As book collectors, we know the importance of the book as a physical object. From marginalia to dust jackets, numerous factors come in to play when determining what to collect and how much any given collectible is worth. Indeed, the condition of the physical book goes a long way in determining its value to collectors, and in many case the look of a book—from its illustrations to its binding and everything in between—charts the course for collectors.

Many ‘groupings’ of collectible books exist, and they often direct the collecting ways of interested bibliophiles. For example, some collectors focus on collecting the leather-bound Franklin Library editions. Others have a special place in their hearts for the Penguin Classics, either the Deluxe Editions or the familiar black-spine series. Still others look to fine-press operations for their aesthetic outputs. One of the most important and valuable ‘groupings’ of collectible books is the Limited Editions Club and its publications.

What is the Limited Editions Club?

The Limited Editions Club, much as its title suggests, was a subscription-based book club intent on circulating limited edition copies of classic titles to its members. Founded in 1929 in New York City by George Macy, the Club consisted of a select group of book enthusiasts limited in number to 2,000. The only criterion for membership was a willingness to subscribe to receive the limited edition books put out by the Club. Therefore, club membership could not exceed the number of copies printed, making it an exclusive group; the print run for each title was limited to 1,500 at first and later 2,000 before dropping down to a few hundred copies for each publication. The first book published by Macy was The Travels of Lemuel Gulliver with illustrations by Alexander King.

|

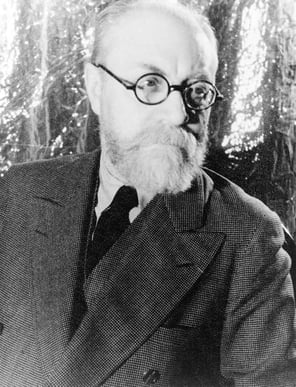

| Henri Matisse, illustrator of Ulysses, one of the LECs most famous works |

The books that club members purchased were truly works of art. Macy went about obtaining the services of some of the most creative minds of his time to illustrate the classic texts. So, not only did club members receive finely printed copies of the texts, the pages of these books were also given new life thanks to illustrations by such legendary artists as Arthur Rackham, Pablo Picasso, Norman Rockwell, and Henri Matisse, among others. The artists were also asked to sign their work.

What titles did the Club publish?

The Limited Editions Club published a total of 548 titles, between 1929-1985. From the mid-1980s-2000s, fewer and fewer titles were published—as opposed to 10-12 each year, as the Club published in its prime, only about 3-4 titles were put out, and even this number dwindled with time.

The books are beautiful, and the titles are what some may consider fan-favorites, or at least they are quite recognizable. Titles of note include Ulysses by James Joyce, illustrated by Henri Matisse, which many argue is one of the most valuable Limited Editions Club publications. It was published in 1935, and 250 copies out of the original 1,500 were signed by James Joyce. Also of import, the illustrations Matisse produced relate to Ulysses only through a stretch of the imagination. Indeed, they are more suited for Homer’s Odyssey than Joyce’s Ulysses.

Either way, getting your hands on a signed copy, then, is extremely difficult and supremely valuable. Abebooks notes that they sold such a signed copy for over $6,000. Others who’ve had their work immortalized in the form of Limited Edition Club publications include Tennessee Williams, Robert Frost, Jane Austen, Ray Bradbury, Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, George Eliot, Victor Hugo, Dante, and so many more.

Some Limited Editions Club books are also signed by other important relevant figures. For example, the Limited Editions Club’s publication of Robert Frost’s The Complete Poems of Robert Frost is signed not only by illustrator Thomas Nason, but also by designer Bruce Rodgers, and Frost himself—a triple threat. The opportunity to have an author signature on Limited Edition Club publications came about as the Club evolved and published some contemporary classics. Likewise, Lewis Carol’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass were also each signed by Alice Hargreaves, who, as a young girl, inspired Carol’s work.

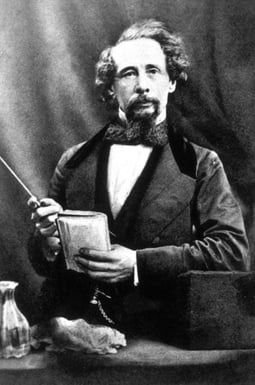

An interesting find—beyond illustrations—in a particular Limited Editions Club book must be noted in the 1937 LEC publication of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Great Expectations has several, variant endings penned by Dickens in an effort to appease writer and friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who, after reading the original ending, implored Dickens to re-write. Dickens did, and the re-written ending was published. The original ending was first seen in John Forster’s biography of Dickens in 1870. In 1937, George Bernard Shaw included the original ending in his preface to the Limited Editions Club publication of the novel. Collectors of Dickens, then, may seek the LEC publication of Great Expectations along with the first edition in order to acquire the entire body of his work, at least for this particular novel.

An interesting find—beyond illustrations—in a particular Limited Editions Club book must be noted in the 1937 LEC publication of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Great Expectations has several, variant endings penned by Dickens in an effort to appease writer and friend Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who, after reading the original ending, implored Dickens to re-write. Dickens did, and the re-written ending was published. The original ending was first seen in John Forster’s biography of Dickens in 1870. In 1937, George Bernard Shaw included the original ending in his preface to the Limited Editions Club publication of the novel. Collectors of Dickens, then, may seek the LEC publication of Great Expectations along with the first edition in order to acquire the entire body of his work, at least for this particular novel.

It was Macy’s intent to give readers unique and worthwhile materials with his LEC publications, and there are numerous examples of him doing just that. In the 1939 Limited Editions Club publication of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, never before seen material was included. Likewise, after tracking down the original illustrator of Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, E. W. Kemble, Macy commissioned him to create a title page for his 1933 edition of the book which then also included Kemble’s earlier sketches.

Collecting Tips and Insights

Collecting Limited Editions Club books is a noble pursuit. It’s also a challenge! Because of the rarity of each title (see Ulysses above), copies that come into the marketplace are often expensive. We’d recommend—as with any and all book collecting efforts—that you educate yourself about the titles you wish to acquire; background research will be essential in order to ensure that you’re spending the proper amount of money to obtain the book you’re seeking. (Editors note: See the comment section below for additional collecting points.)

Keep an eye on library and used book sales. You never know when a great book may be lying right out in the open, just waiting for an astute collector to find it and give it a home.

Some of our favorite Limited Editions Club publications include Music, Deep Rivers in My Soul by Maya Angelou. Angelou wrote this original work for the LEC, and she implored illustrator Dean Mitchell to aid in the project. He contributed six color etchings to the book. Likewise, Angelou’s work inspired an original jazz composition by Wynton Marsalis. A collaboration between Marsalis and Angelou—him playing while she reads—should be included with copies of this book, first published in 2003.

We also love the LEC version of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, published in 1982 and illustrated by Joseph Mugnaini. This publication is bound in anti-flammable aluminum with black, red, and white lettering. The aluminum foil binding tends to scuff and dent, so if you’re in the market for this collectible, be sure to check on condition as it pertains to price.

Other items that are significant when combined with Limited Edition Club publications are the Club’s monthly newsletter, referencing the book in question. Often times, book sellers will include these pieces of ephemera with the books, and they add value to the collectible.

Finally, we also treasure the LEC publication of Mark Twain’s Slovenly Peter (1935). It is the first edition of Twain’s translation of the classic German children's book Der Struwwelpeter. In the foreword to the Limited Editions Club publication, Twain’s daughter Clara provides insight into why Twain chose to translate the work, stating that he felt there are aspects of childhood that are universal and know no one, particular language.

A total of 1,500 copies of the LEC’s Slovenly Peter were published and include water color illustrations by Fritz Kredel who used the same style of the original German author and illustrator, Dr. Heinrich Hoffman.

Sources: Majure, The New Yorker, Biblio