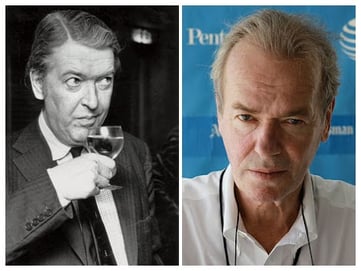

There’s hardly a more memorable father-son duo in modern literature than Kingsley and Martin Amis. “Duo,” though, may not be the most accurate term. The pair never worked together, nor did they agree as far as art was concerned. In fact, each man was distinct in temperament and personality, writing novels unique to his own aims and tastes. Differ as they may, both have offered a powerful portraits of their times, with rich narrative voices to bring their visions to life.

Kingsley Amis was a novelist of the British postwar era, striking fame with his 1954 novel Lucky Jim. Martin, whose latest effort came out in 2014, has captured the '80s onward, using his familiar America and Britain as the backdrop for his wry and sardonic novels. Each author may have been interested in kinds of cultural satire, but that does not make them redundant or even similar. For what it’s worth, Kingsley himself was not much a fan of his own son’s work.

Kingsley Amis was a novelist of the British postwar era, striking fame with his 1954 novel Lucky Jim. Martin, whose latest effort came out in 2014, has captured the '80s onward, using his familiar America and Britain as the backdrop for his wry and sardonic novels. Each author may have been interested in kinds of cultural satire, but that does not make them redundant or even similar. For what it’s worth, Kingsley himself was not much a fan of his own son’s work.

This case is scarcely the first time in history a father and son didn’t see eye to eye. Kingsley, who died in 1995, was an old-time, James Bond-era, Oxbridge-educated Englishman. He matured, like many of his generation did, into a Thatcherite tory. Kingsley was also a prodigious drinker, perhaps one of the most spirited imbibers of all time (if such a thing could be said at all). He wrote brilliantly of the pleasures and joys of booze, and even penned a helpful piece on how to survive a hangover, at once humorous and practical: “Immediately on waking, start telling yourself how lucky you are to be feeling so bloody awful,” he said, encouraging us to remember that we have at least survived.

Martin, who knowingly refers to himself as "the only hereditary novelist in the canon,” still retains a characteristic, English pessimism. His politics are different than his father’s were, and his aesthetic sensibility differs just the same. In a 1990 profile for The New York Times, Martin talked candidly about the elder Amis’ opinion of his book, Money, which many readers have come to consider his most significant work. “I can point out the exact place where [my father] stopped and sent the book twirling through the air,” Martin postulated about his father’s reaction, “that's where the character named Martin Amis comes in. 'Breaking the rules, buggering about with the reader, drawing attention to himself,'” he said, in reference to his inclination toward autobiography.

Overall, differences weren’t an enormous strain on their relationship. Even in matters of their career, Martin’s friend, author Julian Barnes, argued that his father’s distaste gives him an unstoppable verve. “For Martin, it's a hurt that will never go away,” he admitted, but “The good side is, it's acted as a form of vaccination for Martin. If his father, whom he loves, dislikes his books, then it really doesn't matter what any critics say.”

Overall, differences weren’t an enormous strain on their relationship. Even in matters of their career, Martin’s friend, author Julian Barnes, argued that his father’s distaste gives him an unstoppable verve. “For Martin, it's a hurt that will never go away,” he admitted, but “The good side is, it's acted as a form of vaccination for Martin. If his father, whom he loves, dislikes his books, then it really doesn't matter what any critics say.”

Martin, who continues to write at the age of 67, is one of the most established writers in the UK, and his fame occasionally dips into notoriety. As a write-up in The Guardian titled “Why we love to hate Martin Amis” explained, Amis is a public intellectual that Britain can’t get enough of—whether it’s by attraction to his gorgeous prose, or revulsion at his stereotypically male egotism. But if his father’s coldness didn’t stop him, it’s unlikely any turn of personal or public opinion could. The Amises show us how even something as powerful as family can be complicated by the strength and magic of books.