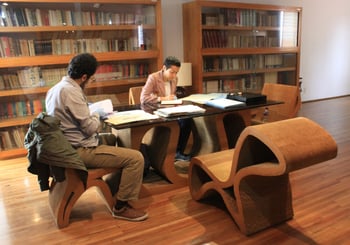

In May, we had the opportunity to visit the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros, the former studio of the famous Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, located in Mexico City. In addition its continuing function as a gallery space, the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros also contains the archives and personal library of the painter. We were thrilled to get a chance to visit the muralist’s preserved library and to examine some of the books contained within it. We also had the opportunity to speak with Mónica Montes, one of the primary archivists at the space. She agreed to an interview with us about Siqueiros’s library, and we are excited to share her knowledge, thoughts, and insights.

*Interview conducted in Spanish and translated into English by the interviewer, Audrey Golden

Books Tell You Why: When did the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros open to the public?

Books Tell You Why: When did the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros open to the public?

Mónica Montes: On January 29, 1969 the painter and muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros decided to open what was then his home and studio in Mexico City as the Sala de Arte Público (Public Art Gallery). He mounted an exhibition with a selection of studies, sketches, models, sculptures, and photographic enlargements of work that, at that time, were related to the mural “The March of Humanity” that he and his staff were creating.

Books Tell You Why: Did the space already contain Siqueiros's personal library at that time?

Mónica Montes: The library was donated on December 12, 1973, by public testament, to the people of Mexico by David Alfaro Siqueiros, along with his personal archive. The latter contained an important selection of easel and mural works, as well as the installations housed at No. 29 Tres Picos in Mexico City, and objects from his mural studio in Cuernavaca, Morelos, called La Tallera.

Books Tell You Why: Is the library open to researchers?

Mónica Montes: The personal Library and Archives of David Alfaro Siqueiros are open to the general public by appointment.

Books Tell You Why: Who are some typical researchers in the collection? Do they come primarily from Mexico? Or from other parts of the world, too?

Mónica Montes: Researchers that visit the library are mostly domestic and foreign students with bachelor's or master’s degrees interested in the life and work of the artist. Our foreign visitors primarily come from Argentina, Chile, and the United States.

Books Tell You Why: What are some of the most interesting books in the collection?

Books Tell You Why: What are some of the most interesting books in the collection?

Mónica Montes: The richness of the collection of the Siqueiros library lies in part in the fact that a significant number of the publications were the artist’s study materials, while others were presented to Siqueiros by important personalities from the arts and letters, as well as from family and friends. In addition, there is a linguistic richness of the collection, given that it contains books in Russian, Japanese, Greek, Chinese, English, Italian and German.

Outstanding objects in the collection include, to mention just a few:

Carlo Quattrucci. España 1936-19.. Omaggio to Rafael Alberti, Federico García Lorca, Antonio Machado (1970). This publication features a dedication to Siqueiros by the poet Rafael Alberti and the artist Carlo Quattrucci.

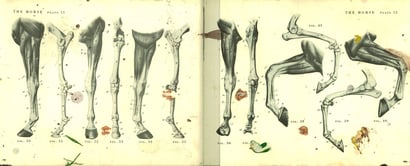

An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists (New York: Dover Publications, 1949). This publication was material that David Alfaro Siqueiros studied during the process of making his mural work Apotheosis of Cuauhtemoc, completed in 1950 and displayed at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists (New York: Dover Publications, 1949). This publication was material that David Alfaro Siqueiros studied during the process of making his mural work Apotheosis of Cuauhtemoc, completed in 1950 and displayed at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

Pablo Picasso, Paul Eluard, Le visage de la paix (Paris: Editions Cercle D'Art, 1951). This text has a dedication to Siqueiros and his wife, Angelica, from the French poet Paul Eluard.

Books Tell You Why: When I was in Mexico City, you showed me a book that Neruda had inscribed to Siqueiros. Could you say a bit more about it?

Mónica Montes: Correspondence between and publications of Siqueiros and Pablo Neruda housed in the collection are proof of the close friendship between these two great personalities of art and culture. The publication that I showed you during your visit is entitled: Presence of Ramon Lopez Velarde in Chile. This is a bibliographic gem that is not widely known. The book includes an essay entitled “RLV,” in which Pablo Neruda explores the work of the poet Ramon Lopez Velarde from the Mexican state of Zacatecas, presenting readers with a timely selection of the prose and poetry of this great Mexican writer. It is very likely that this text was given to Siqueiros when he was imprisoned in the Penitenciaría de Lecumberri after he was accused of the crimes of “social dissolution, individual resistance, and insulting the authorities.”

Books Tell You Why: Did Siqueiros keep his library organized in a specific way? If so, has the Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros maintained that organization system?

Mónica Montes: Siqueiros organized his more than 2,000 books through three concepts: art, politics, and “various.” Acting on his interests and intentions, the Siqueiros library has, to date, maintained the original organization.

Books Tell You Why: How did you begin working at the Sala de Arte Público?

Mónica Montes: I started while fulfilling my Social Service requirement and assisting in the area of research, after which after I was hired to coordinate the “Siqueiros Archive.” From then up until now, my work has as its main axes both conservation and dissemination of the contents of the Archive (including materials within the library). An important part of my work involves advising researchers, students, artists and anyone interested in the legacy of this iconic figure of Mexican modernity.

Books Tell You Why: What have some of your most interesting experiences been at the Sala de Arte Público?

Mónica Montes: They are many and varied, but certainly any and all experiences involving our research into and repositioning of dialogue among the contemporary languages of art and historical heritage, which are central to our museum. It has truly been an enriching experience to explore the contents of the Archive and Library from other perspectives. The exhibition Réquiem (2013) is just one example in which we used the materials contained here to showcase alternate viewpoints. As part of the exhibit, the Mexican artist Emilio Chapela recreated an exact wooden copy of each book in the muralist’s collection. We might interpret Réquiem in many ways: as a funeral march that alludes to the present-future of a personal collection of texts, as a reinterpretation of the digitalization process, and as the conceptualization of the original library that contains the book as an object.

Many thanks to Mónica for taking the time to participate in this interview with us. We are thrilled to share more information about the Sala de Arte Público with American readers who are interested in Latin American art, literature, and politics, and we encourage you to plan a trip to Mexico City to explore the gallery and archives for yourself. We're quite certain that, once you go, you'll want to return as soon and as often as possible.