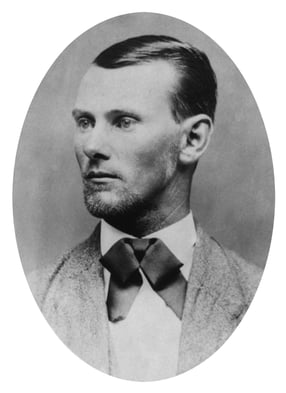

This blog post is not the first place it’s been pointed out that the Wild West era lasted a scant few decades—compared to the century-plus of folk songs, dime novels, movies, TV shows, and other forms of myth-making that take up (and sometimes interrogate) the inherent romance and drama of the era. Given all that, it shouldn’t really surprise us that Wikipedia’s article on “Cultural depictions of Jesse James” is almost as long as the article on James himself. And yet, the piece leaves out what is arguably the first piece of popular culture that took up the life (and death) of the one of the West’s most notorious outlaws: the touring stage show put on by Robert Ford, James’ assassin, dramatizing the moment when Ford himself put a bullet in the back of James’ head.

Ron Hansen depicts the ostensible assassination, and the subsequent dramatization of that assassination by the very same man who performed the deed, in his novel The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983). The book was ultimately adapted into a movie, well over a century after James’ death, by which time the myth of the James Gang had been almost continuously reflected, refracted, and distorted in the public consciousness—creating, as with so many Western folk heroes, a line between fact and fiction that is not just blurry but virtually immaterial. Not only was the James myth interpreted by his own assassin just after his death, it was conscientiously crafted during his lifetime by John Newman Edwards, a friend of James and fellow anti-Reconstruction advocate.

When the Legend Becomes Fact

Edwards published numerous articles in the Kansas City Times, a newspaper that he founded, where he held up James as an example of the kind of pro-Confederate, anti-centralization folk hero that the West could latch onto. (All of this is after Edwards, aghast at the Confederacy’s defeat, fled to Mexico to pledge himself to Maximilian I.) His op-eds showed great admiration for James and his defiantly anti-Republican attitude, and he seems to have nearly created the myth of James as frontier-Robin Hood out of whole cloth. Though by all accounts none of the proceeds of the James Gang’s numerous train and bank robberies went to the poor, he was somehow spun into a figure of righteous benevolence. James himself even contributed a few pieces to the paper, portraying himself as an innocent victim and fighter for freedom and justice.

In John Ford’s seminal western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Jimmy Stewart admits to his would-be biographer that, despite his reputation, he didn’t actually kill the film’s eponymous outlaw. His interlocutor, a newspaperman, proceeds to tear up the notes he’s taken during the interview, famously insisting: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend!” But in Jesse James’ case no one waited for the legend to become fact. Fact and legend existed side by side in dubious competition from the instant he shot Captain John Sheets during the robbery of Gallatin, Missouri’s Daviess County Savings Association.

The Confederate Robin Hood

The Daviess County Savings robbery—in which James killed a cashier in a case of mistaken identity (he thought Captain Sheets was Samuel P. Cox, who had killed one of James’ fellow guerrillas during the Civil War)—was hardly the first such instance in James’ life. Having grown up in a small, slave-owning family in Missouri, James was embroiled in the conflict from the age of 16. While much of the fighting across the country took the place of skirmishes between uniformed Union and Confederate soldiers, things in Missouri were messier. Much of the strife was taken up with brutal violence between pro-Confederacy guerrilla groups, (known as bushwhackers) like Quantrill’s Irregulars, and pro-Union militias. James followed in his brother’s footsteps by joining up with the former, taking part in the Centralia Massacre, in which a trainload of unarmed Union soldiers were largely scalped and dismembered by the band of outlaws. Shortly thereafter, he took part in the killing of more than 100 Union soldiers who were in the act of surrendering.

Following the formal conclusion of the Civil War, the situation in Missouri failed to stabilize. James continued to be a major player in what began as anti-Union violence, and which (arguably) devolved into less ideological violence—to wit, a long series of bank and train robberies. Sure, they were still against Reconstruction, and would gladly have mounted forces for another secession, but James and his comrades’ primary focus was elsewhere. With Archie Clement, James robbed the Clay County Savings Association in broad daylight. Later, as the head of the James–Younger Gang, he robbed a train in Iowa clad in a KKK mask.

“Oh I Wonder Where My Poor Old Jesse’s Gone”

In September of 1876, The James Gang attempted to rob the First National Bank in Northfield, Minnesota. The robbery was badly botched, and at the end of the ordeal only Jesse and Frank James were left alive. By this time, the legend of the James brothers had grown, and attempts on their lives were frequent and supported by government and law enforcement. Following a quiet period, James would enlist the support of the Ford brothers in a new gang. Soon after, Robert Ford and the Governor of Missouri would (arguably) conspire in James’ death. Ford famously killed James in his own home, shooting him in the back of the head after he put down his pistol and turned around to hang a picture on the wall. Within a short span, the Ford brothers were charged with murder, convicted, sentenced to death, and granted a full pardon.

As any reader of Ron Hansen’s book knows, Bob Ford quickly became reviled across the frontier—in due proportion to James’ status as folk hero. A pair of verses from the widely recorded folk song “Jesse James” should suffice to give a sense of the public feeling around James’ death:

Jesse was a man, a friend to the poor,

He'd never see a man suffer pain,

And with his brother Frank he robbed the Chicago bank,

And stopped the Glendale train…

Now the people held their breath when they heard of Jesse's death,

And wondered how he ever came to fall

Robert Ford, it was a fact, he shot Jesse in the back

While Jesse hung a picture on the wall

Surely this can’t be our Jesse James they’re singing about? Sure, he tended not to actually stick up any passengers during his train robberies, but he was a killer and secessionist.

But when the legend becomes fact, print the legend: for one reason or another, the legendary Jesse James, the tragic hero betrayed by his own men, has taken on a life of his own, existing on a plane above the historical James. His name remains a metonym for all manner of romantic lawlessness, long after public recollection of his (many) specific crimes has largely tapered off.