HIS golden locks Time hath to silver turnd;

O Time too swift, O swiftness never ceasing!

His youth gainst time and age hath ever spurnd,

But spurnd in vain; youth waneth by increasing:

Beauty, strength, youth, are flowers but fading seen;

Duty, faith, love, are roots, and ever green.

His helmet now shall make a hive for bees;

And, lovers sonnets turnd to holy psalms,

A man-at-arms must now serve on his knees,

And feed on prayers, which are Age his alms:

But though from court to cottage he depart,

His Saint is sure of his unspotted heart.

And when he saddest sits in homely cell,

Hell teach his swains this carol for a song,

Blest be the hearts that wish my sovereign well,

Curst be the souls that think her any wrong.

Goddess, allow this aged man his right

To be your beadsman now that was your knight.

--George Peele, "A Farewell to Arms"

Ernest Hemingway published A Farewell to Arms in 1929, and the novel met with instant success--it sold so well that it made Hemingway financially independent. A Farewell to Arms has endured as one of the greatest war novels in American literature.

Renaissance Roots

Hemingway took the title for A Farewell to Arms from the eponymous poem by George Peele, a sixteenth-century dramatist. Peele is also sometimes credited with having written parts of Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus--mainly because he had a predilection for violence in his writing. His violent tendencies seem discordant with the content of "A Farewell to Arms," however. Written to Queen Elizabeth, the sonnet is an apology for Peele's inability to continue fighting in the military for moral reasons.

Hemingway was not the first to evoke Peele's poem. William Makepeace Thackeray borrowed lines from the poem in his 1855 novel The Newcomes. Hemingway gave the poem new relevance, reminding us of the atrocities of modern warfare, which he himself had witnessed.

Hemingway was not the first to evoke Peele's poem. William Makepeace Thackeray borrowed lines from the poem in his 1855 novel The Newcomes. Hemingway gave the poem new relevance, reminding us of the atrocities of modern warfare, which he himself had witnessed.

Autobiographical Undertones

A Farewell to Arms is based on Hemingway's own experiences in Italy during the First World War. At eighteen, he was eager to serve in the military. But poor eyesight made that impossible, so he joined the ambulance corps. After a brief stint in France, Hemingway was transferred to Italy. He was the first American injured in Italy. A nurse who cared for him, Agnes von Kurowsky, inspired the character of Catherine Barkley. Kurowsky declined a relationship with Hemingway after he returned to the United States.

Hemingway's biographer Michael Reynolds calls A Farewell to Arms "the premier American war novel from that debacle [World War I]." But he also warns that even though the novel was certainly inspired by events in Hemingway's life, we must not read too much reality into the novel's pages; Hemingway was not personally involved in the battles recounted in the novel's pages.

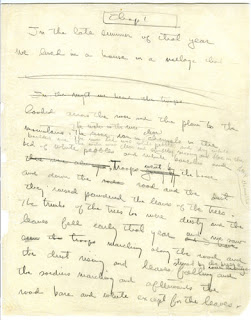

Controversial First Edition

Hemingway first published A Farewell to Arms serially in Scribners Magazine from May 1929 to October 1929. The book was published in September 1929, with a first run of about 31,000 copies. In the first editions, vulgar language is replaced with dashes. Hemingway personally added handwritten corrections to at least two copies. The first was for James Joyce, and the second went to Maurice Coindreau, who translated the novel into French.

The novel was not published in Italy until 1948 because its anti-military tone and depiction of the Battle of Caporetto were seen as unflattering to the armed forces of the Fascist regime. Fernanda Pivano wrote an illegal translation in 1943 and was subsequently arrested in Turin. She and Hemingway would eventually meet and collaborate closely.

Alternate Endings

Hemingway wrote the end of A Farewell to Arms while his wife was preparing to give birth to their child. He later admitted in a 1958 Paris Review interview that he'd changed the novel's ending around 37 times. Reviews of his manuscripts reveal that the number was really 47. The endings range from a few words to several paragraphs.

Hemingway wrote the end of A Farewell to Arms while his wife was preparing to give birth to their child. He later admitted in a 1958 Paris Review interview that he'd changed the novel's ending around 37 times. Reviews of his manuscripts reveal that the number was really 47. The endings range from a few words to several paragraphs.

Of all these endings, most critics agree that Hemingway chose the most appropriate for his seminal work.Since 1979 the manuscripts containing the alternate endings have been at the John F Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum (see photo at left) They offer a fascinating and inspiring glimpse into Hemingway's creative process, a privilege not often available.