Today she’s known as the “doyenne” of Irish literature and a respected elder stateswoman of arts and letters throughout the English speaking world. Her awards are numerous and accolades esteemed, but when Edna O'Brien broke onto the international literary stage in 1960 with the publication of her novel The Country Girls, she was a struggling devotee of James Joyce working as a reader for a London-based publishing house.

Afterwards, however, despite robust sales and universal critical acclaim, O’Brien found herself in the eye of a storm of backlash stemming from The Country Girls and the publication of its two sequels—The Lonely Girl (1962) and Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964)—for the characters which she wrote about and how their actions and inner-most feelings flouted the conventions of Irish society in the early years following World War II.

Afterwards, however, despite robust sales and universal critical acclaim, O’Brien found herself in the eye of a storm of backlash stemming from The Country Girls and the publication of its two sequels—The Lonely Girl (1962) and Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964)—for the characters which she wrote about and how their actions and inner-most feelings flouted the conventions of Irish society in the early years following World War II.

O’Brien’s Girls trilogy was not only a source of outrage among many Irish readers of the day, the books were also banned by church leaders throughout the country for their frank confrontations of societal norms. Copies of O’Brien’s novels were often burned as part of religious gatherings, and though not necessarily exiled, it took O’Brien a number of years to return to her home country, and she still resides in England today.

So what was it exactly about O’Brien’s debut novel that pushed so many buttons? First, let’s examine the plot.

Completed in just three weeks, the novel centers on Caithleen “Kate” Brady and Bridget “Baba” Brennan, two childhood friends who decide in their late adolescence to shrug off the shackles of domestic responsibility and expectation and move from their small village to the big city in search of love, lust, and adventure. Kate and Baba encounter all kinds of misadventures during their travels, including explicit depictions of sex, alcohol use, and other debaucherous behavior.

While the plot of The Country Girl may seem tame by today’s standards, picture yourself in 1960 Ireland: the country was still rebuilding following the bombardment of World War II; the national economy was struggling to regain its footing; austerity measures, both in terms of physical and worldly pleasures still ruled the day; and the church was fostering a strict adherence to religious doctrines that expressed a woman’s place was in the home as a dutiful mother and wife.

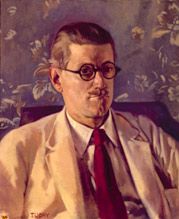

In this context, it’s easy to see why O’Brien’s novel was met with such vitriol and disdain, both for the subject matter but also for the way in which she delivered those subjects. Up until The Country Girls, much of Irish literature was primarily focused on language—the artfully crafted image, the deft turn of phrase, the beautifully rendered scene. O’Brien, however, took her cues from world-renowned author James Joyce and concentrated her efforts less on the poetics and more on the psychology of her characters and the motivations and desires that drove them.

In this context, it’s easy to see why O’Brien’s novel was met with such vitriol and disdain, both for the subject matter but also for the way in which she delivered those subjects. Up until The Country Girls, much of Irish literature was primarily focused on language—the artfully crafted image, the deft turn of phrase, the beautifully rendered scene. O’Brien, however, took her cues from world-renowned author James Joyce and concentrated her efforts less on the poetics and more on the psychology of her characters and the motivations and desires that drove them.

And thematically, O’Brien’s novel broke new ground in the kinds of topics writers—female writers in particular—were able to discuss in their writing. Kate and Baba’s rebellious, caution-to-the-wind attitudes were not only the outward manifestation of O’Brien’s inner self—she acknowledged just so in her 2002 bestselling memoir Country Girl—but were also something of wish fulfillment for a number of Irish woman as the Woman’s Liberation Movement began to bubble beneath the surface in places like England and the United States.

It was a seismic shift in narrative and tone—one that would dominate O’Brien’s work from then on—and one those closest to O’Brien had a difficult time stomaching. As she writes in her memoir, O’Brien’s parents were disgusted with The Country Girls and its sequels, and even her husband, writer Ernest Gebler, denounced the book and her efforts as a writer, which O’Brien has said led directly to their divorce not long after the Girls trilogy was completed.

In her memoir, O’Brien writes passionately about her own work and experiences, likening much of Kate and Baba’s character traits to an amalgamation of her own. Much like the girls in the novel—the friendship of the two becomes strained and contentious as they discover their true selves and what they want out of life—O’Brien paid something of a heavy personal price for following her heart.

But in doing so, she opened the door for a number of other Irish writers to confront their own interior landscapes, including the likes of Anne Enright, Nuala O’Foolin, and Colm Tobin. And O’Brien continued to make grand gestures on the international literary stage, especially with the publication of her 2011 collection of short stories, Saints and Sinners, which was awarded the prestigious Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award.

Yes, O’Brien’s girls may have been a source of struggle and strife, but without them it’s safe to say there would be a gaping hole in the history of Irish literature for both men and women.