregor's supper and Pig-Wig is destined to become bacon."

For Beatrix Potter, one of her life's greatest cruelties befell her in 1905 when a secret love affair ended in tragedy. She was well into spinsterhood at the age of 39 when her editor, Norman Warne proposed on June 25. The years of creative collaboration had been fertile ground for love to grow between the two.

Potter's parents were horrified. They had spent too much energy trying to erase their past connection to trade for their daughter to marry a tradesman. They opposed the marriage, but Potter accepted Warne's proposal anyway. However, in deference to her parents, she agreed to keep her engagement a secret while on the family's traditional summer holiday in the Lake District. Sadly, the engagement lasted no longer than five weeks. While Potter was away from London, Norman Warne became sick and died. Because the engagement had been secret, Potter would receive no condolences. Her relationship with Warne was seen as no more than a business connection, but she would wear his engagement ring for years to come.

Beatrix Potter the Farmer

Having earned some money from the sale of her books, Beatrix Potter purchased a little farm in the Lake District called Hill Top farm in the village of Near Sawrey. It was there she went to grieve Norman's death. She threw herself into her writing and turned to farming, as well, to assuage her loss. As the success of her books increased over the years, so did her income, which she used to purchase livestock. With the help of local solicitor, William Heelis, she also purchased more land around Near Sawrey. Her interest in farming increased tensions at home with her parents with whom she still lived full-time as was befitting of a dutiful Victorian spinster-daughter. However, she tried to get away to Hill Top farm as often and for as long as she could.

Having earned some money from the sale of her books, Beatrix Potter purchased a little farm in the Lake District called Hill Top farm in the village of Near Sawrey. It was there she went to grieve Norman's death. She threw herself into her writing and turned to farming, as well, to assuage her loss. As the success of her books increased over the years, so did her income, which she used to purchase livestock. With the help of local solicitor, William Heelis, she also purchased more land around Near Sawrey. Her interest in farming increased tensions at home with her parents with whom she still lived full-time as was befitting of a dutiful Victorian spinster-daughter. However, she tried to get away to Hill Top farm as often and for as long as she could.

After a few years, Potter was elected to the local landowner's association for whom Heelis served as legal advisor. By 1912, she had refocused most of her creative energy on farming rather than writing, and in June of that year William Heelis proposed. The two were married in August of 1913 when Potter was 47 years old. Finally, she was able to escape the tyranny of her parents, make Near Sawrey her permanent home, and farming her full-time vocation.

Beatrix Potter the Conservationist

After World War II, Potter became interested in conservation efforts and found a mentor in Hardwicke Rawnsley, founder of the National Trust, who was also her good friend. His influence drew both Potter and Heelis into a close partnership with the Trust. Not only did they want to preserve the land, but the culture of fell farming (hill farming) as well as the pure-bred Herdwick sheep that were part of that culture. Potter continued to buy land and farms in the area as they came on the market, and joined the Herdwick Sheep Breeders' Association. She was one of only a handful of female members.

Biographer Anne Lear writes:

"In 1929 her skill at managing Lakeland farms was tested when she seized the opportunity to buy and preserve Monk Coniston Park. A 4,000-acre property, its many component farms, straddled the Coniston and Tilberthwaite valleys, and included not only Tarn Hows, the large teardrop-shaped lake long famous for its scenic beauty, but also Holme Ground, a farm that had once belonged to Beatrix's great grandfather. The piecemeal purchase of Monk Coniston would have meant the disintegration of traditional hill-county farms, the loss of livelihood to farmers, tenants and cottagers, and the scattering of livestock, particularly Herdwick sheep."

Potter bought the property in partnership with the National Trust. The agreement between the two parties was that when the Trust had raised enough money, they would purchase half of the land back from Potter. Potter was so good at managing Monk Coniston that even after the Trust bought back their half of the land, they asked Potter to continue managing both properties. She was then 65 years old. When Beatrix Potter died in December of 1943, she left more than 4,000 acres to the National Trust.

As a young woman Beatrix Potter was determined to do something meaningful with her life; something outside of the parlors of Victorian England. She was a rebel with a cause. "If I have done anything -- even a little -- to help small children on the road to enjoy and appreciate honest, simple pleasure, I have done a bit of good," she once said. Beatrix Potter has done a "bit of good" for countless children the world over. Today, her books still sell in the millions and have been translated into thirty languages. In addition, she successfully preserved most of what is now Lake District National Park.