Storing books standing on their edges is a relatively new practice. The most common storage prior to the 16th century was to pile them horizontally with the fore-edge facing out. The fore-edge is the edge opposite the spine of the book. Identification issues were resolved by marking the books with a design on this edge or writing the book's title there.

But by the end of the 16th century there were so many books in libraries that a new system of shelving was required. This is when the method of standing books on end with spines facing out was implemented. Now binders could use the edges to beautify the book, limited only by their imagination. Embellishment was not the only purpose however, the various fore-edge decorations also protected the book's contents from dust, moisture, and handling.

Gilding

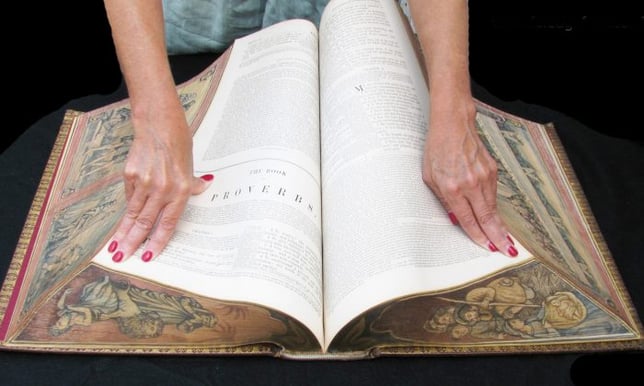

Applying gold in powder or a thin sheet to an object, in this case a book's pages or cover boards, is a very old art.

The gold was often mixed, or alloyed, with other metals like silver or copper. Some cheaper editions used less expensive gold paint which would dull comparatively quickly. At the other end of the spectrum is pure 22kt gold being used for gilding.

The page edges of antiquarian books may shine with gold. It can be just the top edges or it can also include the front and bottom edges. Top edge gilt is sometimes referred to as TEG or T.E.G. and all edge gilt is referred to as AEG or A.E.G.

It is beautiful and does serve a practical purpose. When applied in conjunction with glue it protects the page edges from the effects of age (turning brown), moisture, and dust. They still need to be treated with care as they are easy to scratch and susceptible to physical damage.

Gilt edges are only present on books where there is a smooth application surface and therefore never on books with deckled edges. Individual pages may also be gilded. These are referred to as being ‘illuminated.’

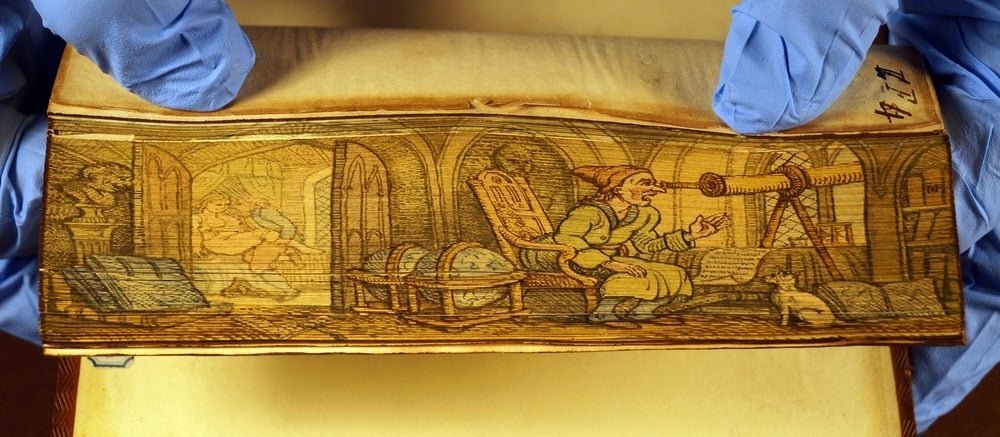

Single Fore-Edge Painting

Where gilding has a practical purpose in protecting the book's pages from moisture and browning, fore-edge painting is done for beautification. The fore-edge is not the spine, the top, or the bottom of the book, but is the outside edge you would see and use to thumb through the book.

A cousin of the Renaissance painter Titian named Cesare Vecellio began to use the fore-edge of books as a canvas around the 16th century. These paintings were applied directly to the edges of the leaves, visible to anyone who looked when the book was closed.

A group of skilled English bookbinders during the Restoration known as the Queen's Binders took this skill a step further in the 17th century. They started painting on the slight inner edges of the pages and then gilded or marbled the outside page edges. The scene would then be undetectable when the book was closed and only revealed when the pages were fanned slightly.

They had created disappearing and reappearing masterpieces. Books with this type of fore-edge painting require a special stand for display that keeps the pages at the proper angle to enable seeing the art.

Double Fore-Edge Painting

This is where a book's fore-edge shows one picture if the pages are fanned back to front, and a different picture if they're fanned front to back. Some artists opt to include a third picture on the very edges of the eaves rather than gilt or marbling. This becomes a triple fore-edge painting. Painters have also embellished the top and bottom edges of the book pages, an effect known as a panoramic fore-edge painting.

A fair number of books sold today with fore-edge paintings are antiquarian volumes where the edge paintings were added much later. Fore-edge paintings are believed to have originated as long ago as the 10th century. Initially the fore-edge paintings depicted things like shields or coats of arms. As the interest in beautification grew the paintings came to include landscapes, religious iconography, and floral designs. Sometimes the paintings were related to the book's subject matter and sometimes they were not.

Gauffering

This practice is likely as old as edge-gilding. Gauffering involved impressing a pattern into the edges of a book after they had been gilded, using warmed finishing tools or rolls. This labor-intensive form of decoration never became common, and by the mid-1600s it had mostly died out. The practice resurfaced in the 19th century with ornate and religious bindings showing a variety of lace-like patterns.

Edge Marbling

Although most common in the 19th century, examples of marbled edges can be found on leather bindings in the 17th century. Patterns were expected to match the design of the endpapers but otherwise were generally at the binder's discretion.

There were three methods for edge marbling: the traditional process that placed the edge of the book on a tray of colors, the transfer of patterns from already existing marbled papers, and just the use of a roller.

All of the above-described techniques served a real purpose in that they protected the pages of the books from damage. They also provided incredibly detailed works of art to enhance the enjoyment provided by the books themselves.