One evening, John Patrick revved his chainsaw on the president of a power company’s lawn. The playwright wanted to run an extra power line to his new farm in New York state. Having received nothing but a string of empty promises, Patrick decided to take matters into his own hands. So he threatened to cut down the executive’s elm tree unless his concerns were properly addressed. The playwright knew a little about getting what he wanted—he had a Pulitzer Prize, after all.

John Patrick, whose career spanned some four decades, was a consummate professional. Perhaps he was not unimpeachable in temperament, but he was admirable in his work ethic. Patrick was one of the those ambitious and improbably prolific writers who left no medium in show business untouched. As for his outbursts, however, he had become known for them in the theatre. He envisioned them as a productivity hack. Turning vice to virtue, he confessed his paroxysms as manifestations of an “anger that I have to generate and use as a whip to drive myself.”

John Patrick, whose career spanned some four decades, was a consummate professional. Perhaps he was not unimpeachable in temperament, but he was admirable in his work ethic. Patrick was one of the those ambitious and improbably prolific writers who left no medium in show business untouched. As for his outbursts, however, he had become known for them in the theatre. He envisioned them as a productivity hack. Turning vice to virtue, he confessed his paroxysms as manifestations of an “anger that I have to generate and use as a whip to drive myself.”

Following a somewhat wayward youth, the nineteen year-old Patrick began his career at a radio station. As an announcer and writer, he spent five years in broadcasting, composing some eleven-hundred radio plays during his tenure. It was a remarkable record of productivity, one that he continued for years to come while working for the stage and screen.

John Patrick’s dramatic career actually took off on a flop. Patrick’s first play, Hell Freezes Over, had a short run in New York to minimal acclaim. Hollywood, for one reason or another, took his early failure on Broadway as a sign his talents would translate well to cinema. It wasn’t a bad gamble. Patrick would go on to achieve marked success working in both theatrical and cinematic forms, often intertwining the two.

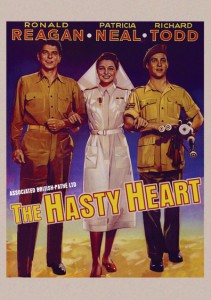

Patrick’s first major triumph came in the late '40s, after his World War II play The Hasty Heart was adapted into a movie starring Ronald Reagan. Written in only twelve days, it was a major plot point in a life that just a few years later would see a Pulitzer Prize (awarded for The Teahouse of the August Moon). Like much of Patrick’s most enduring work, Teahouse is a comedy, and it proved that the playwright could masterfully adapt a novel for the stage. It stands as but one out of many impressive feats from a prolific career. The Internet Movie Database lists fifty-six screen credits to his name, encompassing everything from an episode of Leave it to Beaver to an astonishing eight screenplays in the year 1937 alone.

Yet despite John Patrick’s work ethic, productivity, and volatility, he was no mere careerist—some laborer who saw show business as a place to make a buck and name. In one of his most successful plays, The Curious Savage, the protagonist encounters noble spirits in an unlikely place: within the walls of a mental hospital. In the playbook, Patrick insists, “It is important in The Curious Savage that the gentle inmates of The Cloisters be played with warmth and dignity. Their home is not an asylum nor are these good people lunatics... To depart from this point of view for the sake of easy laughs will rob the play of its meaning." Not only did Patrick have an integral artistic vision for his work, he used his practical ambitions to disseminate challenging themes.

John Patrick died at the age of 90 in a nursing home with a plastic bag over his head. He left a poem to accompany his suicide:

I won't dispute my right to die;

I'll only give the reasons why;

You reach a certain point in time

When life has lost reason and rhyme.

For the playwright who often likened himself to a craftsman or carpenter, the defense is fine enough. Patrick was an artist who relied desperately on his gut and faculties of logic. Without those assets, John Patrick as we knew him would cease to exist. The human may be frail, but the plays and movies, at least, still endure.