One of the best known authors of the twentieth century, Isaac Bashevis Singer won literary accolades all over the world, including that most illustrious of awards, the Nobel Prize in Literature. The 1978 Nobel laureate wrote primarily in Yiddish, yet the majority of his published works are in English--a fact that makes Singer all the more fascinating to both scholars and collectors.

Following in a Brother's Footsteps

Born in a village outside Warsaw around November 21, 1902, Singer would not be the first writer in his family. His older brother, Israel Joshua Singer, established himself as an eminent author. He was part of the short-lived expressionist movement in Yiddish literature IJ, as Israel was known, attracted the notice of editors at the New York journal Jewish Daily Forward and became a correspondent for the newspaper, all the while publishing short stories and travelogues.

Singer was determined to follow in his brother's footsteps--and to make his own name. In 1923, he went to Warsaw and obtained a position as a proofreader at the journal Literarishe bleter. He would stay with the journal for a full decade. On the side he also translated modern European novels from German to Yiddish. Singer began to publish his own work in Literarishe bleter. But in order to distinguish himself from his brother, he adopted the pseudonym Yitshok Bashevis. The surname was derived from his mother's name. Subsequent work would be published under this and other pen names.

Singer was determined to follow in his brother's footsteps--and to make his own name. In 1923, he went to Warsaw and obtained a position as a proofreader at the journal Literarishe bleter. He would stay with the journal for a full decade. On the side he also translated modern European novels from German to Yiddish. Singer began to publish his own work in Literarishe bleter. But in order to distinguish himself from his brother, he adopted the pseudonym Yitshok Bashevis. The surname was derived from his mother's name. Subsequent work would be published under this and other pen names.

In 1932, Singer founded the magazine Globus with Arn Zeitlin. It appeared monthly for three years. Singer's novel Satan in Goray first appeared on the pages of Globus in January 1933. Two years later, the Yiddish PEN club published the story in book form. The club called the book the "most promising first novel from a local writer."

A Tireless Self-Starter

When Singer emigrated to the United States in 1935, his brother helped him get a position at the Forward. Again, Singer published under a number of different pseudonyms,  such as Y Wanshavsky and D Segal. (Singer used the latter exclusively for an advice column where he answered letters from readers.) Even after he'd firmly ensconced himself as a preeminent author, Singer still sometimes used pen names in the Forward.

such as Y Wanshavsky and D Segal. (Singer used the latter exclusively for an advice column where he answered letters from readers.) Even after he'd firmly ensconced himself as a preeminent author, Singer still sometimes used pen names in the Forward.

Though Singer was hardly the only US-based author writing in Yiddish, he was the only one who managed to build significant name recognition. His talent for writing was equaled only by his ability to promote himself. Singer worked tirelessly with translators to ensure that the English versions were as accurate--and true to his art--as possible. To gain empathy from his American audience, Singer called English his "second original language." He also worked hard to find an American publisher, working first with Noonday Press to publish Satan in Goray.

In 1960, Noonday Press merged with Farrar Strauss & Giroux, which would be Singer's primary American publisher for the rest of his career. Thanks to his efforts, Singer found his way into prominent American periodicals like The New Yorker, Esquire, and even Playboy.

Controversial in His Own Community

However, Singer was not without his detractors. One of the most vocal was the widow of fellow Yiddish writer Chaim Grade. Inna Grade vociferously argued that her husband should have won the 1978 Nobel Prize for Literature instead of Singer. She even refused to say Singer's name and said, "I am very sorry that American is celebrating the blasphemous buffoon." Orthodox critics took issue with Singer's portrayals of sexuality and his incorporation of the devil as a character.

Detractors also didn't appreciate the fact that Singer focused more and more on his English-language work. Ever the champion of Yiddish, Singer always published first in Yiddish, usually in the Forward. But he increasingly seemed to view these versions as published rough drafts. He worked closely with translators to ensure the integrity of the translations...but he also often changed the story or even altered the endings completely in the English versions. Singer came to think of these English editions as the "second originals," an interesting concept in the world of rare book collecting, where so much value is attached to firsts.

Detractors also didn't appreciate the fact that Singer focused more and more on his English-language work. Ever the champion of Yiddish, Singer always published first in Yiddish, usually in the Forward. But he increasingly seemed to view these versions as published rough drafts. He worked closely with translators to ensure the integrity of the translations...but he also often changed the story or even altered the endings completely in the English versions. Singer came to think of these English editions as the "second originals," an interesting concept in the world of rare book collecting, where so much value is attached to firsts.

Collecting Isaac Bashevis Singer

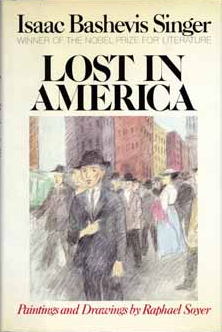

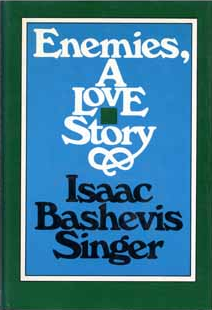

You'll find a cursory bibliography of Singer's works at the official website of the Nobel Prize. But serious collectors will need to dive much deeper. Singer was an incredibly prolific author, publishing in English thirteen novels; ten volumes of short stories; five volumes of memoirs; fourteen children's books; and three anthologies of selected writings. In Yiddish Singer published only five novels in book form, along with an incredible wealth of ephemera in various periodicals. His stories first appeared in the Forward, and then in Yiddish papers around the world.

Any robust Bashevis collection will necessarily include quite a number of newspaper clippings and other delicate items. Because they're generally printed on cheaper paper, these items require careful preservation and storage. Separate periodical pages from each other with archival tissue paper, and avoid affixing clippings with conventional adhesives.

Any robust Bashevis collection will necessarily include quite a number of newspaper clippings and other delicate items. Because they're generally printed on cheaper paper, these items require careful preservation and storage. Separate periodical pages from each other with archival tissue paper, and avoid affixing clippings with conventional adhesives.

And although a traditional collection of modern firsts might include only the first edition of each work, the same approach won't work for collecting Isaac Bashevis Singer. Your collection will likely include multiple versions of some works perhaps the serialized version from the Forward and the English novel version, or maybe both the Yiddish and English versions.

And some reissues of Singer's works are also significant, such as the 1943 edition of Satan in Goray, published the year Singer gained US citizenship. Furthermore, both the Franklin Library and the Library of America have offered editions of Singer's works; Singer was the first writer the Library of America ever published in translation.