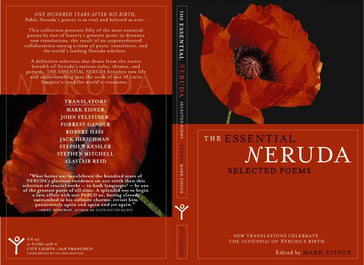

In 2004, Mark Eisner's edited bilingual collection of Pablo Neruda's poems, The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems, was published by City Lights. It has gone on to receive much acclaim, and indeed is the bestselling edition of Neruda's poetry in America. Eisner is currently at work on an important documentary on the late Chilean poet, The Poet's Calling. We had the opportunity to interview him about the process of editing and translating Neruda, as well as the work he has been doing on the documentary film that's currently in production.

Books Tell You Why: How did you become interested in translating Neruda's work? On a related note, could you tell us a bit about the origins of The Essential Neruda? And what have been some of the greatest challenges of translating Neruda and putting together the collection?

Books Tell You Why: How did you become interested in translating Neruda's work? On a related note, could you tell us a bit about the origins of The Essential Neruda? And what have been some of the greatest challenges of translating Neruda and putting together the collection?

Mark: After backpacking through three years of dreams and adventures down through Latin America, I found myself in Chile, that slender country sliding off towards Antarctica, working on a rustic ranch in the rugged central valley. It was Pablo Neruda’s earth. Here grew his red poppies that flower his verse; here grew the grapes that made his velvet red wine; close nearby was his sea, the source of so many metaphors.

As a junior at the University of Michigan, I had studied and worked abroad in Central America. A friend told me to take along some Pablo Neruda, and I have ever since; that same weathered book was always in the top of my tattered green pack from Cuba to Mexico to the silver stones of Macchu Picchu. But in Chile, Neruda was everywhere. I became saturated by his poetry at the same time that my Spanish, after all these years, really had reached a point that I could penetrate his original verse in his own language.

Foreign languages, despite how much I’ve been involved with Spanish, in particular, have never come quickly to me, but after all that time on the road, interacting almost completely in Spanish, sometimes stopping to take classes, and attempting to read in original Spanish, I finally felt I had touched his core, and the experience was intense. Obviously, I knew much was always going to be lost in translation, but not only had I felt I achieved a new level of intimacy with his poetry, with him himself by being able to zone in on the original words, raw and naked, but while before I could hear the sounds and have a basic understanding of the words, now I was being able to pick up on the nuances that I had missed.

There were many beautiful existing translations, and it was through the overall quality of the translations in the edition I had that I had received so much pleasure through the years. However now that my Spanish ability had reached the point that I could translate the words myself, I realized that many poems did not flow as I felt they should and I often had interpretive differences with them. As I talked to some others, there seemed to be a consensus that for a poetry of Neruda’s stature, while there had been some truly outstanding translations already, especially by Alastair Reid, all of which had made him so popular in the English-speaking world, he was still underserved by the quality of many of them.

A translation is complicated with so many different possibilities. One poet, one reader, can sense a poem differently than another does. There can be no “definitive” translation. As Gregory Rabassa, a well-known translator of Latin American literature from Mario Vargas Llosa to Gabriel García Marquez puts it: "a translation is never finished...it is open and could go on to infinity."

There is also the argument put forth by John Felstiner, who has written a very important book about translating based on his experience with just one single piece of Neruda’s canon, The Heights of Macchu Picchu. In it it he indicates the breadth of analysis and interpretation that must accompany the art of crafting a new translation. “With hindsight, of course,” John wrote, “one can all too easily fault earlier practitioners or forget that one’s improvements depend on their work in the first place. And possibly the early stages of translating a poet is marked with too much fealty: word or sense-for-sense renderings that stop short of exploiting the translator’s own tongue. Still, the essential question is not one of stages, of early as against contemporary versions. We have always to ask if a given translation comes across in its own right, as convincing as any good poem of the day. In most cases, the idiom of translators goes stale sooner than that of other writers, so that ideally, the salient poets from any period deserve retranslating for the ear of each new generation.” John later became a contributor to The Essential; I also worked with him some when I did graduate work at Stanford, where he’s a Professor in the English Department.

Then, somewhat magically just in general but also in terms of the timing, I met a young Chilean woman at La Chascona, Neruda's eccentric house in Santiago, which I’d often visit when I took a break from the ranch to spend some time in the city, just a couple hours away. She was working for the Pablo Neruda Foundation while doing graduate work in feminist Latin American literature at the poet’s old school, the University of Chile. She let me sit at Pablo’s desk, with his framed picture of Walt Whitman on it. She introduced me to her professors and members of the Foundation, and it was in these conversations there that the idea for this book was conceived: in honor of the centennial of Neruda’s birth in the year 2004, a new book of translations would be born as a fresh voice, involving an unprecedented collaboration with academics to better empower the translator-poets.

Then, somewhat magically just in general but also in terms of the timing, I met a young Chilean woman at La Chascona, Neruda's eccentric house in Santiago, which I’d often visit when I took a break from the ranch to spend some time in the city, just a couple hours away. She was working for the Pablo Neruda Foundation while doing graduate work in feminist Latin American literature at the poet’s old school, the University of Chile. She let me sit at Pablo’s desk, with his framed picture of Walt Whitman on it. She introduced me to her professors and members of the Foundation, and it was in these conversations there that the idea for this book was conceived: in honor of the centennial of Neruda’s birth in the year 2004, a new book of translations would be born as a fresh voice, involving an unprecedented collaboration with academics to better empower the translator-poets.

Edmund Keeley, prominent translator of Greek poetry, wrote: "translation is a moveable feast...there must always be room for retouching and sharpening that image as new taste and new perception may indicate." In the case of this project, the discovery of those new perceptions was achieved through a collaborative effort. Scholars — Nerudianos — were asked to participate, forming a bridge linking academics, editor, translators and poets.

One introduction led to another, around the world, and before I knew it I somehow, rather unbelievably had some of the top Neruda experts from the University of Chile to the University of California-San Diego engaged as well as poet/translators ranging from U.S. Poet Laureate emeritus Robert Hass to Neruda’s favorite translator, the late Alastair Reid.

Books Tell You Why: How long did the book take to complete?

Mark: I came back to the States with the seeds of the project in 1999, still not sure if it was something I wanted to pursue, or how best to go about achieving it. I then received a fellowship to get my Masters in Latin American Studies at Stanford, where I was drawn to study political science and economy as much — if not even more — than literature at the time. So while I worked on furthering my knowledge of Neruda and other Latin American literature, not all of my energy was focused there. And with everything going on, the translation project advanced slowly, with baby steps, on the side, as I tried to absorb it all in.

After graduating, though, the Latin America Studies Center named me a research fellow, and the following year, a visiting scholar, so that I could pursue my academic/creative Nerudian projects, which by 2003 included the documentary as well. It was during these two years leading up to the centennial that the project really came together. It’s very hard to quantify how much time it actually took, especially considering that so much of this was a collaborative process, and so there was also a lot of wait time for questions, translations, discussions, to be answered, crafted, and flow all around.

Books Tell You Why: What was one of the most exciting aspects of putting the collection together?

Mark: Besides the incredible thrill of the actual publication, and the great reception it received, three aspects were particular exciting. First, simply the surprise of discovery that occurred through the art of translation, breaking through and all of a sudden being able to render something so allusive and complicated into English that keeps both the inherent poetic beauty and literal meaning of the original — that essential balance and truth — discovering those buried jewels that arise to the surface from deep within the original text.

Mark: Besides the incredible thrill of the actual publication, and the great reception it received, three aspects were particular exciting. First, simply the surprise of discovery that occurred through the art of translation, breaking through and all of a sudden being able to render something so allusive and complicated into English that keeps both the inherent poetic beauty and literal meaning of the original — that essential balance and truth — discovering those buried jewels that arise to the surface from deep within the original text.

Second was the opportunity to collaborate with such a group of creative, brilliant minds, and such wonderful souls. I mean, when a poet you’ve revered since college, whom as you’ve started to work with him personally you’ve realized beyond the words he’s also such a kindred saint of a man, with a true genius mind — and you’re twenty-nine years old and down in Chile working with young poets and you get an email from him saying, “I was reading [Poem 15 of the Twenty Love Poems] out loud to myself and it struck me that the alexandrines sounded exactly like an old Leonard Cohen lyric — ‘Suzanne’ — so I tried to render that rhythm.” Well…

Then there was the wonder of being published by City Lights, the San Francisco-based bookstore and publisher founded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1953. The Beats used to be my literary idols (although over time “heroes” became the most appropriate word). Indeed, both my writing and, to a degree, life course after college was heavily influenced by them. Being published by City Lights, having the relationship I have with them now, doubled the dream that this book has been. Now that I’m not living there anymore, to drink wine with Lawrence on most of my visits back never ceases to be an amazing event.

Do you translate other poets and/or poetry in other languages? What other translation work have you been involved in?

Unfortunately the only foreign language I’m fluent in is Spanish, so I haven’t worked with anything else.

I had the most beautiful experience of translating my good friend Tina Escaja’s book length poem, “Caída Libre / Free Fall.” A native of Spain, she’s currently a Professor at the University of Vermont, specializing in Latin American poetry and gender studies, among a million other thing. A great amiga for a decade, and such a supporter and helper for my work. Besides the beauty of the process, there was also such satisfaction enabling English speakers to access her award-winning book. It was published by Fomite Press earlier this year. When I mention the collaborative part, it’s that after working on Neruda for so long, who died the year I was born, to whom I couldn’t just call or drop an email and ask exactly what he meant with one phrase or another or “how do you think this sounds?” it was so refreshing and thrilling to interact with her on the word-decision marking process on her own words.

Tina and I have also co-edited a multilingual anthology of Latin American “Poetry of Resistance.” We feel what’s so unique and important about it is that the poems express a range of perspectives rarely contained in just one collection, including feminist, queer, indigenous, urban and ecological themes, along with the more historically prominent protests against imperialism, dictatorships, and economic inequality. Every Latin American country is represented, and multiple languages such as French, Quechua, Maya, Mestizo, and Mapudungun are included and translated, the original en face with the translation.

Prominent poets such as the newly named U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera along with emerging translators have crafted brilliant fresh versions of poems, many of which have never published in English before, especially in book form. I translated three and co-translated two others. We’re currently looking for a publisher.

There’s been some other small literary translation work here and there, but in the course of working on my almost-finished biography of Neruda, I’ve not only translated parts of many poems not in the Essential but also a great deal of his prose and secondary sources, including interviews. The project has such a whole other dynamic with all the Spanish involved.

Books Tell You Why: Could you talk a bit about the Neruda documentary you're creating and what you hope to accomplish with the film?

Mark: The documentary is actually a new version of a cinematic exploration of Neruda we rushed to have ready to premier on Neruda’s centennial, July 12, 2004. It was shown in Neruda festivals, some regular film festivals, and college campuses, and it won the 2004 Latin American Studies Association’s Award of Merit in Film. Isabel Allende narrated it, which was a tremendous experience in its own right. I can recall talking about the magical realism stories of her granddaughter as we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge in my beat-up old Subaru from her home in Sausalito, where we worked together on the script to the recording studio in San Francisco.

There was a general consensus afterwards, though, that while the project had lots of heart and soul, it was flawed from a filmmaking perspective and thus never had the legs we wanted. We never even got enough money to pay for all the archival material.

Five years later, I had gotten a new team around me and applied for and received a production grant from Latino Public Broadcasting, not only giving us some seed money but giving up a path towards a PBS broadcast, always my highest goal for the project. Due to funding issues and time needed on other projects, we’re just now in the final stretches. This version has no narrator, instead we realized the uniqueness of our project are the fascinating, endearing interviews we recorded with some of his closest surviving friends, from prominent painters to political allies to the carpenter who built his mythical Isla Negra home on the coast. We let them tell Neruda’s story.

We also have magical interviews from Chileans of all stripes. We met a construction worker at a site where they were expanding Santiago’s metro. When asked what Neruda meant to him, he replied, animated, “Pablo Neruda is one of the greatest poets we have here in Chile. And there are many generations of Chileans who feel he speaks for them through his poetry. Whether it’s the romantic Chileans or the combative Chileans like him. He’s part of our national legacy. Neruda represents all of us, not just the worker. He represents the student, the housewife, or an executive who’s drawn to poetry.”

Through all of them, the film vividly depicts his monumental life, potent verse, and ardent faith in the “poet’s obligation” to use poetry for the social good. In doing such, it will paint a unique, intimate portrait of Neruda: the person, the poet, the activist, like no other work has before. For not only will it be the first broadcast quality, feature-length documentary on Neruda in English, no documentary in any language has portrayed all of these three aspects as dynamically or completely as we do. We are entering the post-production stage. More information, as well as how you can help and get a personalized copy of The Essential Neruda and more by doing so, can be found at www.nerudadoc.com.

Neruda once wrote, “Poetry is like bread; it should be shared by all, by scholars and by peasants, by all our vast, incredible, extraordinary family of humanity.” This sentiment highlights our motivation for making this film. We expect it to appeal to the vast amount of readers who already appreciate Neruda, providing them with further depth of understanding and enjoyment. At the same time, we believe it will attract a new, expanded audience. We want all viewers to see, and feel, how poetry can illuminate them intellectually, spiritually, and socially.

Books Tell You Why: For readers just being introduced to Neruda, what works are must-reads?

Mark: So many of them are “must-reads.” In the Essential, we tried to provide golden nuggets from each of his major chapters, but he’s so prolific, with so many amazing poems (along with a lot of not-so-amazing). The thing about Neruda is that his poetry was constantly evolving throughout the course of his life, from one style to another, from one focal point to another. That’s why we tried to cast a wide net. Somehow I think we pulled that off. Many reviews reflected this. The Austin Chronicle said that, in our 200 bilingual pages, “it somehow manages to convey the fullness of Neruda's poetic arc: Reading it is like reading the autobiography of a poetic sensibility (granted, the abridged version)." But to say just look at its table of contents isn’t the proper answer to your question.

Mark: So many of them are “must-reads.” In the Essential, we tried to provide golden nuggets from each of his major chapters, but he’s so prolific, with so many amazing poems (along with a lot of not-so-amazing). The thing about Neruda is that his poetry was constantly evolving throughout the course of his life, from one style to another, from one focal point to another. That’s why we tried to cast a wide net. Somehow I think we pulled that off. Many reviews reflected this. The Austin Chronicle said that, in our 200 bilingual pages, “it somehow manages to convey the fullness of Neruda's poetic arc: Reading it is like reading the autobiography of a poetic sensibility (granted, the abridged version)." But to say just look at its table of contents isn’t the proper answer to your question.

What struck me most while doing the interviews for the movie was how time and time again people called out Canto General his epic interpretation of this history of the Americas, a bible like book of the history of the Americas, as their favorite, as their most important book. Jose Corriel, the Santiago metro construction worker we interviewed for the film told me that, despite having Twenty Love Poems, Residence on Earth, and his memoirs at home, Canto General is his favorite book. Corriel explained, “It shows us the Americas’ history from a different point of view...We could call it the history told by the conquered.”

Yet it’s hard to skip the classic Twenty Love Poems. Poems I, XV, and XX stand out. Then there’s the profound poetry of Residence on Earth, which goes from the surrealism of a depressed mind to a total shift to straightforward political poetry after he witnessed first-hand the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. Many say it’s the most important book of Latin American poetry.

The odes, as well, are both beautiful and essential, where he shows the social utility in everyday objects as he exalts them with incredible lyrical prowess. And there are jewels throughout, from his autobiographical book Isla Negra he wrote for his sixtieth birthday so some of his other love poetry in The Captain’s Verses and One Hundred Love Sonnets. In the dozen or so other books he wrote later in life, each one has a treasure waiting for you.

Books Tell You Why: What are some of your favorite Neruda poems, both in the original Spanish and in translation?

Mark: It’s hard to list favorites, especially since Neruda’s work is so vast, and with so many different dimensions and styles, as my answer to the previous question alludes to. My “favorites” are constantly changing due to what’s going on in my life, or if something political is charging me, kind of like with music and you’ll have one song you keep listening to over and over one week and another the next. Neruda’s amplitude and variation allows for this. I’ve just had one of his Heights of Macchu Picchu poems in my head in fact because a track of Joan Baez singing it in such a stirring fashion that I get goose bumps came up rather randomly in my iTunes the other day (it’s the opening to her version of “No Nos Moveran (We Shall Not Be Moved.)”. “Heights of Macchu Picchu” is always one of my favorite poems. So much of Canto General, the greater book, his interpretation of the history of the Americas, is unprecedented and still so moving as well.

And now after I just wrote about what Bob Hass said about his translation, I’m sure “Poem XV,” and in particular, what he did (as you asked, in English or Spanish) will be on my mind.

In truth, the love poems don’t do it for me as much anymore, although they’re always there, many of them simply classics you can always find emotion in.

Neruda’s beauty is that there is always something there for whatever mood you’re in---during the Iraq War his poem “I Explain Some Things” about the Spanish Civil war took on a new resonance for so many. Need some soul searching? “Comes a Time I’m Tired of Being a Man” — from the poem “Walking Around.” Affirmation on the beauty of life? “October Fullness.”

Books Tell You Why: Do you have any advice for poets or poetry readers who would like to get involved in literary translation work?

Mark: Two things have kept me passionate about the art of translation. First, the ability to allow readers to access amazing poetry that you truly believe should be read, that currently can’t be by due to language barriers. You can provide the portal. In doing so, it is crucial that both the inherent poetic beauty of the original is translated in conjunction with the literal meaning. This, to me, creates such a challenging creative process that fuels me, that can be so exhilarating when you get it right. See what Bob Hass did with Poem XV for example, as an example of how to stretch it to make it work, to reassess what the term “faithful to the original” can really mean.

I would also stress seeking the input of others. That was the whole idea behind the Essential Neruda, that it wouldn’t be one translator working alone in an ivory tower. The creative process involved in doing so is so challenging it can be exhilarating. I’m not sure if this will make sense, but as I previously quoted Gregory Rabassa, “a translation is never finished...it is open and could go on to infinity.” So let others become part of the process, making your work as dynamic and rich as possible. When the original poem is set, the translation can be, should be open to many inputs.

Finally, one thought I always try to keep in mind while finishing a piece, comes from the kindred spirit Alastair Reid, Neruda’s favorite translator who meant so much to me as a friend and a mentor. He passed away last year. Translation, Alastair wrote, is “a process of moving closer and closer to the original, yet of never arriving. It is for the reader to cross the page.”

Many thanks to Mark Eisner for taking the time to share his experiences and insights with us. You may respond to Mark directly with your reactions in the comments section below.