The paperback has been around since the Civil War, but it wasn’t until steam-powered printing presses and the growing technology that impacted the ability to produce, transport, and sell cheaper versions of heavier hardbacked bound volumes that the paperback truly began to impact the way Americans read and how they viewed the world. With the opportunity to read more, write more, and experience direct variety in our reading habits, the paperback caused a small revolution. To witness it, you’d only have to look as far as the new revolving book stands at the local drug store. So what are three major ways the paperback book changed American culture?

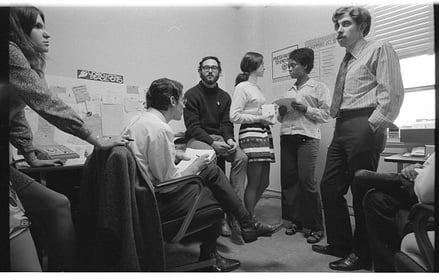

1. Contributed to the Social Unrest of the 1960s

In 1935, Penguin Books in Great Britain released Andre Maurois’ Ariel in paperback form. This move was the brainchild of Allen Lane, one of the founders of Penguin Books, who self-invested in the venture to bring inexpensive books to the masses. Booksellers seeing the low price, high volume nature of paperbacks were reluctant to carry Penguin Books in this new format. However, Lane looked to alternate sources for distribution and found that Woolworth’s was more than happy to stock their shelves with the low-priced tomes. When booksellers saw the cheap volumes flying off shelves, they followed suit.

America’s counterpart to Allen Lane, Robert de Graaf, created his own line of paperbacks “Pocket Books” and added some flare with illustrated covers. Not satisfied with only wooing booksellers, de Graaf went a step further and utilized magazine and news-stands, as well as small shops to carry the mass produced copies. He didn’t skimp on marketing, either. A New York Times full page ad declared that this move would “Transform New York’s reading habits” and it wasn’t wrong. Priced at 25 cents, anyone—not just those with access to academic libraries, and not just those with expendable income, and not just those with prior access to literary materials—could pick up classics and intellectual works along with their morning coffee and cigarettes. Enter the self-taught, turned on, and dropped out youth of the 1960s. As they encountered the materials and ideas that had been long denied them because of class and economy, their anger and displacency grew until there was general social unrest and demand for a breakdown in the class system and greater access to education and free ideas.

2. Gave Struggling Writers and Artists the Opportunity to Reach an Audience

A paperback used to be a reprint of an already released and known hardback edition. One could choose to purchase a hardcover copy, or wait and get a (usually) identical reading experience in a soft copy for a fraction of the price. However, in the mid-20th century there came an idea as revolutionary as Netflix original programing: Fawcett Publications introduced original paperback books. These were titles never before released in hardcover and never intended for hardcover. They were released only in paperback form. Now, for the cost of a little more than a magazine, you could have a whole book to while away hours on the train or after work. As people stopped buying magazines and invested instead in books, the writers who had been paying rent writing an article here and there could be contracted to finally write their novel and have it on shelves in bound form.

A paperback used to be a reprint of an already released and known hardback edition. One could choose to purchase a hardcover copy, or wait and get a (usually) identical reading experience in a soft copy for a fraction of the price. However, in the mid-20th century there came an idea as revolutionary as Netflix original programing: Fawcett Publications introduced original paperback books. These were titles never before released in hardcover and never intended for hardcover. They were released only in paperback form. Now, for the cost of a little more than a magazine, you could have a whole book to while away hours on the train or after work. As people stopped buying magazines and invested instead in books, the writers who had been paying rent writing an article here and there could be contracted to finally write their novel and have it on shelves in bound form.

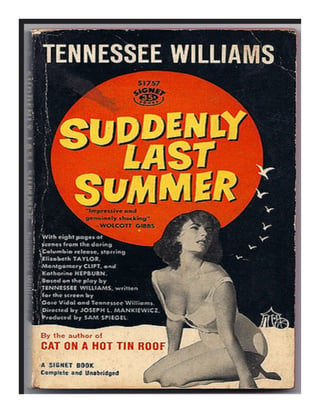

Likewise with the cover art. Those pulp artists who had been lending their talents to cheap magazines found that they could be just as easily hired to design covers for Of Mice and Men instead of Man’s Life Monthly. The smaller size and reduced exposure meant that the illustration had to be twice as eye catching as a magazine cover. Not only did the covers impact the sale of the book, they often outshined the content housed within it. The collectible nature of these volumes continues to be based on the cover of the edition rather than the book itself.

3. Created Science Fiction as We Now Know It

Science fiction was a genre known only to those who read the small number of magazines that printed science fiction. Ian Ballantine, hired by Allen Lane to produce paperbacks in the U.S., changed all of that.

Science fiction was a genre known only to those who read the small number of magazines that printed science fiction. Ian Ballantine, hired by Allen Lane to produce paperbacks in the U.S., changed all of that.

After being forced out of Penguin and fired by Bantam, he founded Ballantine Books and began releasing both hardcover and paperback versions of the same books at the same time. Part of their marketing and distribution strategy was to focus on genre-specific areas, which included science fiction. Ray Bradbury’s classic, Fahrenheit 451, about a dystopian culture that made reading books illegal was the first recognized success of this new market.

Pocketbooks had their own hook into the weird side-genre known as science fiction. With authors like H.G. Wells and Theodore Sturgeon, the publisher would release digest compilations of stories, but Donald Wollheim, the editor and Futurian for the company had bigger ideas. He began Ace Books which released two short novels in one volume, a bargain for the burgeoning science fiction customer base.

The form itself also made a significant, if not somewhat subtle change. Longer science fiction works had been published, but in serial form. Each chapter, or section, had to stand alone and be read by a reader who may not have read the previous or following installment. With the invitation to write complete novels to be read as a singular and complete work, writers changed their form, narrative, and story-telling style to reflect that change in readership.

This way of reading, of buying, of publishing, has quietly made some significant marks on how we receive and collect knowledge, art, and ideas. While it has found a place in our culture, the ways in which it has changed and shaped our reading habits is truly fascinating. Who knew so much could be accomplished with some cheaper glue, more fragile binding, and a soft cover?

Sources:

-Trikosko, M. S. (n.d.). Young men and women committee members in an office planning demonstrations as part of the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam which took place on October 15, 1969 [Photograph]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. InLibrary of Congress. Retrieved May 26, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 1969, October 1)

-Wyatt, E. (2006, May 22). Literary Novels Going Straight to Paperback. New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2016, here.

-Paperback. (2016, May 9). Retrieved May 18, 2016, from here.

-Shaffer, A. (2014, April 9). How Paperbacks Transformed the Way Americans Read. Mental_Floss. Retrieved May 18, 2016, here.

-Liptak, A. (2015, January 15). The Rise of the Paperback Novel. Kirkus Review. Retrieved May 18, 2016, here.

-Von Schack, C. (2009, August 30). Suddenly Last Summer [Photograph found in Flickr]. In Flickr.com. Retrieved May 26, 2016, here. (Originally photographed 2009, August 30)