As an apprentice to the craft of binding and restoring rare books, the author discovered the sense of pride that comes from being part of a lineage stronger than blood and the responsibility of passing on that craft to the next heir.

By the time I reached the University of Oklahoma library, I was already thirty minutes late. I took the elevator to the fifth floor, using the time to quietly think of an acceptable excuse.

As the door opened, it occurred to me that no excuse would be necessary since I had a history of rarely being on time. I was not proud of this fact, but after five years, it was expected that I would be fashionably late. My normal routine was to arrive at the History of Science Collections, exchange the normal niceties with the staff, pick up the books needing repair and conservation, then make toward the door with the books in hand. But without fail my route to the door would be curtailed, and I would end up chatting for hours with the various waves of students and professors who came to loiter between classes. The collections were always teeming with students and professors posing their conspiracy theories about whether or not Kepler murdered Brahe, Newtons nontrinitarian views, and where Copernicuss remains were really stashed. Every visit was full of intrigue and spicy food for thought. Today, however, I headed straight back through the locked double doors to the workroom. Yes, today was strictly business, and I was already later than what was fashionable, even for me.

With eyes baggy and bloodshot from the sleepless night before, I nervously greeted the curator, Marilyn Ogilvie, and the rare books librarian, Kerry Magruder. Dr. Ogilvie motioned toward the vault. Shall we? she inquired. I nodded and we all solemnly filed into the vault as if we were in a funeral procession. Wait here and dont move while I punch in the security code, she whispered. I averted my eyes as she punched in the security code on the keypad so as to not see the code, a habit I still observe today. There is something almost holy about the idea of only two people having access to the code, and I felt it was in my best interest not to be one of them. With the security alarm deactivated, I looked up, and as I had so many times before, took a long deep breath of the vaults cool, humid air. The peppery smell of ancient leather was enticing and almost medicinal. Ogilvie and Magruder walked to the back of the vault and disappeared into the stacks, while I stood there in full sensory overload.

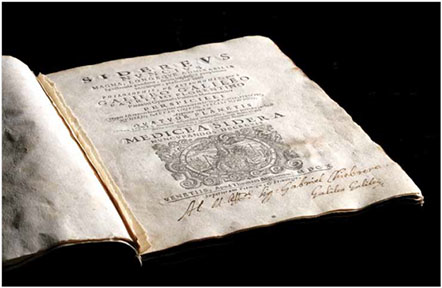

Here it is, echoed Marilyns voice from the stacks, and the two emerged with a thin little quarto in limp vellum. Its cover was supple, even after four hundred years. The mellow ivory-colored vellum was warm and inviting. Opening its cover, I caught a glimpse of an inscription. I paused, put my hand on my heart as if to keep it from pounding too loudly, and leaned in for a closer look. The writing was a bit faded, but its sienna color was still quite pronounced. It was in Italian and hard to discern, but the two final words were as clear as the summer sun: Galileo Galilei.

Amazing, I whispered, as if I were standing in the presence of the man himself. Authenticated by experts decades ago, the book was rumored to be worth more than $2 million. This was, after all, a rumor; no one ever dared to speak of monetary values in the collections. The books were referred to as rare, exceedingly rare, or irreplaceable. This copy of the Sidereus nuncius was irreplaceable, its condition dangerously fragile.

I was to perform the two weeks of conservation work in house due to the value of the piece and the liability involved in taking it from the confines of the library. The project was fairly simple, but the books obvious history and illustrious provenance would make this anything but a routine task. The book needed to be taken apart, cleaned, digitized, resewn, and recased in its original vellum binding.

I was to perform the two weeks of conservation work in house due to the value of the piece and the liability involved in taking it from the confines of the library. The project was fairly simple, but the books obvious history and illustrious provenance would make this anything but a routine task. The book needed to be taken apart, cleaned, digitized, resewn, and recased in its original vellum binding.

I spent the next day hauling pieces of equipment and tools to the makeshift conservation lab that was set up just steps away from the vault. Security was serious business during this time, and even though I had the full confidence and support of the staff, every detail of the project went by the book. My bags were checked every day upon entering and exiting the conservation area. I was amazed by the staffs diligence, but their efforts began to make me feel a bit self-conscious, and it wasnt long before the trepidation began to set in. Was I prepared for such a feat? I wondered. After all, I had worked on many books worth in excess of $100,000. My mind began to harbor the fantasies and feelings of inadequacy that anyone would have standing in the shadow of Galileo. Do this job flawlessly and youll gain respect, accolades, and a paycheck! I told myself. On the other hand, Screw this up, and you can take your thirty pieces of silver to the potters field. The stakes were high since the circle is very small at the top. Success or fail, word would travel and travel fast.

In reality I had very little to worry about. I had trained with some of the best, and, most important, I was about as anal retentive as a neurosurgeon operating on Einsteins brain. I rarely missed a detail, and my work was precise and painfully deliberatean odd skill set for someone who barely graduated high school. My parents always assumed I was intelligent enough but just didnt try. As a child I got lectured a lot about being lazy. But the truth of the matter lay in the fact that I was bored. That all changed for me in the fall of 1989, when two seemingly unrelated things occurred that would change my path forever.

At fourteen I was an odd child. I spent my time after school wading through creeks and rounding up crayfish or the occasional red-eared slider. Many days were spent in the country walking riverbeds, looking for fossils and artifacts. Weekends were for going antiquing with my parents. We would shop the same little stores that speckled the Kansas-Oklahoma borderlands week after week. It was during one of these little trips in November 1989 that I found my first antiquarian book, a 1790 printing of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. It had been haplessly thrown into a basket with a bunch of paperback Louis LAmour books and some tattered McGuffy readers.

It couldnt have been much more than a week later that an unexpected package arrived through the mail. In an odd and serendipitous succession of events, I was the mistaken recipient of a misplaced parcel, a catalog of rare books. The catalog was from Philip Pirages Rare Books. I was instantly infatuated with the hundreds of photos and descriptions of the bindings. I was quick to snatch up and pore over each catalog as it arrived and began replacing my riparian adventures with more refined pursuits.

I started buying early volumes from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, mostly books from misplaced sets. Like a bibliomaniacal Vesalius, I performed book autopsies, taking apart the tomes layer by layer, peeling back the volumes to reveal every aspect of their construction. I noted everything and began making models of the books I had disemboweled. Like Mary Shelleys Frankenstein, I delighted in bringing the books back to life. It wasnt enough just to craft a simple codex; the book had to be a living, breathing tome. Its sewing had to be identical to the original, and I tried my best to use authentic materials. In the beginning, the results were atrocious, and looking back, I wonder why I stuck with it.

Completely oblivious to the fact that the binders art was still alive and well in the rare-books market and elsewhere, I decided to go on with my life. I gained an undergraduate degree in psychology and pursued a masters degree in museum studies, all the while still feeling as if I were missing out on something very special. At the time, I was still receiving Piragess catalogs and binding books merely as a hobby. One day in December 1997, I decided to call him to add another two years to my subscription, which, although I offered payment for the cost and his trouble, he was gracious enough to keep sending at no additional charge. Our conversation was brief that day, but before hanging up, I inquired about the bookbinders craft. Was it still performed professionally? He eagerly exclaimed that it was, indeed, and that he used restoration binders frequently. He also mentioned that a good binder could make very nice wages. I realized then that I wanted to pursue the craft wholeheartedly.

I knew from my readings that the most common way of learning the art was to take up the arduous challenge of the apprenticeship, so I began researching the field. After a few months I was still unclear as to what an apprenticeship entailed, since most of my references were from the midnineteenth century. Was I to move in with a stoic old sage, be confined to menial servitude until I had attained some sort of enlightenment? Would I work for the archetypal Mr. Miaggi and perfect the esoteric philosophies surrounding the craft? Or inherit a bindery in the Swiss Alps after marrying the binders beautiful daughter, who had begun to harbor a secret and passionate love for me since I had arrived to work with her father? My imaginary ramblings were ridiculous, even laughable. I would come to realize how absurd my preconceptions about the apprenticeship tradition really were as I delved further into the truththe practice was quickly vanishing. I began to realize I would not be inheriting a bindery, and no one was marrying the binders daughter, especially me.

I was on my own and without a competent binder within a 500-mile radius. Just finding one at all was proving to be a difficult task. I found most bookbinders congenial but reluctant to share any details about their craft that might jeopardize their livelihood. One binder in Alabama invited me to work with him at his studio, luring me with his supposed insight into the craft and promising an Old World apprenticeship experience. It turned out to be just a chance for him to get some free help sorting type and sweeping the floors day after day. After uncomfortable meetings and hostile exchanges, I became quite discouraged about the matter.

Yes, I was on my own. I referred to my list of binders, checking each one off as I burned bridges. Completely running out of steam and doubting the value of my pursuit, I decided to structure my own apprenticeship. Diligently assigning myself reading assignments, projects, and technical exercises, I spent the next two years honing my budding skills. My skills were blooming, and I was turning out some very good work, but I lacked the mentoring I needed to learn the nuances and secrets of the craft. I also lacked the teachers reinforcing encouragement when I had mastered a new skill or the slap on the hand when I was doing it all wrong. I was getting paid for bindings now, but knew that soon I would need to study with someone to reach the next level I so desired.

Mr. Pirages, the one person I trusted as an authority on the subject, was quick to recommend Jan Sobota, who was known as a master in Europe and was living in the Czech Republic. I had seen his work in Piragess catalogs, and his name was a byword among book dealers and collectors. After several weeks of correspondence, Jan invited me to come over and begin my apprenticeship with him and his wife, Jarmilla, who is also an accomplished binder. My wife, Angela, who was born in Germany, and my one-year-old daughter were to go along. We traveled to Dresden, Germany, where we spent some time getting set up in an apartment on 29 Prellerstrasse. I promptly established contact with the conservation program at the Sächsische Landesbibliothek, where I would later study paper and vellum conservation. I was also given access to research their fine collection of Jacob Krause bindings and Martin Luther manuscripts.

The author (left)with mentor Jan Sobota

The author (left)with mentor Jan Sobota

Jan's bindery was on the first floor of a three story building that was built sometime in the thirteenth century. It was part of a string of buildings that circled a twelfth-century castle. The ceiling was spanned with beautiful arched vaults, and the walls were two feet thick. This was the perfect setting for learning the age-old craft. The walls of his shop were littered with shelves, and racks of every kind held tools for cutting, gilding, scoring, painting, and every conceivable utensil one could need.

Jan was exceedingly generous with me throughout my training, continually giving me books to read, tools, and materials. There was nothing he kept back, answering every question with direct honesty. We usually worked from seven to noon, ate lunch, and then Jan would take a nap. This gave me ample time to explore the castle, church, and the surrounding countryside. The castle was just across the lane on the crest of the hill. I spent many hours there watching the local archaeologists unearth Roman graves from the bowels of the castle. Work would resume around two, and we would work late, often until dinner was ready. This does not include the many unscheduled breaks we took in the large closet at the back of the bindery, where we would sneak treats from Jans secret stash of holiday cookies and drink his favorite Becherovka, an herbal liquor only made in neighboring Karlovy Vary. It was during these breaks that he would tell me stories of his youth and his apprenticeship with Karel Silinger. He also told me of his tragic experiences with the secret police in the 1960s and about the years he spent on the run and seeking political asylum in the 1980s. Through his many stories, Jan impressed in me the sense of pride one must have in ones work and in his lineage as a craftsman. He taught me to never forget the forefathers of the craft and those from whom we learned. Jan impressed upon me that his teacher Karel and his teacher before him had become part of my lineage as a binder as well. A part of them lives on in me through my skills and techniques.

When I left for home in January 2003 to do work for the University of Oklahomas History of Science Collections, I carried back the tools, materials, and books Jan had given me over the course of my studies. I also brought back the sense of pride that comes from being part of a lineage stronger than blood and the responsibility of passing on that craft to the next heir.

After about two weeks, the work was finally finished on the Sidereus nuncius. The job had been a difficult oneit challenged me in ways I would not have expected. The amount of publicity was amazing. During the course of the two-week project, the area had been full of interested people hoping to catch a glimpse of the bookbinder in his natural environment. It was all I could do sometimes just to keep focused on the task at hand. Today was the last day of work on the Sidereus nuncius, and the local news crew had just finished filming the final steps in the books restoration and were packing up to leave. It was especially refreshing to be done and off camera. As I sat there looking at my work and breathing a sigh of relief, the news reporter came up, sat down, and asked, So where do you go to learn this kinda stuff? Recalling the hundreds of times I had heard this very question and knowing that its answer would lie at the end of a very long but satisfying conversation, I looked up and asked a question of my own: Where would you like to eat lunch?

Sean E. Richards is binder at Byzantium Studios

This article was republished with permission of the author.