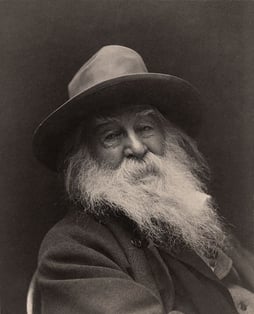

When Walt Whitman published the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, it contained just twelve poems. He fronted the money for the publication himself and almost no copies were sold. The now-iconic photo of young, jaunty-hatted Whitman that served in place of the author’s name cast an odd shadow over what were already terribly peculiar poems. At best, the volume of billowing, exuberant free-verse was considered a curiosity. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for instance, appreciated its attempt to revive the spirit of transcendentalism, but found the verse itself a bit loose. At worst, the collection was thought of as an abomination. Poet John Greenleaf Whittier was said to have thrown his copy into a fire. Boston’s District Attorney found the book to be obscene and attempted to suppress it. It even cost Whitman his job after the Secretary of the Interior read it and deemed it offensive.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Leaves of Grass. It is perhaps more difficult to sing its praises without retreading old ground. Many contemporary poets and scholars hold that all American poets can trace their artistic lineage directly back to either Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman. And to wit, many of America’s greatest poets have written about or in direct response to Whitman’s poetry, from Langston Hughes to Ezra Pound to Allen Ginsberg. When Harold Bloom said, in a preface to the sesquicentennial edition of Leaves of Grass, that it could be the “secular scripture of the United States,” he hardly exaggerated. Where one can, at this point, largely take the overwhelming greatness and influence of this volume for granted, the rate at which its greatness came to be recognized is interesting.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of Leaves of Grass. It is perhaps more difficult to sing its praises without retreading old ground. Many contemporary poets and scholars hold that all American poets can trace their artistic lineage directly back to either Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman. And to wit, many of America’s greatest poets have written about or in direct response to Whitman’s poetry, from Langston Hughes to Ezra Pound to Allen Ginsberg. When Harold Bloom said, in a preface to the sesquicentennial edition of Leaves of Grass, that it could be the “secular scripture of the United States,” he hardly exaggerated. Where one can, at this point, largely take the overwhelming greatness and influence of this volume for granted, the rate at which its greatness came to be recognized is interesting.

By the time of his death, Walt Whitman had grown Leaves of Grass from a slight, 90-odd page volume into a gargantuan tome, almost biblical in its size and scope. He was perpetually in the process of revising the text, putting out between six and nine (depending on who you ask) editions of it in his lifetime. In 1892, he put out his ‘Deathbed Edition,’ which included more than 400 poems. By this time Whitman’s greatness was well established, as was the greatness of his signature volume.

Whitman earned quite a reputation. 1885 saw the formation of the Boston Whitman Fellowship (a group known for celebrating Whitman’s birthday each year), but long before then, his esteem earned him a literary correspondence and friendship with Bram Stoker (who allegedly based the titular character in 1897's Dracula on Whitman), a sickbed visit from Oscar Wilde, and an unshakeable hold on the American imagination.

Interestingly, in the first issue of long-running magazine The Nation, a young Henry James vehemently panned Whitman’s post-bellum collection Drum Taps (1865). He called it “the effort of an essentially prosaic mind to lift itself, by a prolonged muscular strain, into poetry.” Within his own lifetime, however, James would come to regret the review as deeply misguided. Henry James hardly seems like a man who is easily converted to new ideas, but the cultural force of Whitman’s poetry was simply not to be ignored.

Where once Leaves of Grass was thought of as merely a curiosity, its meteoric ascent proved so powerful as to not only rid itself of that label but to cause documents by the likes of Henry James and John Greenleaf Whittier to become curiosities themselves.

Where once Leaves of Grass was thought of as merely a curiosity, its meteoric ascent proved so powerful as to not only rid itself of that label but to cause documents by the likes of Henry James and John Greenleaf Whittier to become curiosities themselves.

The painstaking, poem-by-poem growth of Leaves of Grass is remarkable. That Leaves of Grass, growing and alive, evolved in public perception from obscene oddity to masterwork of American poetry all within the lifetime of the poet himself speaks volumes about the power of Whitman’s verse. Walt Whitman believed in a sort of mutual absorption between a poet and his country. With regard to his own volumes that may hold some truth. Leaves of Grass ultimately took on a poetic mass so great that it could hardly be anything but the center of its own literary universe.