Despite being a country of fewer than 5 million people, Ireland boasts four Nobel Prize in Literature winners: W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Becket, and Seamus Heaney. For those of you keeping score at home, that’s the highest Literature Nobel Laureates per capita outside of St. Lucia, which counted the late poet Derek Walcott among its 150,000 or so residents, even without James Joyce (who was famously snubbed) to round out the list. (Sweden appears to be a close third, with 8 prizes and a population just under 10 million). In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we’ll be turning the attention to two of the Emerald Isle’s most gifted writers: George Bernard Shaw and Seamus Heaney.

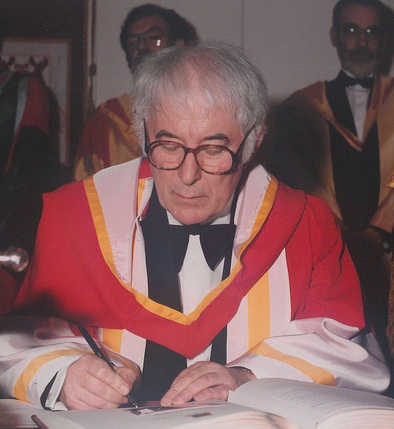

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney was awarded literature’s most coveted prize in 1995, "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past," and a quick glance at nearly any of his poems makes it obvious that the Nobel Committee was not, in that instance, prone to overstatement. For many, Heaney (who was born in Northern Ireland in 1939) is the poet laureate of Ireland’s Troubles, a consistent voice for peace and understanding in a often violent and frightening world.

Heaney’s resume includes not just poetry by a number of prose works, plays, and translations (he could translate from a number of languages, including Latin, and famously translated Beowulf (c. 1010) from the Old English, a task that was also undertaken in his day by J.R.R. Tolkien), but it tends to be his verse that is most coveted by collectors. As such, any of Heaney’s poetry makes a strong basis for starting your collection, though critical opinion often gives special attention to his first and last works, Death of a Naturalist (1966) and Human Chain (2011), respectively.

Though Heaney’s work was largely written in the second half of the twentieth century, poetry has never quite reached the heights of big business. As a result, many of Heaney’s works were subject to fairly small initial print runs. Despite the popularity he would attain during his lifetime, first printings can be fairly hard to come by, and signed first printings can run in the thousands or tens of thousands of dollars. Though, in some ways it seems almost fitting that a palpable aura would continue to hang around books of such mystery and eloquence, from a rare 20th century artist who took to heart Shelley’s dictum that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

George Bernard Shaw

In 1925, the Nobel Committee awarded the Literature prize to Shaw "for his work which is marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty." Though Shaw, who had been producing dramatic works since the 1890s, was inarguably a giant of world letters, it’s hard to imagine that the Nobel Committee’s decision was uncontroversial. After all, Shaw had fashioned himself over the course of dozens of pamphlets and polemical works into a world-class iconoclast, championing a host of unpopular opinions. History has been kinder to some of these opinions than others (he was an early opponent of vaccinations and a noted eugenicist; he was also a vegetarian and a frequent critic of imperialism in various forms), but many of his works have stood the test of time.

Some of Shaw’s most well-known plays include Major Barbara (1905), Man and Superman (1902), and Pygmalion (1912) (which became the basis for My Fair Lady (1956)), but the prolific scope of his oeuvre makes it difficult to get a handle on Shaw as a writer. Of plays alone he wrote more than 50, including his last dramatic work, Shakes versus Shav (1949), which features puppets of Shaw and Shakespeare arguing with one another.

Beyond plays, he wrote scores of other works, from novels and works of criticism to a rhyming picture book about an English village (Bernard Shaw’s Rhyming Picture Guide to Ayot Saint Lawrence, published just before his death in 1950), the result is a landscape that put would-be collectors in an odd position. A complete set of Shaw’s writings is a lofty goal even before we think about the provenance of the various volumes, and defining exactly which of his works count as major is far from a clear-cut task.

Beyond plays, he wrote scores of other works, from novels and works of criticism to a rhyming picture book about an English village (Bernard Shaw’s Rhyming Picture Guide to Ayot Saint Lawrence, published just before his death in 1950), the result is a landscape that put would-be collectors in an odd position. A complete set of Shaw’s writings is a lofty goal even before we think about the provenance of the various volumes, and defining exactly which of his works count as major is far from a clear-cut task.

As a result, the most highly prized items for Shaw’s collectors tend more toward curiosities than major works. Typed letters, speeches, and short-run pamphlets often run in the multiple thousands of dollars, but the diffuse nature of Shaw’s work means that one can establish a respectable collection without relentlessly pursuing expensive, big ticket items. Even some modern, fine press editions of the critic and playwright’s work have their own distinctive appeal, much like Shaw himself—a man who never shied away from trying to write his way out of the world’s myriad of problems.