While not necessarily as well known as Tom Clancy or Michael Crichton, Clive Cussler has for many years been one of the acknowledged masters of techno-fiction, a genre that blends science fiction, spy novels, and adventure stories. While someone like Crichton has become renowned for the realism and meticulous attention to detail that characterizes his works, Clive Cussler has made a name for himself over the course of more than 70 books by emphasizing the sort of swashbuckling, credulity-defying adventure that can be traced back to Robert Louis Stevenson and others. Here are five interesting facts about him.

1. He has uncovered more than 60 shipwrecks.

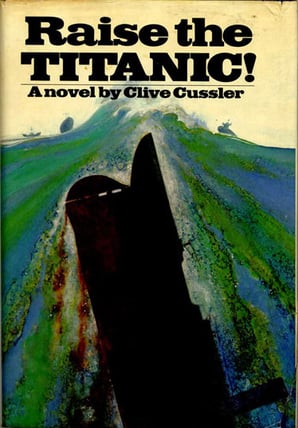

Cussler’s interest in maritime disasters will be apparent to anyone who has read his breakout novel Raise the Titanic! (1976). But his interest extends beyond the fictional, and it has led to his creation of the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA), a non-profit dedicated to discovering and studying shipwrecks. Its notable finds include the Carpathia, The Mary Celeste, and the Manassas.

2. His most famous character is named after his son.

At least, his first name. Not only was Dirk Cussler the namesake of Dirk Pitt (first seen in The Mediterranean Caper (1973)), the iconic marine engineer/hero of more than 20 novels, he has even followed in his father’s footsteps and co-written some Dirk Pitt novels himself.

3. His works have never been adapted well.

While Cussler’s peers, including Michael Crichton (1990's Jurassic Park) and Tom Clancy (1984's The Hunt for Red October), have frequently seen their work adapted for the screen with huge success, Cussler has not been so lucky. In fact, the 2005 adaptation of his 1992 novel Sahara was so poorly received that he was sued by the film studio that produced it. The studio claimed that the lack of box office success was due to misleading figures about the size of Cussler’s readership.

While Cussler’s peers, including Michael Crichton (1990's Jurassic Park) and Tom Clancy (1984's The Hunt for Red October), have frequently seen their work adapted for the screen with huge success, Cussler has not been so lucky. In fact, the 2005 adaptation of his 1992 novel Sahara was so poorly received that he was sued by the film studio that produced it. The studio claimed that the lack of box office success was due to misleading figures about the size of Cussler’s readership.

4. He holds a doctor of letters from SUNY Maritime College

In addition to his fiction, Clive Cussler has gained recognition for publishing nonfiction pertaining to his work with NUMA. His first such work, The Sea Hunters (1996), chronicled one of Cussler’s earliest restoration projects, the attempt to recover the wreckage of a well known revolutionary ship. While the salvage operation was ultimately a failure, the book was a great success—it was considered so meritorious that the State University of New York (SUNY) Maritime College accepted it lieu of a dissertation.

5. He likes to put himself in his novels.

Like the filmmaker Quentin Tarantino, or, perhaps more relevantly, beloved author Kurt Vonnegut, it’s not uncommon to find Cussler making a cameo in his own works. What began as a sort of joke during the writing of his 1990 novel Dragon took on a life of its own when Cussler’s editors neglected to remove his inclusion of himself as a minor character. Since then, his roles within his own work have grown more frequent and more significant, often involving the fictionalized Cussler providing his protagonist with a crucial piece of information at a climactic plot moment.