Like Walt Whitman, Guillaume Apollinaire contains multitudes. While he is largely known to English speaking readers as a important modernist poet, he was also a noted art critic and a writer of novels and plays. And while his poetic imagination was best displayed in his actual poems, one can’t help but wonder if it was also at work when it came to his success in that most fickle of businesses: the naming of artistic movements.

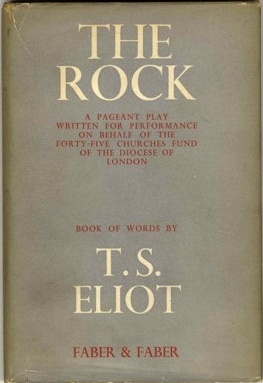

Apollinaire was born in Rome to Polish aristocrats, but he moved to Paris as a young man. There, he quickly became a prominent player in the city's early 20th century art scene. He befriended (and sometimes collaborated with) such luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, Max Jacob, and Andre Breton while developing his own skills as a poet. Perhaps his most famous poem, "Zone" (1913), would help set the stage for both the Anglophone modernists and later Beat poets like Frank O’Hara. Though it was set in loose rhyming couplets, the poem was keen to play by its own formal rules, using minimal punctuation and constantly shifting pronouns to turn modern objects like the Eifel Tower and the first airplane into almost pastoral poetical subjects, anticipating the feel of later works like T.S. Eliot’s "The Wasteland" (1922) and O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964) while helping to usher in the wave of French surrealist poets.

Apollinaire was born in Rome to Polish aristocrats, but he moved to Paris as a young man. There, he quickly became a prominent player in the city's early 20th century art scene. He befriended (and sometimes collaborated with) such luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, Max Jacob, and Andre Breton while developing his own skills as a poet. Perhaps his most famous poem, "Zone" (1913), would help set the stage for both the Anglophone modernists and later Beat poets like Frank O’Hara. Though it was set in loose rhyming couplets, the poem was keen to play by its own formal rules, using minimal punctuation and constantly shifting pronouns to turn modern objects like the Eifel Tower and the first airplane into almost pastoral poetical subjects, anticipating the feel of later works like T.S. Eliot’s "The Wasteland" (1922) and O’Hara’s Lunch Poems (1964) while helping to usher in the wave of French surrealist poets.

Sadly, just a few years after publishing Alcools (the 1913 collection in which "Zone" appears), Apollinaire would suffer a shrapnel wound to the head while fighting in World War I, dying soon after of the Spanish Flu.

But while Apollinaire’s contributions to poetry are undeniable, his contributions to the art world are likely to be equally long-lasting. Why? Because he’s the one who coined the terms ‘Cubism’ and ‘Surrealism’.

Around 1910, Jean Metzinger painted a portrait of Apollinaire (the first of many of the poet) using the style that artists like Picasso and Georges Braque would become known for, which was one of the first works of art to be described as Cubist. In the following years, Apollinaire would champion Cubism to the world, heralding it as the newest manifestation of high art. In 1912, he would coin the term 'Orphism' to refer to the works of Robert Delaunay and František Kupka. Orphism may not be a household term in the way that Cubism is, but it is still a major contribution to artistic nomenclature.

Around 1910, Jean Metzinger painted a portrait of Apollinaire (the first of many of the poet) using the style that artists like Picasso and Georges Braque would become known for, which was one of the first works of art to be described as Cubist. In the following years, Apollinaire would champion Cubism to the world, heralding it as the newest manifestation of high art. In 1912, he would coin the term 'Orphism' to refer to the works of Robert Delaunay and František Kupka. Orphism may not be a household term in the way that Cubism is, but it is still a major contribution to artistic nomenclature.

Just a few years later, after seeing Erik Satie’s ballet Parade (1917), Apollinaire gave the Surrealist movement its name (as well as a poetic manifesto extolling its virtues). In the end, despite his untimely death, Apollinaire managed to name three of the most important artistic movements of the 20th century. Not bad for 38 years’ work.

This is not to suggest that Apollinaire’s only contribution to the art world was coining new names. He was a fervent advocate for Cubism’s recognition by the art world and once even called for the Louvre to be burned down. Given this last fact, it’s little wonder that when the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, Apollinaire was one of the first people detained by the police (as was Picasso). Although he had not committed the crime (the painting was later revealed to have been stolen by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian Louvre employee who may have been trying to reclaim the painting for Italy), it turned out that his former secretary had, around the same time, stolen three Egyptian statuettes from the museum. Apparently Guillaume Apollinaire’s was so central to the Parisian art scene that he was even tangentially linked to its crime.