The study of Shakespeare has, historically, thrived off of small inconsistencies in the great playwright’s printed editions. When you pick up a Folger edition of the Bard’s work and find that your favorite soliloquy out of the Pelican Shakespeare is ever so slightly altered, you experience the fruits of a literary labor that is as much a science as it is an art. The foundation of this science is called collation.

Collation, as Wikipedia rather unhelpfully informs us, is “the assembly of written information in a standard order.” To put it a bit more plainly, collation describes the physical attributes of a book, from the number of leaves and gatherings, to the way the leaves are folded, to any variations in the text across versions. In the case of Shakespeare, for instance, these descriptions allow us to distinguish between quartos and folios, designate how many pages are assembled and in what order, and track the sorts of changes that were common in an era where printers often made changes to their texts on the fly.

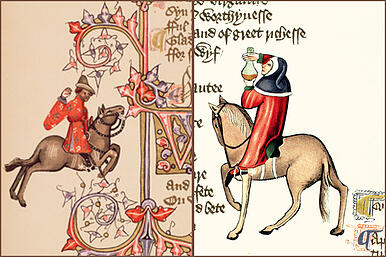

While the act of recording a text’s collation may seem like a labor of love, evoking images of bleary-eyed scholars hunched over stacks of candlelit manuscripts, it is actually a process that is aided by an ingenious piece of technology. By flipping rapidly between corresponding pages from different manuscripts (in the style of, say, a flip book), the Hinman Collator, named for a famed Shakespeare scholar, seems to make textual inconsistencies jump right off the page. This method not only enables us to uncover a text’s collation more quickly, but it ensures greater accuracy than one could reasonably expect from a scholar doing the task by hand. In this way, scholars not just of Shakespeare but of Chaucer and many other pre-19th century authors can establish a text and its variants in order to create scholarly editions.

Once the collation is established, that information is rendered in a formula that describes the way the book is assembled. In the case of the first folio, for instance, that formula is written out as follows:

2°: πA⁶(πA1+1, πA5+1.2), A-2B6, 2C2, a-g6, χ2g8, h-v6, x4, “gg3.4″(±”gg3″), ¶-2¶6, 3¶1, 2a-2f6, 2g2, “Gg6“, 2h6, 2k-3b6.

While the full explication of this information would require considerable space and technical expertise, it can at least be mentioned that the opening letter-sign combination (2°) is what distinguishes the text as a folio (with pages folded only once, as opposed to twice or thrice in a quarto or octavo, respectively) and that the remainder lets us know the number of gatherings, the number of sheets in each gathering, the order of the gatherings, any additional materials (such as a frontispiece or dedication page), and other information describing the characteristics of the physical document.

While collation may seem somewhat academic in this description, it actually has its roots in cold, hard practicality. In previous centuries, when books were printed and bound by different people, the collation (also known as the signature statement) was what enabled bookbinders to correctly assemble the various printed pages they had received into a finished book. The 2°, 4°, or 8° notation would tell the binders how many times each sheet was to be folded, and the rest of the collation would indicate the correct organization of those sheets into gatherings, and the correct order of the dedication page, frontispiece, etc. Crucially, the printer’s signature statement would also indicate how many sheets and gatherings the book should have, so that bookbinders could be certain that they had received all of the materials they needed to bind a complete copy of the book.

Although a lot has changed in the ensuing centuries, this type of collation can still be extremely useful for cataloguers and bibliographers. Especially with older volumes, the information found in a collation can indicate whether a volume is missing leaves or gatherings and let librarians know how it might differ from other versions of the same text. In this way, it’s possible to gain an understanding of what the physical book is like before even setting eyes on it. More than that, librarians can be sure that they’re looking at the correct volume in the correct condition (i.e. without additional missing pages). Though library catalogues vary on how rigorously to document each book’s physical properties, a thorough collation can be an invaluable resource.

Looking for more information? Read about signature statements, book cataloging, and collation here!