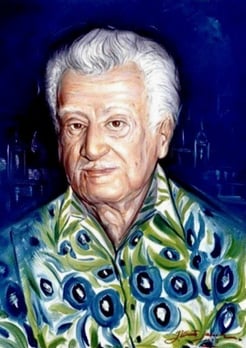

When Jorge Amado died in 2001, people were already talking about him as Brazil’s cultural ambassador to the world. His novels, translated into nearly 50 languages, made many in the West suddenly familiar with the largest Latin American nation. In 1987, Bantam paid $250,000 for the hardcover rights to his novel Showdown. It was a record purchase at the time for a foreign language book, but international readers readily justified the price. Amado’s emphasis on regional dialect, empowered female characters, anti-racism, folk culture, and the dignity of the worker offer a rich and politically-charged vision of Brazilian life. The author himself declared he had done more to introduce the world to Brazil than any institution, any government effort, did.

Comparing himself to the Brazilian government isn’t entirely fair, however. In Amado’s time, the government wasn’t much of a constant or predictable institution. Born in 1912, Amado witnessed the Brazilian Revolution of 1930, marking the end of the Old Republic and initiating a dictatorship. This regime, called the Vargas Era, lasted until 1946, when a leader was once again elected to rule over Brazil.

Comparing himself to the Brazilian government isn’t entirely fair, however. In Amado’s time, the government wasn’t much of a constant or predictable institution. Born in 1912, Amado witnessed the Brazilian Revolution of 1930, marking the end of the Old Republic and initiating a dictatorship. This regime, called the Vargas Era, lasted until 1946, when a leader was once again elected to rule over Brazil.

During the Vargas Era, Jorge Amado was an active political figure and member of the Brazilian Communist Party. He was arrested in 1936, the result of a failed coup, which was backed by the Soviets. In the coming years, the ruling government worked to suppress the Communists. As a prominent communist, thousands of copies of Amado’s books were burned by police in the public square. When the party was finally outlawed, political resentment toward Amado forced him into exile. This antagonism is a far cry from the national sentiment which would heartily embrace him in a few decades.

Living in Uruguay, Paris, Czechoslovakia, and traveling around Europe, Amado realized that politics and writing were both full time jobs, and he would have to pick one to pursue. He chose writing, but politics never left his work. His politics, of course, make Amado a controversial figure. Because he was enthralled by the promise of the Brazilian Communist Party, he was eager to accept any kind of support, no matter where it came from. He worked for a Nazi-supported newspaper, Meio-Dia. The Soviets proved to be useful allies, and Amado developed an affection for the U.S.S.R. In 1951, he won the Stalin Peace Prize, and enthusiastically crossed the Iron Curtain to accept it. Even when history caught up with Stalin, exposing his atrocities, Amado preferred to ignore, rather than deny, his support for the infamous leader.

As far as his books are concerned, Amado’s leftist politics are most significant for turning his gaze toward the marginalized, neglected, and the oppressed. His books are particularly affectionate toward workers, the poor, the homeless, and are most critical of landowners and powerful elite. Amado remembered being galvanized by Dickens' David Copperfield as a school boy, and Dickens would always resonate to him as a socially-purposeful and adventurous writer. Amado is notably interested in women, no small feat in Latin America, a land conducive to the prevalence of machismo. Indeed, his female characters are some of his most memorable, powerful, and complex.

The Violent Land (1943), brings to life the brutal world of cacao-growing in Brazil. Amado, having grown up the son of a cacao-plantation owner, considers this novel to be most dear to him. It mostly follows the violence, swindle, and exploitation on which the industrial interests of his time necessarily operated. Critical of power, lover of the common, Amado urged miscegenation and embracing Brazil’s African heritage. This was an important issue to take a stand on, and one that matters very much to Brazil, a country profoundly affected by racism.

The Violent Land (1943), brings to life the brutal world of cacao-growing in Brazil. Amado, having grown up the son of a cacao-plantation owner, considers this novel to be most dear to him. It mostly follows the violence, swindle, and exploitation on which the industrial interests of his time necessarily operated. Critical of power, lover of the common, Amado urged miscegenation and embracing Brazil’s African heritage. This was an important issue to take a stand on, and one that matters very much to Brazil, a country profoundly affected by racism.

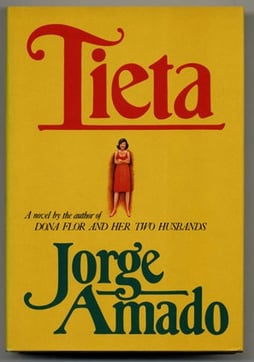

Amado’s writing is attuned to the demotic speech and regional dialects of Brazil. His books are often melodramatic, rich in dialogue and plot and make for a great adaptation for the stage or screen. His book Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon (1958) made for a popular TV show in Brazil in the 1970s. Amado’s fiction has been widely embraced by the people of Brazil, which writer Mona Hatoum said, is “a country where people don't read much, where there is no literary tradition, although there are great writers." Some have argued that this accessibility and popularity made academics reluctant to esteem him too highly.

Politics of all kinds — of Brazil, of the globe, of aesthetic evaluation — will never unwind from the work and legacy of Jorge Amado. Nonetheless, his writings helped forge a national artistic tradition, one made visible to the entire world of readers and storytellers. No matter one’s personal politics, that’s a hard policy to object to.