There’s an exciting new project at the University of Virginia that highlights the significance of the book as a physical object and the individual histories of library books. At a moment in which the physicality of university libraries (and others across the country) are under threat of depletion due to the looming presence of the electronic text, we couldn’t imagine a more compelling project than Book Traces. It’s a crowd-sourced web project sponsored by NINES at the University of Virginia, and it’s led by Andrew Stauffer, a professor of 19th-century literature at UVA. We had a chance to catch up with Professor Stauffer to ask some questions about the origins, current uses, and futures of Book Traces.

Books Tell You Why: Where did the idea for Book Traces start?

Books Tell You Why: Where did the idea for Book Traces start?

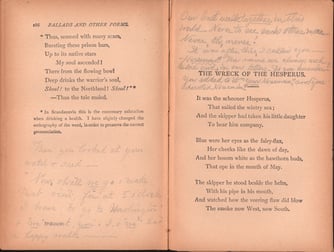

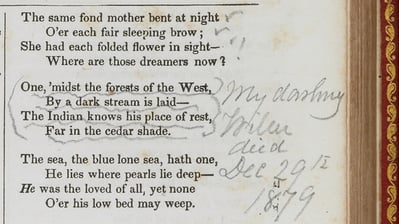

Andrew Stauffer: The project had its origins in an undergraduate class I was teaching on 19th-century poetry. I told the students to go into the stacks and bring back as many 19th-century copies of the works of Felicia Hemans as they could find, just so we could see the formats in which she circulated during the era of her great popularity. Many of them had inscriptions, underlining, and notes, and in the back of one of these books, we found that a mother had written a little elegy for her daughter, imitating Hemans’s style. And it made me think first, that this is important evidence for understanding how poetry was read and books were used in this era, and second, that a lot more of this evidence surely exists in the circulating collections of libraries across the country. So Book Traces began as an attempt to make more discoveries of this kind, and to make the case for the retention of multiple copies of non-rare books, because they can contain this kind of personal, artifactual evidence.

Books Tell You Why: What is the value of recording marginalia, writings, and other markings inside nineteenth and early twentieth-century books?

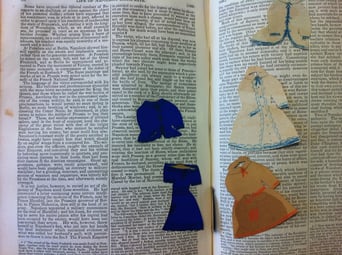

Andrew Stauffer: I believe that these marks and modifications by original owners constitute the great distributed archive of the history of middle-class reading and book use in an era when print was king. We can tell a lot about the history of different disciplines, subjects, and institutions by looking at large patterns in the data (types of marks per decade per subject, for example), as well as finding fascinating pieces of the past: we’ve discovered original anecdotes about Edgar Allan Poe, hand-drawn maps of civil war battles, personal letters from prominent local families, as well as touching personal items like locks of hair, photographs, and flowers, in addition to memorials, love notes, and records of everyday lives. People have always paid attention to the marginalia of famous people, or that written in books in much earlier eras (i.e., in medieval and early modern books). But we haven’t had a way to see nineteenth and early twentieth century marginalia of the common reader, because it is mostly uncatalgoued. Book Traces is trying to change that.

Books Tell You Why: Who is the project aimed at? Literature scholars? Librarians? Students? Book collectors?

Andrew Stauffer: Much of the work of discovery, cataloguing and research has in fact been done by students: they have been the ones combing the stacks, both at Virginia and a number of other universities where we have led Book Traces events, and finding examples, gathering evidence. So it’s been a terrific way to involve students at the undergraduate and graduate levels in original research in the print collections. At Virginia, librarians, scholars, and students are working together to develop a workflow and data model for the systematic recording of marks and modifications in the circulating collection. And the project also is meant to involve the larger library community, as an attempt to raise enthusiasm for a sustained national effort to discover and catalog these unique copies. Ultimately, we hope to provide a resource that will allow scholars to ask new questions about the history of reading and book use.

Books Tell You Why: If there's increasing interest in marginalia and other book markings, could such a shift change the way we think of rare book valuation? In other words, could seemingly banal marginalia actually become valuable as we move into the digital age?

Books Tell You Why: If there's increasing interest in marginalia and other book markings, could such a shift change the way we think of rare book valuation? In other words, could seemingly banal marginalia actually become valuable as we move into the digital age?

Andrew Stauffer: Booksellers and collectors have varying attitudes towards marks in books, variously characterizing them as damage or enhancements, usually depending on whether the person who made the mark is well-known or associated with the author. Again, the annotations in 15th or 16th century books, for example, are typically seen as valuable evidence, because of the rarity of all traces from those eras. The nineteenth century saw this explosion in print and readership that has left us with a massive archive of everyday reading. My hope is that Book Traces will allow us to see patterns within this material, and to view examples as part of an important picture of what books were. There are lessons to be learned as books go digital, and I think people are fascinated by marginalia now. I’ve said we seem to be living in a ‘marginalia moment’: the interest is widespread.

Books Tell You Why: Does the project currently include books in Special Collections departments, or does it focus solely on books found in the stacks?

Andrew Stauffer: Right now, we are focused on books in the circulating stacks primarily out of a sense of urgency: these collections are on the move, as libraries everywhere are consolidating and downsizing, or shifting lesser-used items into offsite storage, where browsing for marginalia is prohibitively resource-intensive. Our sense is that the books in Special Collections aren’t going anywhere, and that we can integrate them into the data down the line. But Book Traces is very interested in blurring the distinction between “special” and “general” collections, reminding everyone that plenty of unique artifacts are in the stacks.

Books Tell You Why: If a college student discovers an interesting marking in a 19th century library book, how can she get that information to Book Traces?

Books Tell You Why: If a college student discovers an interesting marking in a 19th century library book, how can she get that information to Book Traces?

Andrew Stauffer: She should go to http://booktraces.org and hit the “Submit a Book” button. She can upload a picture or two, fill out a few fields of metadata, and transcribe or describe if she likes, and then post it to the site. We have over 500 books that have been added that way, and are always looking for more. She could also contact her librarian and suggest a Book Traces event at her institution, where we could involve more people and make more discoveries in the collection.

Books Tell You Why: Can students at colleges and universities outside UVA get involved? How about individual library patrons who are members of their communities and discover interesting marginalia in books?

Andrew Stauffer: Same answer as above. At Booktraces.org, we are interested in examples from circulating collections all over North America, and beyond. Public libraries are certainly eligible. We are also trying to determine which libraries are particularly rich in this kind of material, so patrons should not only upload individual examples, but let us know if they think their library would be a good candidate for a more extensive survey.

Books Tell You Why: Do you imagine the project expanding beyond college and university libraries? What are the downsides of incorporating texts with marginalia from outside university library systems (i.e., from public libraries)?

Books Tell You Why: Do you imagine the project expanding beyond college and university libraries? What are the downsides of incorporating texts with marginalia from outside university library systems (i.e., from public libraries)?

Andrew Stauffer: Public libraries tend to have more rapid turnover of collections, so the long-term persistence of discovered copies is something we want to help insure. That said, some larger public libraries – NYPL, for example – would be ideal candidates for the project, and we are pursuing those collaborations. Ultimately, I can imagine moving into special collections, independent libraries, and even personal collections in pursuit of very specific clusters (for example, every marked copy of Hemans we can find). But the overall project at this point remains focused on circulating collections, which is where the vast majority of publicly-accessible nineteenth and early twentieth century books live.

Books Tell You Why: Do you think the Book Traces project could expand to include images from individual collectors with interesting marginalia? Why or why not? How about library books from very different periods?

Andrew Stauffer: As I said, I think scholars will want to use Book Traces data to pursue specific research questions that would need to involve books from all over. If, for example, Book Traces reveals that a particular kind of book tends overwhelmingly to be annotated in interesting ways, a scholar might want to follow up on that by calling for all copies of that book, reaching out to collectors, rare book librarians, and book dealers to build on that record of evidence.

Right now, because we are broad based project, we are focused on books that are publicly accessible. And we have emphasized the period 1800-1923, because books before that era tend to be in special collections and after that era (in the U.S.) are still in copyright. In fact, we are considering expanding to include books printed through the 1940s, when libraries began to buy books directly. Before WWII, most academic libraries acquired their books via donations from alums, local families, and other donors, and so they came bearing all of this interesting archival material. We aren’t interested in marks made in the books after they came into the libraries (i.e., patrons' marks) – only marks and modifications made by the books’ original owners. So the way libraries built their collections is crucial to the picture. We are the end of the cycle that created these legacy print collections and brought them into our libraries: we need to find ways to illuminate them and make them available to scholars, researchers, and collectors before we lose access to their unique evidentiary content.

Many thanks to Andy for taking the time to chat with us about Book Traces at the University of Virginia. We were thrilled to do this interview, and we encourage you to look into the project and the various ways you might participate.