Born on October 29, 1740 James Boswell is best remembered for his momentous Life of Johnson. Often regarded as the most important biography written in the English language, Boswell's masterpiece is certainly an incredible contribution to the world of literature and books. But during his own lifetime, Boswell was much better known for another contribution: his role in the establishment of new copyright law for the United Kingdom.

Common Law Copyright

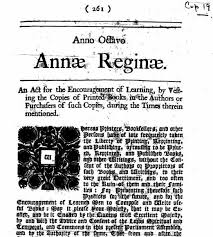

The first copyright law in England was passed in 1710 during Queen Anne's reign. Parliament granted a fourteen-year term of copyright, renewable once if the author was still alive at the end of the term. There  was a separate grandfather clause of 21 years for books already published. At the time, copyrights were held not by authors, but by publishers and booksellers. They were less than thrilled with this new law because they'd always presumed perpetual copyright under common law. Booksellers and publishers banded together to appeal the law, but Parliament declined to reverse their decision. Unsatisfied, booksellers decided to turn to the courts. They filed a collusive lawsuit, Tomson v Collins, which the court promptly threw out.

was a separate grandfather clause of 21 years for books already published. At the time, copyrights were held not by authors, but by publishers and booksellers. They were less than thrilled with this new law because they'd always presumed perpetual copyright under common law. Booksellers and publishers banded together to appeal the law, but Parliament declined to reverse their decision. Unsatisfied, booksellers decided to turn to the courts. They filed a collusive lawsuit, Tomson v Collins, which the court promptly threw out.

Then in 1769, they managed a real lawsuit. In Millar v Taylor, the plaintiffs alleged that James Thomson's copyright on Robert Taylor's poem "The Seasons" had been infringed upon. Lord Mansfield, the chief judge in the case, had previously represented the booksellers, a factor that probably played no small part in the booksellers' getting a favorable judgment. An appeal was brought before the House of Lords, and the booksellers opted to settle rather than risk an unfavorable decision. It seemed that the booksellers had won their perpetual copyright after all.

Donaldson Takes a Stand

The impact of the Millar v Taylor ruling was that a few powerful booksellers coulc continue to monopolize the trade. While unauthorized and pirated editions certainly appeared, the Stationer's Company kept a close eye on publishers and booksellers, and they would take legal action against those who dared to publish their own editions. One such bookseller was Alexander Donaldson. Born in Edinburgh in 1727, Donaldson opened a bookshop there in 1748. In the early 1760's, he and his older brother, John, moved to London and set up shop there. They mostly sold cheap paperbacks published in London and Edinburgh.

London publishers came after Donaldson in 1773, claiming that he was infringing on the copyrights of varioius publishers. Donaldson argued that he mostly offered cheap editions of English classics that were no longer protected under the Copyright Act because they were published too long before. He'd been making great profits off his business and refused to stop. He ended up in court, in the famous case Hinton v Donaldson.

Donaldson chose James Boswell, a friend from the literary world, to represent him. Boswell argued that London publishers' "perpetual exclusive property" of books would create a monopoly and ultimately raise prices. Boswell and Donaldson won the case, and the notion of perpetual copyright was officially overturned. He was so encouraged by his victory, he decided to go one step further and undo perpetual copyright once and for all by getting the courts to reverse their 1769 decision. Donaldson sued another bookseller named Beckett for the right to publish Thomas Stackhouse's New History of the Bible.

Donaldson chose James Boswell, a friend from the literary world, to represent him. Boswell argued that London publishers' "perpetual exclusive property" of books would create a monopoly and ultimately raise prices. Boswell and Donaldson won the case, and the notion of perpetual copyright was officially overturned. He was so encouraged by his victory, he decided to go one step further and undo perpetual copyright once and for all by getting the courts to reverse their 1769 decision. Donaldson sued another bookseller named Beckett for the right to publish Thomas Stackhouse's New History of the Bible.

Boswell as Legal Propagandist

Unfortunately, Boswell could not represent Donaldson in this second case because he was back in Edinburgh. So he found another way to support Donaldson. Boswell had successfully used political propaganda to sway the Parliament in the Douglas cause: he'd published everything he could find about the case, effectively swaying public opinion--and the opinion of those in Parliament. Now Boswell took a similar approach.

On August 3, 1773, an article appeared in the London Chronicle. Most likely penned by Boswell, the article brings attention to the first Donaldson case, noting that "all the Literati of Europe [is] naturally interested in a question so much connected with learning." Then on February 2, 1774, just before Parliament was scheduled to hear arguments in Donaldson v Beckett, Boswell published The Decision of the Court of Session upon the Question of Literary Property. The publication had its desired effect and undoubtedly contributed to the judges' reversal of their 1769 decision.

Outright Rejection of Perpetual Copyright

The court ruled in favor of Donaldson. One judge, Lord Camden, was particularly scathing toward booksellers: "The arguments attempted to be maintained on the side of the respondents, were founded on patents, privileges, and Star Chamber decrees and bye (sic) the laws of the Stationer's Company; all of them the effects of the grossest tyranny and usurpation: the very last places in which I should have dreamed of finding the least trace of the common law of this kingdom." Thus Lord Camden and a number of his cohorts summarily denied that common law copyright had ever existed.

The decision was met with joy all over the United Kingdom. Robert Forbes, Bishop of Ross and Caithness, wrote in his journal on February 26, 1774 that when news of the decision reached Scotland, there was "great rejoicing in Ediburgh upon victory over literary property: bonfires and illuminations; ordered tho' by a mob, with drums and two fifes."

Later that year, UK booksllers sought to extend their statutory copyright with the Bookseller's Bill. It passed the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords. Today, the outcome of Donaldson v Beckett remains the basis for UK copyright law. In 1834, the United States Supreme Court essentially followed suit in its decision for Wheaton v Peters, rejecting perpetual copyright and opting for the statutory instrument that remains in place today. James Boswell, then, is not only one of the greatest biographers of all time, but also a key figure in the history of copyright law.