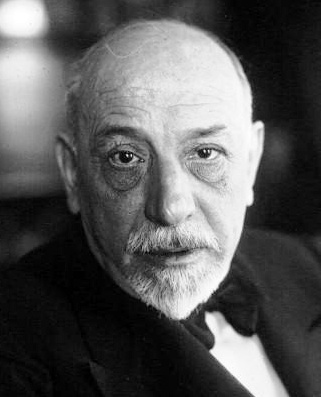

While the Nobel Prize in Literature does not explicitly aim to single out the most influential writers of a given generation (per Alfred Nobel, its purpose is to reward “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”), that it should do so seems inevitable. The most outstanding work, after all, frequently proves to be the most read and most imitated. And indeed, that the Nobel sometimes helps to define the chain of literary influence from one era to the next can be one of the most gratifying things about the list. It is by this metric that Luigi Pirandello, the masterful Italian playwright, can be considered one of the most intriguing Nobel laureates, with his writing directly and obviously influencing at least three other future Nobel winners: Samuel Beckett, Albert Camus, and Harold Pinter.

Pirandello was born, lived, and wrote in Italy, moving between Palermo, Rome, and elsewhere over the course of his life. His father pushed him in the direction of a technical education, but Pirandello—obsessed from a young age with Italian folklore—could not be kept away from the study of literature. He eventually abandoned the sulfur mines of his father and earned a doctorate in Romance Philology. His personal life had an air of the Realism and Naturalism that pervaded the theater of the previous century. His relationship with his father was deeply strained, he broke an engagement with his cousin and married Antonietta Portulano who would eventually grow mentally unstable leading to her institutionalization, and by some accounts, he was saved from suicide only by his dedication to the theater. What ultimately separated him, then, from writers like Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg was that where they reexamined the role of everyday tragic events in the theater, Pirandello was a student of the theatrical logic that governed day-to-day life.

Pirandello was born, lived, and wrote in Italy, moving between Palermo, Rome, and elsewhere over the course of his life. His father pushed him in the direction of a technical education, but Pirandello—obsessed from a young age with Italian folklore—could not be kept away from the study of literature. He eventually abandoned the sulfur mines of his father and earned a doctorate in Romance Philology. His personal life had an air of the Realism and Naturalism that pervaded the theater of the previous century. His relationship with his father was deeply strained, he broke an engagement with his cousin and married Antonietta Portulano who would eventually grow mentally unstable leading to her institutionalization, and by some accounts, he was saved from suicide only by his dedication to the theater. What ultimately separated him, then, from writers like Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg was that where they reexamined the role of everyday tragic events in the theater, Pirandello was a student of the theatrical logic that governed day-to-day life.

In some ways, the pervasive idea that came to define the great dramatist’s plays was the notion, as Nobel spokesperson Per Hallström elaborates, of the “illusory nature of the personality.” While the idea was not new even in his day (Shakespeare himself notes that “all the world’s a stage” centuries earlier), in Pirandello’s deft hands the idea practically becomes its own aesthetic. Perhaps his most famous work, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921), doesn’t just break the fourth wall—it shatters it and hides little pieces of it all around the theater. By depicting a theater rehearsal interrupted by the eponymous ‘characters in search of an author’, Pirandello troubles the relationship between performance and real life. When, at the play’s end, we find the director wondering seriously whether the various 'characters’' deaths have been in earnest or part of the performance, we can’t help but notice the way that crucial question applies to every moment of day-to-day life.

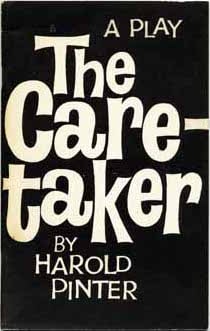

To chart the play’s running time, then, is to measure the span of time in which the Theatre of the Absurd (a tradition that dwells on existentialism and anxiety over the implications of a universe without meaning) was born. In this way, we can trace a line straight from Pirandello to three other Nobel Prize-winning playwrights: Albert Camus, Samuel Beckett, and Harold Pinter, each of whom would, in his own way take up the absurdist mantle. Where Beckett focused on the breakdown of rational communication and Pinter focused on the irrationality of human behavior, Camus worked in an explicitly philosophical mode, tackling the paradoxes of human existence. In this way, we can see how Pirandello’s success gave rise to not one but (at least) four Nobel Prizes, giving us a blueprint in the process for tracing literary influence through the 20th Century and beyond. That we can do so reveals one of the sometimes forgotten joys that come with studying this list of esteemed writers.

To chart the play’s running time, then, is to measure the span of time in which the Theatre of the Absurd (a tradition that dwells on existentialism and anxiety over the implications of a universe without meaning) was born. In this way, we can trace a line straight from Pirandello to three other Nobel Prize-winning playwrights: Albert Camus, Samuel Beckett, and Harold Pinter, each of whom would, in his own way take up the absurdist mantle. Where Beckett focused on the breakdown of rational communication and Pinter focused on the irrationality of human behavior, Camus worked in an explicitly philosophical mode, tackling the paradoxes of human existence. In this way, we can see how Pirandello’s success gave rise to not one but (at least) four Nobel Prizes, giving us a blueprint in the process for tracing literary influence through the 20th Century and beyond. That we can do so reveals one of the sometimes forgotten joys that come with studying this list of esteemed writers.