A snapshot of 19th Century children’s literature and one of modern day children’s literature would make for a very interesting before-and-after photo. In the time before children’s lit giants like Dr. Seuss, Maurice Sendak, or Shel Silverstein, children’s literature often defaulted to mortality or cautionary tales designed to teach children the dangers of greed or gluttony—think of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, as their takes on Little Red Riding Hood and Beauty and the Beast are far afield from the Disney versions.

While these tales relied heavily on the use of irony, sardonic humor, grim imagery, and violence, forays into the sinister—particularly through the vehicle of deception—were commonplace as both thematic strains and devices to advance plot and character. Whether at the expense of the reader or the characters themselves, the use of sinister elements such as deception are most prominent in the following three classic examples of 19th Century children’s literature. Each removes the kid gloves when it comes to setting up expectations and then subverting those expectations for deeply-felt, visceral results.

The Little Match Girl

Perhaps one of the better known tales of Hans Christian Anderson, The Little Match Girl has been deceiving young adult audiences with its deceptive end-of-story twist since its initial publication in 1845. The story centers on a poor, homeless girl selling matches on a street corner on New Year’s Eve. In what can be assumed to be the early stages of hypothermia, the girl strikes several matches to keep warm before dosing off to dream of a better life—and reminisce about her dead grandmother—while lying in the gutter. The girl’s fantastical visions come to a crashing halt as the reader discovers she’s actually died from exposure, and in the final scene of the story is transported to Heaven to be reunited with grandmother.

It’s a plot movement Hans Christen Anderson gave little warning of, and while he often defended the ending as a happy one, readers have long been in agreement Anderson’s use of the sinister and deception is part of what gives the story such staying power.

Goldilocks and the Three Bears

No pun intended, but it bears noting there are several versions of this classic fairy tale, each of which have their own mildly-disturbing take on the use of the sinister and deception. The most well-known version comes in 1837 by author Robert Southey and is collected in a book of essays called Call the Doctor. Southey’s incarnation retains much of the plot readers are used to, with one notable exception: Goldilocks is envisioned as an old woman. While the change from little girl to old woman is not by itself terribly sinister, several other versions of Southey’s tale delve into the grim with little apology. An 1831 oral version of the story has Goldilocks escaping from the three bears only to be impaled on the steeple of St. Paul’s Cathedral as retribution for her trespassing. Other iterations published throughout the 1800s end with the three bears devouring both the young girl and old woman version of Goldilocks.

Once again, it's the reader who is duped into believing both the little girl and the old woman will manage to flee the three bears, only to be proven otherwise in particularly grizzly fashion.

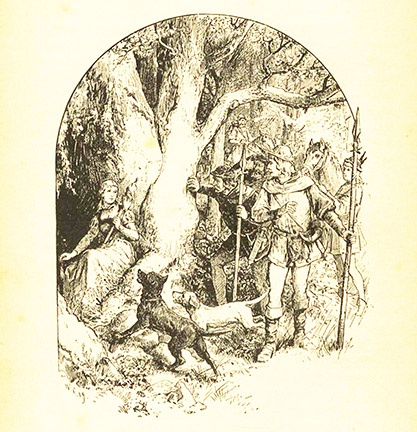

Molly Whuppie

Besides being a whole lot of fun to say, the old Scottish folktale Molly Whuppie is one of the more contemporary pieces of children’s literature employing elements of the sinister. Collected in the 1890 book English Fairy Tales by Joseph Jacobs, the story centers on Molly and her two siblings who are abandoned in the woods by their parents. Left to their own devices, the children seek shelter on a farm and enter into a series of perilous events with a giant, ogre-like man, his wife, and threats of being consumed whole if they don’t obey the rules of the house. The story has a number of twists and turns, many of which involved exploitation of Molly for food and drink, safe passage, and eventual marriage to a king after she and her siblings escape the clutches of the giant. The story also eludes to several deaths, including that of the giant’s wife, and it can be inferred Molly throws her siblings under the bus toward the end of the tale to secure her own safety.

In the case of Molly Whuppie, it’s the characters who experience deception at the introduction of sinister elements: the giant’s wife, who is promised no harm will come to her, and the inferred bad fortune Molly heaps upon her siblings in order to save her own skin.