Before he wrote the bulk of the books that would make him a giant of children’s literature, Theodor Seuss Geisel took a stand. Fascism had spread across Europe, and the Third Reich was bringing war and slaughter to its neighbors and citizens. Congress and the press debated what role America should play in the growing conflict, but Geisel was sure of what had to be done. Nazism, he knew, had to be fought.

Theodor Geisel was born to German immigrant parents, and German was spoken in his home growing up. Geisel respected both America and his ancestral homeland, and in his vision, this meant opposing the unacceptable and unconscionable rise of Hitler and the Nazis.

Theodor Geisel was born to German immigrant parents, and German was spoken in his home growing up. Geisel respected both America and his ancestral homeland, and in his vision, this meant opposing the unacceptable and unconscionable rise of Hitler and the Nazis.Geisel’s entrance to the public forum came in 1940, after he submitted a cartoon and was thereafter signed on as senior editorial cartoonist for the left-leaning PM magazine. He had published his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, just three years before. He had already adopted the “Dr. Seuss” name, and had displayed the distinguishing characteristics of his illustrations. Indeed, Geisel’s more whimsical and childlike leanings sometimes intersected with the practical seriousness of his cartoons. One work of war-bond propaganda commissioned by the Treasury Department, for instance, depicts stylized deer—ten “bucks,” out of which one it recommended dedicating to war bonds.

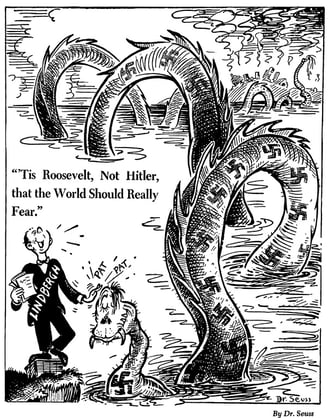

But even before the United States entered the war, Geisel’s cartoons skewered the likes of Charles Lindbergh, the German-American Bund, and the America First isolationists, whom Geisel regarded as tacit allies to Nazi progress. In a cartoon that has lately gone somewhat viral online, a mother reads to her children from a storybook called “Adolf the Wolf,” saying, “And the Wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones … But they were Foreign Children and it didn’t really matter.” The stakes, Geisel felt, were too high to allow passivity.

Geisel produced a vast wealth of cartoons, some 400 in just two years, or one every few days, and he would later confess many were “hurriedly and embarrassingly drawn” and “full of snap judgments.” When Geisel heard Pearl Harbor was bombed in December 1941, he put down his copy of the newspaper and began drawing a cartoon of an ostrich named “Isolationism” blown away by an explosion labeled “War.” It was what he predicted the global conflagration would come to all along.

Geisel’s cartoons lampooned the likes of armchair generals, who knew the best way to conduct a battle in hindsight. He made a parody of gas-guzzlers and those indulgent enough to complain about or thwart rationing and recycling initiatives. He typically condemned Republicans bent on taking any other stand than non-involvement, and generally supported the president. Among his clear dislikes were anti-Semitic and anti-black prejudices, which he saw as stifling to progress and the country’s war effort. One of Geisel’s own favorites was a cartoon in which a man at an organ is advised that the way to proper harmony is to play all the keys together—black and white alike.

Tis Roosevelt, Not Hitler, that the world should really fear, June 2, 1941, Dr. Seuss Political Cartoons. Special Collection & Archives, UC San Diego Library

But the story of Theodor Geisel’s political cartooning is not a simple, right-side-of-history narrative. His offensive depictions of Japanese people are notorious. When representing Japan alongside Hitler, Geisel often opted not to draw General Tojo or Emperor Hirohito, but instead a general caricature of a Japanese person. In other cartoons, he cast Japanese-Americans as traitors to the country, conspiring as sleeper cells to undermine the war effort.

In 1943, Geisel left his post as a cartoonist to work in more direct assistance to the government, and joined the Air Force to begin making films. Lighter fare, like the Private Snafu series, consisted of cartoons that exemplified proper behavior and protocol by following a protagonist who did almost everything wrong. The Private Snafu character is tempted by seductive spies and gets overconfident because he is equipped with state-of-the-art weapons. They were voiced by Mel Blanc, the same actor behind Bugs Bunny. For all their silliness, these cartoons were an official military secret and closely guarded as such.

Other films include postwar propaganda films such as Your Job in Germany, which outlined the American service member’s role in reconstructing Europe. Among its assertions was a non-fraternizing rule, warning viewers that the German people were deceitful, and interaction could lead Americans and the national interest astray. Perhaps not enjoying its heavy-handed prescriptions, in a screening with top military officials including Dwight Eisenhower, General Patton screamed a curse and left the room. Another film, Our Job in Japan, concerned the remnants of the other theater of war. It was later turned into Design for Death, a study of Japanese culture that won the Oscar for Best Documentary, and what some consider something of an atonement for Geisel’s offensive depictions of the Japanese during the war, an effort of reconciliation he extended with the slight political message of his famous book, Horton Hears a Who (1954).

In the following decades, Dr. Seuss went on to write and illustrate some of the most beloved children’s books of the century. But some forget that before all that, he sent his art to war.