When J.K. Rowling, author of the famous Harry Potter series, admitted that she wrote The Cuckoo's Calling under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, the world was in uproar. It should come as no surprise that Rowling would choose to write under a false name, though. After all, she originally hid her identity by writing as J.K. Rowling—rather than using her full name, Joanne Rowling—and she's not the first legendary author to use a pseudonym. On the contrary, Rowling is in terrific company! She used a pseudonym "for the joy of it," but authors' motives are quite varied. Here's a round-up of some famous authors and their better or lesser known pseudonyms.

On the contrary, Rowling is in terrific company! She used a pseudonym "for the joy of it," but authors' motives are quite varied. Here's a round-up of some famous authors and their better or lesser known pseudonyms.

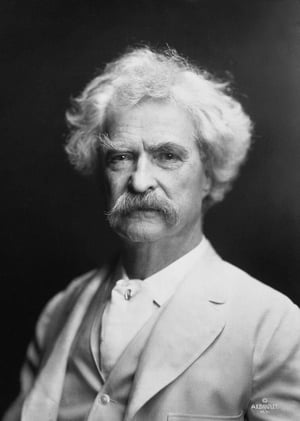

Mark Twain

Samuel Clemens grew up in Hannibal, Missouri. He eventually went to work for his older brother at the local paper, and it was there that he first used a pseudonym. When filling in for the editor, Clemens signed his article "W. Epaminondas Adrastus Perkins." Later he would also write under the names Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, Quintus Curtis Snodgrass, and others. He wasn't the only one publishing under false names; the self-important steamboat pilot Isaiah Sellers, who was published in the New Orleans paper, used the name "Mark Twain," and Clemens liked the way it sounded. By February 1863, Clemens thought that Sellers had passed away—and decided to appropriate his cognomen! He signed three letters to the Enterprise on the legislative session in Carson City as Mark Twain. He continued to publish under the name, and soon the original pseudonym owner was overshadowed by the new Mark Twain.

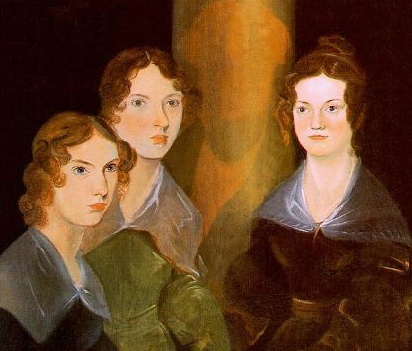

Anne, Charlotte, and Emily Bronte

The Bronte sisters originally published under the respective names Acton, Currer, and Ellis Bell. Their first book, which they published in May 1846 at their own expense, was a volume of poetry, and they feared that the book would be received less warmly if it was published by women. The sisters chose more gender-neutral names because they had misgivings about using outright masculine names. Anne wrote in her introduction to Wuthering Heights that "while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because—without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what was called "feminine"—we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice."

Charles Dickens

The "Inimitable" Charles Dickens launched his career anonymously. His first published piece appeared in The Monthly Magazine in December 1833. Entitled "Mr. Minns and His Cousins," the sketch bore no name. Dickens continued to publish anonymously until August 1834, when "The Boarding House" appeared with the signature "The Inimitable Boz." The epithet was an adaptation of Dickens' nickname for his younger brother Augustus. Dickens called him "Moses," after a character in Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. Pronounced through the nose, this name became "Boses," and was easily shortened to "Boz." The pseudonym proved quite the mystery, even inspiring verses in the March 1837 Bentley's Miscellany:

"Who the dickens 'Boz' could be

Puzzled many a learned elf

Till Time unveiled the mystery

And 'Boz' appeared as Dickens' self"

After Dickens was revealed to be "The Inimitable Boz," he dropped the "Boz" but continued to be known as "The Inimitable."

Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was a mathematical lecturer at Oxford University. The scholar was also interested in photography, religion, science...and storytelling. Dodgson took particular pleasure in weaving tales and making up puzzles for children. Before he published Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), he decided that he wanted to protect his privacy—a common practice among Victorian authors. He took the first two parts of his name and translated them into Latin, yielding Carolus Ludovicus. He reversed their order and translated them loosely back to English, yielding Lewis Carroll. The nom de guerre was one of several that Dodgson submitted to his publisher as possibilities. It was the publisher who actually selected Lewis Carroll. Dodgson guarded his privacy fiercely, even refusing letters addressed to his home that bore his pseudonym. But occasionally, to smooth introductions to children or members of high society, Dodgson would use his pen name.

Louisa May Alcott

Famous for writing the wholesome novel Little Women, Louisa May Alcott penned a much wider variety of works than most people realize. She started out writing under the pen name Flora Fairfield, largely because she wasn't sure she wanted to pursue a career in writing. In 1862, Alcott began using the name A.M. Barnard, and some of her melodramas were produced on the Boston stage under this name. It was in 1863, with her Hospital Sketches, that Alcott decided to devote herself to writing. Shortly thereafter, she began writing articles for The Atlantic Monthly and Ladies' Companion that bore her own name. But it wasn't until decades later that Alcott's secret identity was revealed. Using the pseudonym A.M. Barnard, Alcott had published a number of "blood and thunder" stories—both lurid and unbefitting to a lady—to pay her family's bills. Scholars Leona Rosenberg and Madeleine B. Stern were poring over Alcott's correspondence at Harvard University's Houghton Library when they encountered five letters from 1865 and 1866. The letters, from Alcott's Boston publisher James R Elliott, stated, "We would like more stories from you...and if you prefer you may use the pseudonym of A.M. Barnard or any other man's name if you will." The letters also outlined the stories Alcott had written under the name and the publications they appeared in.

Stay tuned for the second installment for more famous authors and their sometimes-unexepcted pseudonyms!