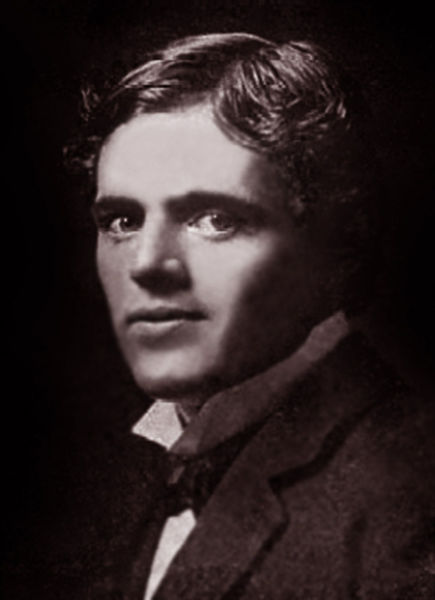

America has a long history of great writers, but a rather shorter history of paying them. Herman Melville, not unlike Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, died with practically no money from his work. One of the first people to make a writer’s living in this country was Jack London. Most famous for his novel, The Call of the Wild, London was a diverse writer, and he was decidedly prudent in aligning himself with America’s booming periodical industry.

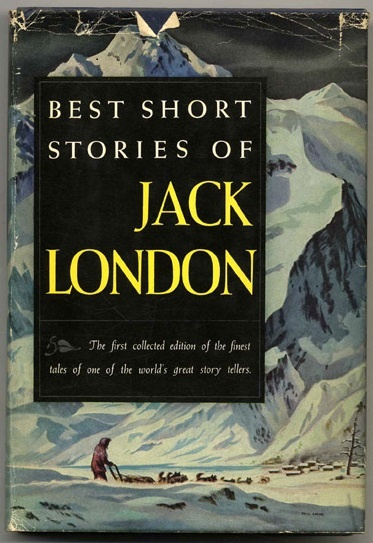

When Jack London began his literary career around 1900, he was far from the first writer to embrace the opportunities provided by magazines. Some of the great 19th century novels, like Dickens’ Bleak House and Tolstoy’s War and Peace, were first introduced to the world in serial. What distinguishes London amid an already robust tradition was his pragmatism and versatility. Magazines demanded a variety of writing, and Jack London saw an opportunity to make a living off of them by being equally diverse. Not only did he write fiction, he wrote humorous sketches, poetry, war correspondence, and he reported on some of the biggest news of his day, including an evocative account of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

When Jack London began his literary career around 1900, he was far from the first writer to embrace the opportunities provided by magazines. Some of the great 19th century novels, like Dickens’ Bleak House and Tolstoy’s War and Peace, were first introduced to the world in serial. What distinguishes London amid an already robust tradition was his pragmatism and versatility. Magazines demanded a variety of writing, and Jack London saw an opportunity to make a living off of them by being equally diverse. Not only did he write fiction, he wrote humorous sketches, poetry, war correspondence, and he reported on some of the biggest news of his day, including an evocative account of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Jack London might never have had this voracity for writing if not for his impoverished environment. Always smart and inquisitive, a series of odd jobs and expenses delayed his entrance to high school to age 19, and going to college was only made possible by a loan from the owner of a tavern where he frequently read. However, his sense of adventure was not incongruous with his writing. As a creator of characters who are often in dire survival situations, struggling against nature’s hostilities, it might not be surprising that London himself was a daring soul. Among his most dramatic exploits was a trip to the Klondike in search of gold, during which he endured terrible hunger, and contracted scurvy, causing him to lose four of his teeth.

When London was in his full creative swing, he made an ample living from writing, which would today be worth a salary in the high five figures. His willingness to write knew no bounds, and he welcomed projects that put him in considerable danger. He was assigned in 1904 to report on the Russo-Japanese War, and arrived in Japan in January of that year. This period was a tumultuous one for London. He was arrested by the Japanese soon after arrival. He then moved to Korea, where he was arrested again for being too close to the Chinese border. He was released, but was soon detained again for fighting with the soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army, whom he claimed stole feed for his horse. His assignment finally ended six months later, after being released with the help of President Theodore Roosevelt.

London left behind a considerable oeuvre, one which even the most dedicated fans would be hard-pressed to read in entirety. What complicates the endeavor is that a good deal of London’s work was published without his name, or has since been lost. In 2015, a piece written by London* in 1903 was unearthed in the archives at the University of Texas at Austin. The essay was published in a periodical named The Editor, and advises aspiring writers how to begin making money from writing, starting from scratch.

London admits he went into the magazine world entirely blind. He did not know any other writers, nor any example of a successful one. How to get writing in print was a mystery to him, and he spent months sending in manuscripts any place he could, only to receive a trove of rejection slips. This process went on for long, and happened so swiftly that London refused to believe a human, rather than a machine, could read and dismiss his writings with such speed. Eventually, London had his breakthrough, and an editor who was willing to pay him $40 for his 4,000 word short story, “A Thousand Deaths.” This anecdote is surely a relief to anyone who knows the maddening silence of early creativity, but London provides some useful advice useful to any writer employ:

London admits he went into the magazine world entirely blind. He did not know any other writers, nor any example of a successful one. How to get writing in print was a mystery to him, and he spent months sending in manuscripts any place he could, only to receive a trove of rejection slips. This process went on for long, and happened so swiftly that London refused to believe a human, rather than a machine, could read and dismiss his writings with such speed. Eventually, London had his breakthrough, and an editor who was willing to pay him $40 for his 4,000 word short story, “A Thousand Deaths.” This anecdote is surely a relief to anyone who knows the maddening silence of early creativity, but London provides some useful advice useful to any writer employ:

"...Don’t write too much. Concentrate your sweat on one story, rather than dissipate it over a dozen. Don’t loaf and invite inspiration; light out after it with a club, and if you don’t get it you will nonetheless get something that looks remarkably like it..."

In a world in which no one knows where literary attention will go, which trends the papers and publishers will follow, writers are wise to pay attention to London, who above all knew that writing demands hard work. Keep at it, he would say, and make sure to keep a notebook.

*Click here for London's editorial.