On May 12 each year, the international poetry community stops to recognize a quirky, off-kilter poetic form: the limerick. Celebrated on the birthday of English artist, illustrator, and poet Edward Lear (1812-1888), the holiday pays tribute to the five-line, rhyming form and to Lear himself, who helped popularize the form throughout his career.

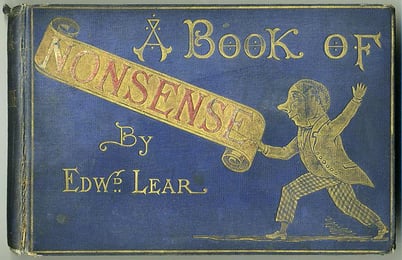

Though it’s common knowledge the limerick was in existence long before Lear’s time—some scholars contend the form first appeared in England as early as the 18th Century—Lear’s use of nonsensical poetics vaulted the form into prominence, especially following the 1846 publication of Lear’s collection of limericks, A Book of Nonsense.

Though it’s common knowledge the limerick was in existence long before Lear’s time—some scholars contend the form first appeared in England as early as the 18th Century—Lear’s use of nonsensical poetics vaulted the form into prominence, especially following the 1846 publication of Lear’s collection of limericks, A Book of Nonsense.

To say Lear was something of an eccentric would be an understatement, and to say the limerick is something of an eccentric poetic form would also be downplaying its qualities. So perhaps it makes perfect sense why Lear and the limerick will be forever linked in the hearts and minds of poetry lovers the world over.

About Lear

Lear was the 20th child born to the Lear family—yes, that’s right, the 20th—and the youngest to survive. He was born to the family of stockbroker Jeremiah Lear on May 12, 1812. In part due to the size of the family, Lear was raised by his siblings, primarily an older sister, who scholars believe was key in introducing him to the wonders of the written word, poetry in particular.

Though Lear received little to no formal education throughout his childhood and adolescence, he had a natural aptitude for drawing and sketching, selecting animals and landscapes as his main subjects. His high-degree of talent and skill as an illustrator led to low-paying work as a professional artist and even an invitation from Queen Victoria for a series of sketching and drawing lessons.

Lear published two volumes of illustrations prior to beginning his literary career. His debut book, A Book of Nonsense, was published in 1846 and consisted of more than 100 limericks focused heavily on real and imagined imagery and the auditory pleasure of unusual or interesting word combinations. The book received wide critical acclaim and a devoted readership, prompting three additional printings to meet reader demand.

Lear published two volumes of illustrations prior to beginning his literary career. His debut book, A Book of Nonsense, was published in 1846 and consisted of more than 100 limericks focused heavily on real and imagined imagery and the auditory pleasure of unusual or interesting word combinations. The book received wide critical acclaim and a devoted readership, prompting three additional printings to meet reader demand.

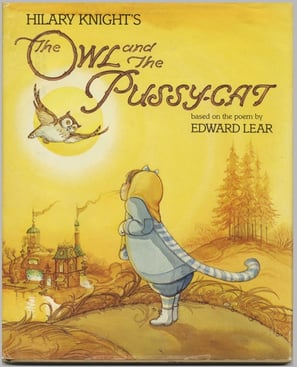

In 1870, Lear published another volume of limericks titled Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets, which included his most famous nonsense song, The Owl and the Pussycat.

Despite a life plagued by serious health issues, including seizures, asthma, and chronic depression, Lear continued to write and publish collections of limericks—212 published limericks in total—until his death in 1888.

The Limerick

Traditionally composed in five rhyming lines and adhering to an AABBA rhyme scheme or structure—though variations and mutations certainly exist—limericks are often humorous in nature and can contain jarring, nonsensical images, similes, and metaphors, almost verging on a version of absurdism. Most limericks are composed in anapestic meter with the fourth and fifth lines shorter and more concise than the ones that preceded it. Limericks often address more bawdy subject matter, though traditional limericks eschewed the bawdy in favor of calling out taboos of the time, both social and otherwise.

Though widely considered common characteristics before Lear began working with the form, literary scholars largely credit Lear for cementing these qualities of the form and popularizing the limerick as an easily accessible, more oral poetic style.

Though the style fell out of mass popularity in the 19th and 20th Centuries, some of the literary world’s most renowned poets and writers continued to dabble in limericks as a way of flexing their creative muscles.

Though the style fell out of mass popularity in the 19th and 20th Centuries, some of the literary world’s most renowned poets and writers continued to dabble in limericks as a way of flexing their creative muscles.

For your reading pleasure, here are a handful of examples of the style from Lear himself, poet Ogden Nash, and Rudyard Kipling:

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, 'It is just as I feared!

Two Owls and a Hen,

Four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!'

-Edward Lear

A wonderful bird is the pelican

His bill can hold more than his beli-can

He take in his beak

Food enough for a week

But I’ll still be damned if I see how the heli-can

-Ogden Nash

There was a small boy of Quebec

Who was buried in the snow up to his neck

When they said, “Are you friz,”

He replied, “Yes, I is”

But we don’t call this cold in Quebec.

-Rudyard Kipling