Since Saul Bellow won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1976, only a few other American writers (the inimitable Toni Morrison, who earned the sought-after medal in 1993 and most recently, Bob Dylan, come to mind) have accomplished the same feat. This fact speaks to a number of phenomena, but it chiefly indicates the way that Bellow’s fiction represented a sort of capstone in American fiction. Born in Quebec to Lithuanian-Jewish immigrants, Bellow soon moved to Chicago, a city he would come to immortalize in his works. Perhaps more than any other writer, Bellow brought the modernist and intellectual traditions in 20th century fiction into conversation, crafting unforgettable characters in the process.

Though the Nobel Committee gave Bellow his award more or less on the heels of the success of his Pulitzer Prize for Humboldt’s Gift, that particular work has not retained the same prestige or sought-after status as some of Bellow’s earlier work. For collectors, one likely wants to start by looking earlier in Bellow’s career.

Though the Nobel Committee gave Bellow his award more or less on the heels of the success of his Pulitzer Prize for Humboldt’s Gift, that particular work has not retained the same prestige or sought-after status as some of Bellow’s earlier work. For collectors, one likely wants to start by looking earlier in Bellow’s career.

The Adventures of Augie March (1953) remains one of the most highly regarded pieces not just in Bellow’s oeuvre but in American literature at large. It follows its title character’s childhood and early-adulthood in depression-era Chicago, pairing the picaresque narrative structure for which Bellow would become known with the type of soaring prose that lends so many of his works part of their appeal. Though less well-preserved copies might be had fairly cheaply, a first edition in reasonably good shape could go for several thousand dollars.

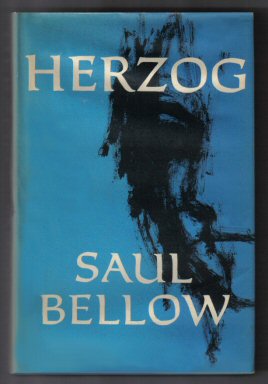

Released only a few years later, Herzog (1964) is another must-have for those seeking to collect Bellow’s works. The novel earned him his second of three National Book Awards and is a staple of "best of" lists for 20th century novels. The book is centered on Moses E. Herzog (whose name is an allusion to a bit-character in notable Nobel-snub James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922)) as he goes about dealing with the emotional fallout from his divorce. It brings the intellectual air of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood (the home of the University of Chicago, where Bellow and Herzog were professors) alive by way of Herzog’s stream of consciousness, rendered in the form of mentally-composed letters to scholars, philosophers, and real-life acquaintances. Along with Augie March, it is perhaps the most eloquent argument for Bellow’s enduring greatness, making it an ideal cornerstone for a collection.

Released only a few years later, Herzog (1964) is another must-have for those seeking to collect Bellow’s works. The novel earned him his second of three National Book Awards and is a staple of "best of" lists for 20th century novels. The book is centered on Moses E. Herzog (whose name is an allusion to a bit-character in notable Nobel-snub James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922)) as he goes about dealing with the emotional fallout from his divorce. It brings the intellectual air of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood (the home of the University of Chicago, where Bellow and Herzog were professors) alive by way of Herzog’s stream of consciousness, rendered in the form of mentally-composed letters to scholars, philosophers, and real-life acquaintances. Along with Augie March, it is perhaps the most eloquent argument for Bellow’s enduring greatness, making it an ideal cornerstone for a collection.

Because Herzog finally brought its author a modicum of commercial success, it’s the works that predate it that can be most likely to have a cache of rarity compared to his later works. And, undoubtedly, Henderson the Rain King (1959) and Seize the Day (1956) are classics that predate Bellow’s explosion. At the same time, later works like Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970), which is separated from Herzog only by Mosby’s Memoirs and Other Stories (1968), and Ravelstein (2000), a thinly veiled romans a clef about Bellow’s colleague Alan Bloom, are also justifiably beloved. These books may have a stronger claim to necessary inclusion in a collection of his works than, say, his first two novels, Dangling Man (1944) and The Victim (1947). These later works often give some of Bellow’s most biting insight into "the big-scale insanities of the 20th century.”