Many elements combine to make for a deeply affecting children’s book. As in most any writing, story and characters are major factors in the success or failure of a children’s book. Likewise, an aesthetic is essential, one that is both captivating to children and palatable to the adults who often purchase and read the books aloud. While there’s no denying the importance of these elements, it seems likely that for many the most crucial element of a good children’s book is its artwork. Artwork, after all, is what imbues the plot, the characters, and the aesthetics with a sense of life, enriching them simultaneously with equal parts reality and imagination. This, in a nutshell, is how we can account for the success of Peter Spier.

Peter Spier, whose 1977 work, Noah's Ark, would ultimately win him the Caldecott Medal, seemed primed since childhood to become a beloved illustrator. He was born in Amsterdam, North Holland to Jo Spier, who was himself a well regarded artist and illustrator, and Tineke Van Raalte. He has remarked that, while growing up in the “small romantic village” of Broek, “[he] cannot remember a time when [he] did not dabble with clay, draw, or see someone draw… [he] grew up with it all.” Though this quote may make his childhood sound idyllic, during World War II, it was anything but.

Peter Spier, whose 1977 work, Noah's Ark, would ultimately win him the Caldecott Medal, seemed primed since childhood to become a beloved illustrator. He was born in Amsterdam, North Holland to Jo Spier, who was himself a well regarded artist and illustrator, and Tineke Van Raalte. He has remarked that, while growing up in the “small romantic village” of Broek, “[he] cannot remember a time when [he] did not dabble with clay, draw, or see someone draw… [he] grew up with it all.” Though this quote may make his childhood sound idyllic, during World War II, it was anything but.

Spier and his father, both Jewish, became two of the nine prisoners held in Villa Bouchina, an abandoned church, before being sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Luckily, both Spier and his father survived until 1945, when most of the Dutch prisoners were sent to Switzerland in exchange for a hefty ransom. Following the war, Spier studied art at Rijksakademie (an artist’s residence fashioned out of a disused army barracks). He also served a four year stint in the Royal Netherlands Navy. Shortly thereafter, the entire Spier family left the Netherlands for America.

Though Spier, on arriving in the United States, first took work as a commercial artist, success as a children’s illustrator was not terribly long in coming. By 1957, he had illustrated his first book, Phyllis Krasilovsky’s The Cow Who Fell in The Canal. By 1961, he was producing books for which he was both writer and illustrator, beginning with Island City: Adventures in Old New York.

Though Spier, on arriving in the United States, first took work as a commercial artist, success as a children’s illustrator was not terribly long in coming. By 1957, he had illustrated his first book, Phyllis Krasilovsky’s The Cow Who Fell in The Canal. By 1961, he was producing books for which he was both writer and illustrator, beginning with Island City: Adventures in Old New York.

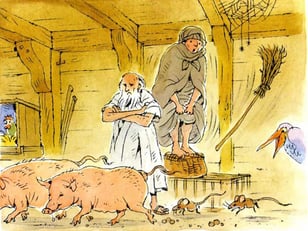

In addition to winning the 1977 Caldecott Medal for Noah’s Ark, Spier won a Christopher Award in 1980 for People, which also earned him a spot on the shortlist for the National Book Award for Children’s Nonfiction. After even a brief look at some of his work, it’s not hard to see why. His pages are exciting and full of detail. They come alive with an authenticity that comes from Spier’s refusal to work from photographs. Far from superficial, however, his detailed drawings contain a wealth of information. His artwork informs the corresponding text with historical information, character building, and often-subtle visual humor. Truly, Peter Spier remains a treasure in the world of children's book illustrations.