Thinking about the contemporary politics of the Middle East, few of us immediately think of the rich history of Iranian literary production. However, modern Iran—from the time of the Shah through to the depths of Islamic fundamentalism and the suppression of human rights—has produced some of the most interesting texts by and about women. What does feminism look like in Iran? We might begin to answer such a question by reading the poetry of Forough Farrokhzad, ending with the graphic novel Persepolis, written by Marjane Satrapi, and exploring various genres in between.

Poetry of Feminism and Resistance

As a very brief introduction to the history of modern Iran, we thought you should have an idea of some key political moments that influenced the literature arising from the country. In 1935, the name Iran was officially adopted as the name of the country (known previously, as you might know, as Persia). Following a series of political struggles during World War II and the years immediately following, a 1953 coup d'état led to the reinstallation of the Shah. With a promise to modernize and Westernize the country, the Shah’s policies allowed literary production to flourish.

As a very brief introduction to the history of modern Iran, we thought you should have an idea of some key political moments that influenced the literature arising from the country. In 1935, the name Iran was officially adopted as the name of the country (known previously, as you might know, as Persia). Following a series of political struggles during World War II and the years immediately following, a 1953 coup d'état led to the reinstallation of the Shah. With a promise to modernize and Westernize the country, the Shah’s policies allowed literary production to flourish.

One of the most significant female poets of the twentieth century, Forough Farrokhzad published works of poetry from Tehran. The poet divorced her husband in the mid-1950s, and she began writing in her home city. Her first collection, The Captive, appeared in 1955. The language in her work depicts images of both female agency and longing, and Farrokhzad’s words became immensely popular. She died tragically in a car accident when she was only 32-years-old, but her poetry, written originally in Persian, has remained an important voice through English translations dispersed across the globe. She is best known, perhaps, for her poem, “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season,” which begins like this:

And this is I

a woman alone

at the threshold of a cold season

at the beginning of understanding

the polluted existence of the earth

and the simple and sad pessimism of the sky

and the incapacity of these concrete hands.

After the Revolution

By the late 1970s, the Iranian Revolution resulted in Farrokhzad’s volumes being banned and the institution of the Ayatollah Khomeini. While the literary voices of women became suppressed under the fundamentalist regime, novelists of the diaspora began to remake the history of violence in the country and the ways in which women attain agency. Now living in Texas, the Iranian-born Farnoosh Moshiri has written novels, plays, and short stories that center on issues of gender equality in the midst of repression. Moshiri wrote for literary magazines in Tehran before the revolution, but she fled the country in 1983 with news of arrests of activists, intellectuals, and feminist writers. Her novel The Bathhouse (2001) depicts the resistance efforts of a group of women inside an Iranian prison.

Taking up a different point of view, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), a semi-autobiographical account of the writer’s upbringing in Tehran under the Ayatollah Khomeini, blends humor and tragedy to discuss the limits of feminism in contemporary Iran. Other autobiographical texts have also depicted the limits of individual freedoms—particularly for women—throughout Iran. In some cases, the very fact that these texts were published placed the writers’ lives in jeopardy.

Taking up a different point of view, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), a semi-autobiographical account of the writer’s upbringing in Tehran under the Ayatollah Khomeini, blends humor and tragedy to discuss the limits of feminism in contemporary Iran. Other autobiographical texts have also depicted the limits of individual freedoms—particularly for women—throughout Iran. In some cases, the very fact that these texts were published placed the writers’ lives in jeopardy.

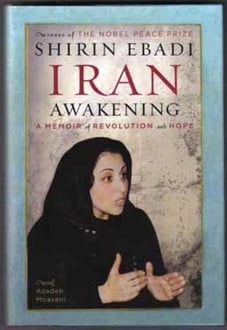

In 2007, Zarah Gharahramani’s My Life as a Traitor detailed the violence she and other women endured during sentences carried out in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. Like other writers of the diaspora, Gharahramani was born in Iran in the early 1980s. Given the risks she faced if she remained in the country, however, the writer managed to escape to Australia, where she currently lives. Shortly before Gharahrmani’s memoir was published, Shirin Ebadi, a notable Iranian human rights activist, judge, and lawyer, wrote her own account of life in the country. In Iran Awakening: A Memoir of Revolution and Hope (2006), Ebadi discusses her education, her role as one of the leading female lawyers in the country, and her persecution. After the book was published, Ebadi received death threats. She currently resides in London.

From works of poetry and fiction to memoirs that depict the very real struggles for gender and political equality, feminist literature from Iran makes up a significant component of contemporary world literature. Despite the limitations imposed by repression and political violence, discussions of female agency and power illuminate the real-world work that imaginative narratives can do.