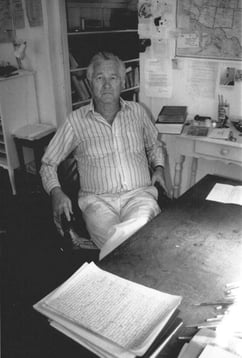

William Styron was born on May 11, 1925. An acclaimed American novelist and essayist well known for his works Sophie’s Choice (1979) and The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), Styron led a noteworthy life. He attended both Davidson College and Duke University, spent time abroad, and returned to the United States where he lived with his wife of over 50 years until his death in 2006. Here are five interesting facts that you may not know about William Styron.

1. He was fired from work at a publishing house.

After graduating from Duke University following a stint in the United States Marine Corps, William Styron moved to New York City at the urging of his professor, William Blackburn. There, he became a student of Hira Haydn who was teaching a creative writing class at the New School for Social Research. Along with his studies, Styron found a job at McGraw-Hill as a reader for the publishing house. Styron despised the position, and found himself fired only a few months into the job for his failure to project an appropriate work-man’s appearance and for slacking on the job. The New York Times reports that Styron rejected Thor Heyerdahl's ''Kon- Tiki,” which of course became a classic story. Styron used his time at McGraw-Hill in an autobiographical passage in Sophie’s Choice. His narrator in that novel, Stingo, who also works for a publishing house and makes the same error, reflects: “If McGraw-Hill had paid me more than ninety cents an hour, I might have been more sensitive to the nexus between good books and filthy lucre.”

After graduating from Duke University following a stint in the United States Marine Corps, William Styron moved to New York City at the urging of his professor, William Blackburn. There, he became a student of Hira Haydn who was teaching a creative writing class at the New School for Social Research. Along with his studies, Styron found a job at McGraw-Hill as a reader for the publishing house. Styron despised the position, and found himself fired only a few months into the job for his failure to project an appropriate work-man’s appearance and for slacking on the job. The New York Times reports that Styron rejected Thor Heyerdahl's ''Kon- Tiki,” which of course became a classic story. Styron used his time at McGraw-Hill in an autobiographical passage in Sophie’s Choice. His narrator in that novel, Stingo, who also works for a publishing house and makes the same error, reflects: “If McGraw-Hill had paid me more than ninety cents an hour, I might have been more sensitive to the nexus between good books and filthy lucre.”

2. He helped to found The Paris Review.

Styron’s travels abroad led him first to Paris where he met and worked with, among others, Peter Matthiessen and George Plimpton. The Paris Review was officially founded by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton, with Plimpton functioning as the journal’s editor from its inception in 1953 until his death in 2003. In the first issue of The Paris Review, Styron was the one who established its goal and purpose, saying in an editorial note:

“The Paris Review hopes to emphasize creative work—fiction and poetry—not to the exclusion of criticism, but with the aim in mind of merely removing criticism from the dominating place it holds in most literary magazines and putting it pretty much where it belongs, i.e., somewhere near the back of the book. I think The Paris Review should welcome these people into its pages: the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axe-grinders. So long as they're good.”

3. He fell in love in Rome after an interesting first date.

Styron’s first novel, Lie Down in Darkness, earned him the Prix de Rome of the Academy of Arts and Letters (the Rome Prize). This prize also entitled him to spend a year abroad for free, studying at the American Academy in Rome. Styron had to delay his year in Rome until after his military service concluded in 1952, and he first spent time in Paris before finally making it to Rome.

Once there, he fell in love with Rose Burgunder, a poet who was also studying at the American Academy at the time. The two married in Rome in 1953. When asked in an interview with the Boston Globe whether or not the pair talked about books on their first date, Rose provided an amusing anecdote. It turns out she was talking with Styron, Truman Capote, and another person when the discussion turned to Lie Down in Darkness. Rose chimed in saying, “Oh, what a wonderful novel,” even though she had never read it. Styron asked her to go out with him the next night. She said:

"The next day I went all over Rome looking for a copy of his book so that I could read it before our date. All I could find was a copy at a library in Rome as it was closing, which I grabbed quickly. Back then all the books there had opaque covers that were clear over the spines so you could see just the title clearly. When I got home I read a couple of chapters and thought, “Uh-oh, not very good,” and I put it down. When I picked it up the next day I saw that it was the right title, but not the right author. It wasn’t Bill’s book. When I went out with him that night I had to explain myself, and we laughed about it. He gave me a copy and, of course, I loved it."

4. He’s the namesake of a particular three acres of green space.

Speaking of Lie Down in Darkness, the fictional setting of the story, Port Warwick, is now a real place in Newport News, Virginia, Styron’s hometown. Indeed, the city paid homage to its native son, not only in naming a development Port Warwick, but also in naming a three acre plot of land after the author. William Styron Square is set in the center of Port Warwick and is considered its crowning feature. Likewise, two streets which go forth from the square are named after Styron’s characters: Loftis Boulevard and Nat Turner Boulevard.

Styron was also asked to name the rest of the streets and parks in Port Warwick. He chose to pay tribute to some of his favorite American writers—including Philip Roth. When describing how he went about picking names, he said:

“These artists seem to me ones who are indisputably lodged in the pantheon of American literature. Limitation in number has forced me to exclude many illustrious writers deserving of recognition; therefore my choices reflect a personal leaning. But the overall selection of names does, I think, represent the best in the great flowering of American literary art.”

5. His works are both well-loved and fraught with controversy.

Perhaps Styron’s two most well-known works are also two of his most controversial. He published The Confessions of Nat Turner in 1967. The story, which uses as its protagonist the historical figure of Nat Turner, was praised by some notable black writers of the day including Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin but also met with much disdain by legions of African Americans who felt Styron portrayed Nat Turner as scattered and apathetic about the whole situation.

Perhaps Styron’s two most well-known works are also two of his most controversial. He published The Confessions of Nat Turner in 1967. The story, which uses as its protagonist the historical figure of Nat Turner, was praised by some notable black writers of the day including Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin but also met with much disdain by legions of African Americans who felt Styron portrayed Nat Turner as scattered and apathetic about the whole situation.

Critics also cited Styron’s positive portrayal of slave-owners as further reason for their disapproval. Other issues were taken with the novel, and a group of ten prominent African American scholars joined forces to publish essays in response to the novel. These essays were collected in William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, published in 1968. Despite that, The Confessions of Nat Turner won the coveted Pulitzer Prize in 1968.

Sophie’s Choice, perhaps Styron’s most well-known work, met with its fair share of resistance due in large part to the portrayal of Sophie, a Catholic Christian, as the main character and a sufferer in the Holocaust. Sylvie Mathé, in her essay The ‘grey zone’ in William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, (wherein she goes on to cite other scholars like Alvin Rosefeld) argues that by presenting Sophie and her trials at the hands of the Nazis, Styron—although mentioning the plight of the Jewish people—attempts to shift the discussion of the Holocaust and the horrors of the concentration camps away from what was done to the Jewish population in particular and instead make it into a more general discussion about evil.

In other words, by showing how a Christian was affected by the evils of the Holocaust, Styron essentially alleviates any sense of Christian guilt and washes over the fact that Christian anti-Semitism was part of the cause for the Holocaust, and in effect he “contribute[s] to a blurring of historical causes and an indifferentiation in assessment that partake of a form of grey zone.”

Sophie’s Choice went on to be adapted into a celebrated film in 1982. Meryl Streep, who starred as Sophie, won an Academy Award for Best Actress.

Sources: William Styron Image, Boston Globe, New York Times, Portwarwick.com, Biography.com, The Paris Review, Cairn.info