The British have had ripe occasion recently to appreciate a leader whose oratory and philosophy were integral to his ability to improve the world. With movies like Dunkirk and Darkest Hour and TV shows like The Crown, memories of Winston Churchill, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, sting all the more sharply as they are juxtaposed against what many view as the failures of some of our current leaders to live up to truly noble aspirations. It's always good to remember our presidents and statesmen who led with a certain moral obligation, integrity of character, humanistic concern, and displayed a talent for language.

This President's Day, let us enjoy our time off (if you’re lucky), and revisit the writings, orations, and philosophy of past presidents who had that precious ability to enrich their characters and inspire others with the merit of their words and deeds.

This President's Day, let us enjoy our time off (if you’re lucky), and revisit the writings, orations, and philosophy of past presidents who had that precious ability to enrich their characters and inspire others with the merit of their words and deeds.

Notes on the State of Virginia by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson barely intended this book to exist, initially writing it to explain his homeland and government to a French colleague. As a frequent writer and thinker, Notes on the State of Virginia contains the prosaic, like a catalogue of crops suitable to the commonwealth’s climate, as well as the illuminating, like Jefferson’s opinions on slavery, civil liberties, and politics.

His perspective on race is hardly to be admired—he argues that blacks are inferior to whites and that the two races could never live together in a free society. More interesting is his argument in favor of the separation of the state from religion, on the grounds that government need only be involved in what harms another, with the pure religious beliefs of a neighbor having no power to harm person nor property. Jefferson also mounts an argument against war as being immensely costly, advocating instead for open trade and civil liberties as qualities of a truly strong nation.

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates

When Abraham Lincoln debated Stephen Douglas for an Illinois Senate seat, one speaker would get to speak for an hour, the opponent and hour and a half, capped by a half hour response from the first speaker. Today, a presidential debate rarely lets a candidate argue their point for longer than two minutes. In 1858, the man who would become our most respected president was given the chance to advocate for his political vision on an intellectual and philosophical forum far more rigorous than what we allow our leaders today.

The writings and speeches of Abraham Lincoln constitute some of the best political thought in U.S. history, and are elevated by the legacy of a man who seems to have balanced both his ambition and sense of duty with an integrity unmatched by any other major leader. Yet reading the speeches (published in a book, they were integral to Lincoln’s election to the presidency) reveals his moral shortcomings, as he professes his belief in the intellectual superiority of whites. Yet crucially, Lincoln argues against slavery and advocates for the recognition of the basic humanity of black Americans. Something startling is the raucous cheers Stephen Douglas achieved from the audience when announcing his full-throated racism and his favoring of slavery. This Presidents' Day, it would help us to remember how and when a respectful, dignified, and humane vision persevered over self-righteous and unashamed troglodytes.

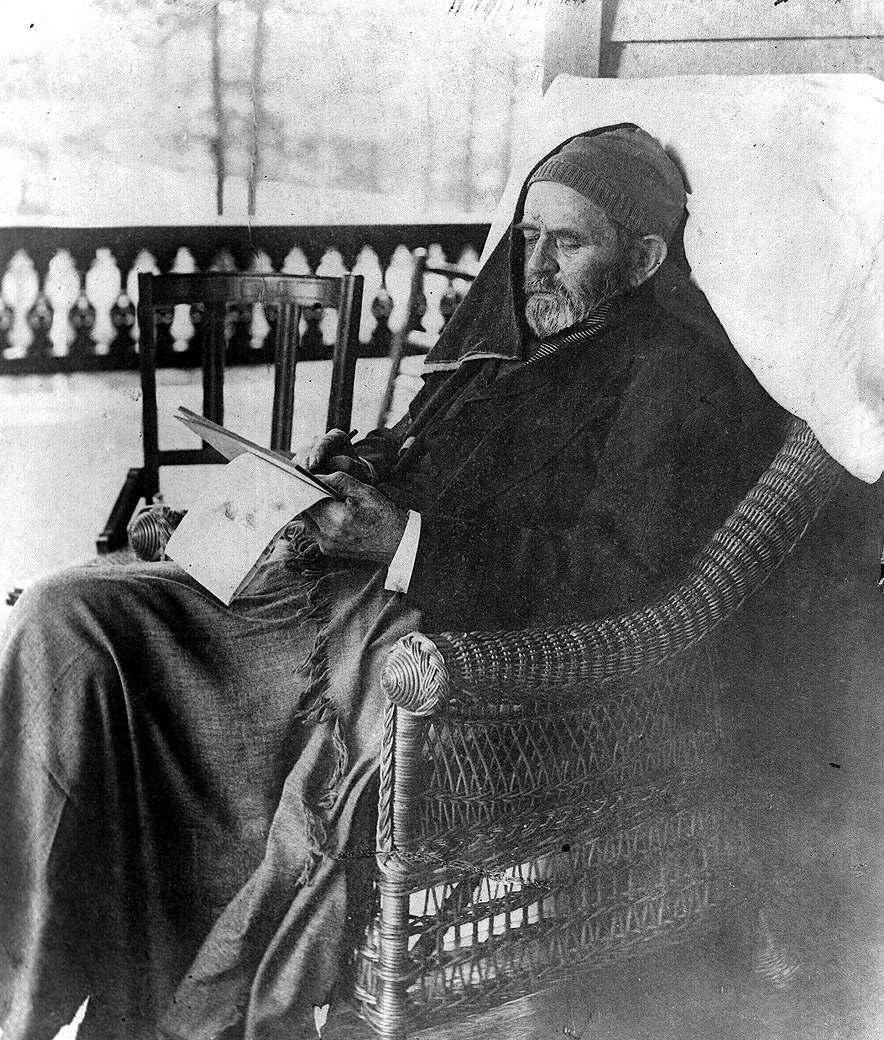

The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

The revival of Ulysses S. Grant, now with a blockbuster biography by Ron Chernow, is in full swing. For many decades, perhaps for over a century, Grant has been blamed for the corrupt occupants of his executive branch and plagued by an exaggeration of his (contained and infrequent) alcoholic benders. But in recent years, historians have propped up the principled president who extinguished the first KKK and avoided appeasing moderate Republicans who wanted a restoration of easy commerce, at the expenses of promises made to uphold equality and liberty to American citizens.

The revival of Ulysses S. Grant, now with a blockbuster biography by Ron Chernow, is in full swing. For many decades, perhaps for over a century, Grant has been blamed for the corrupt occupants of his executive branch and plagued by an exaggeration of his (contained and infrequent) alcoholic benders. But in recent years, historians have propped up the principled president who extinguished the first KKK and avoided appeasing moderate Republicans who wanted a restoration of easy commerce, at the expenses of promises made to uphold equality and liberty to American citizens.

Unlike historians, readers of literature have long found consensus that Grant’s memoirs are the finest writings produced by any American president. Some suggest that it is no accident that the best presidential book concerns not politics but military life, focusing primarily on Grant’s experience in the Mexican-American and Civil wars. Grant writes with a measured, sober, exact prose that led publisher Mark Twain to compare it to Caesar’s Commentaries and remark, “I was able to say in all sincerity, that the same high merits distinguished both books—clarity of statement, directness, simplicity, unpretentiousness, manifest truthfulness, fairness and justice toward friend and foe alike, soldierly candor and frankness, and soldierly avoidance of flowery speech.”

The Essays and Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt

Roosevelt’s 'Man in the Arena' adage endures as a popular bit of wisdom, and for good reason: it has and will always be true. Roosevelt was an avid author, covering topics of historical figures like Cromwell, game hunting out west, fighting in the Spanish-American War, and his journeys abroad in places like Brazil. A book collector can surely spend a lifetime and a fortune assembling a captivating library of the 26th president’s manifold interests and concerns.

Theodore Roosevelt’s pugilistic writings are redolent of a man always in the act of compensating for something (Gore Vidal: “Give a sissy a gun and he will kill everything in sight”). Certainly we will not consider it to be “toughness” when a person travels thousands of miles to slaughter endangered African megafauna with a rifle. But Roosevelt, in his literary stride, preaches both the doctrines of spiritual and physical strength, as well as employing that strength to help others, while believing in the inherent dignity and humanity of women, children, and the poor. "I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life; I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well,” Roosevelt said in a 1910 speech to an audience in Des Moines, Iowa. The Rooseveltian zest for the strenuous life inevitably seduces us, and reminds us that our citizenry faces no threat from the outside more significant than what damage we can inflict on ourselves by way of our own idleness, ignorance, fear, and bigotry.