In Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers (2008), the popular sociologist outlines the role that timing played in Bill Gates’ runaway success in the world of software. He suggests that because Gates was one of very few people of his generation who had access to computers as a teenager and came of age at the appropriate moment to eventually become a software developer, he (or someone fitting his description fairly) was destined to find such a level of success. And of course the same logic can be applied elsewhere. Thor Heyerdahl, for instance, was no doubt destined for a hugely important career as an experimental archaeologist, anthropologist, and explorer of the South Pacific from the moment he gained access to what was then the world's largest private collection of books on Polynesia.

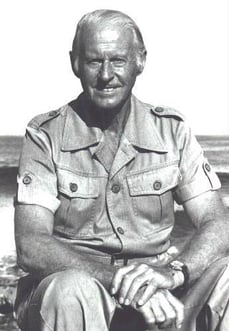

Indeed, Thor Heyerdahl had Bjarne Kropelien's collection of books and papers on Polynesia at his disposal. The collection was housed in Oslo, Norway, in close proximity to where Heyerdahl studied at the University of Oslo. Heyerdahl—who took on his life as an adventurer and ethnographer following his stint in the Free Norwegian Forces during World War II—is perhaps most famous for his Kon-Tiki expedition.

Indeed, Thor Heyerdahl had Bjarne Kropelien's collection of books and papers on Polynesia at his disposal. The collection was housed in Oslo, Norway, in close proximity to where Heyerdahl studied at the University of Oslo. Heyerdahl—who took on his life as an adventurer and ethnographer following his stint in the Free Norwegian Forces during World War II—is perhaps most famous for his Kon-Tiki expedition.

Hoping to cast doubt on the theory that Polynesia had been settled from West to East exclusively by those of South Asian descent, Heyerdahl and five others constructed a ship out of only materials that would have been available to indigenous South American civilizations and successfully sailed it across the Pacific to French Polynesia, firmly substantiating the idea that indigenous South American contact in the region could have preceded Europe’s “discovery” of the islands.

Heyerdahl's book on the subject, while scientific in its way, also had considerable popular appeal, drawing, perhaps, readers of adventure and travel literature.

In a similar vein, Heyerdahl would come to undertake expeditions from Morocco to Barbados and from Iraq to Pakistan. In both instances, he and his compatriots crafted vessels (built of papyrus and reeds) that might easily have been built by the ancient civilizations of their respective regions. By successfully landing these ships at their destinations, Heyerdahl again proved the feasibility of contact between cultures that had been believed to be isolated from one another before European contact. These experiments had, if nothing else, the potential to inform the future of linguistic and anthropological study in the regions.

While Heyerdahl’s voyages were often fruitful, the analyses he presented in his accounts of the journeys have seldom become accepted as scientific fact. The West-East model of Polynesian settlement still pervades in light of considerable genetic and linguistic evidence (though genetic evidence has lent some credence to the notion of pre-European contact between Peru and Polynesia), and Heyerdahl’s late-in-life quest to find a lost civilization in the USSR purported in mythology to have settled Norway was a point of derision for many.

While Heyerdahl’s voyages were often fruitful, the analyses he presented in his accounts of the journeys have seldom become accepted as scientific fact. The West-East model of Polynesian settlement still pervades in light of considerable genetic and linguistic evidence (though genetic evidence has lent some credence to the notion of pre-European contact between Peru and Polynesia), and Heyerdahl’s late-in-life quest to find a lost civilization in the USSR purported in mythology to have settled Norway was a point of derision for many.

These facts, however, seem to do little to tarnish Heyerdahl’s legacy. While the beloved adventurer may not have been an impeccable scientist, he did a great deal to further theories of cultural diffusion, espousing all the while a strong belief in the fundamental same-ness of human beings.

He was at times a literal crusader for the expansion of quotidian worldviews and one need only look at his 1978 boat-burning protest (in which his still-seaworthy reed vessel was set ablaze in Djibouti in order to make a statement about the Western world’s inadequate response to that year’s violence in Africa and the Middle East) to understand the high regard he still enjoys in the popular imagination more than a decade after his death.