When Sir Malcolm Bradbury died in 2000, it seemed the entirety of London literary culture mourned. Here was a man who had written a trove of delightful novels, taught countless students, and advocated tirelessly for the advancement of the written word. His death sparked something different from the usual public grieving process. Where many authors are lamented because there will be no more books, this man was mourned because there would be no more Bradbury.

To many, Bradbury went about life with a contagious grace and energy. The day after his passing, one colleague remembered the author as “a person of unusually broad humanity: compassionate in his politics, generous with his time and attention, courteous in his habits, by turns amusing and grave in his talk, and expansive in his interests.” His gregariousness was also a matter of legend. In the wake of his death, another friend recalled his “wonderful sense of humour. He came first at the party and was the last to leave."

To many, Bradbury went about life with a contagious grace and energy. The day after his passing, one colleague remembered the author as “a person of unusually broad humanity: compassionate in his politics, generous with his time and attention, courteous in his habits, by turns amusing and grave in his talk, and expansive in his interests.” His gregariousness was also a matter of legend. In the wake of his death, another friend recalled his “wonderful sense of humour. He came first at the party and was the last to leave."

He came to eminence with the release of his first book in 1959. It was a satirical campus novel, and Bradbury would be drawn to the academic landscape for much of his life and work. His most appreciated novel, The History Man (1975), concerns a far-left sociology professor and his escapades. The story ends with the protagonist surrendering his radical bent to ally with the swelling conservative tide of his time.

In the obituaries and recollections penned in his memory, people wrote as much of Bradbury’s character as they did of his work. As a teacher, he was well-respected, instructing both classes in American Studies and running the MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia. One colleague purported there to have been no program to have produced a higher rate of published authors. Among Sir Malcolm Bradbury’s own students were modern day superstars like Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro.

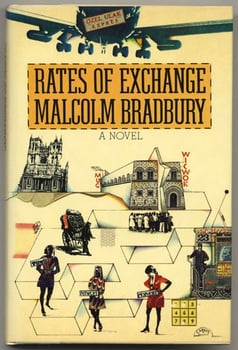

Bradbury was also renowned for his activity in the public literary scene. He was reluctant to turn down invitations, and enjoyed any opportunity to celebrate or advance the art of fiction. He leant his time to the committee for the Man Booker Prize as well as the British Counsel. As a prolific writer, Bradbury wrote many book reviews in his career (one colleague estimated as many as a thousand), and had a reputation for being supportive of others, even to a fault. Kazuo Ishiguro recalled the Bradbury’s dejection after receiving a bilious review from Martin Amis in the Observer for his novel, Rates of Exchange. Yet years later Bradbury would write glowing praise for Amis’ novel, The Information. For Bradbury, writing was often too serious to let the personal interfere.

Bradbury was also renowned for his activity in the public literary scene. He was reluctant to turn down invitations, and enjoyed any opportunity to celebrate or advance the art of fiction. He leant his time to the committee for the Man Booker Prize as well as the British Counsel. As a prolific writer, Bradbury wrote many book reviews in his career (one colleague estimated as many as a thousand), and had a reputation for being supportive of others, even to a fault. Kazuo Ishiguro recalled the Bradbury’s dejection after receiving a bilious review from Martin Amis in the Observer for his novel, Rates of Exchange. Yet years later Bradbury would write glowing praise for Amis’ novel, The Information. For Bradbury, writing was often too serious to let the personal interfere.

Bradbury also took great enjoyment from conversation. He hosted large parties, dedicated to drink and discussion, whenever he could. His taste for invigorating intellectual talk extended to the classroom, combining with his generosity to inspire a generation of students.

Bradbury died the year he was knighted, an honor bestowed not only for his writings but for his wide-ranging efforts in the service of literature and fiction. It’s not unusual for an author to inspire other writers with his books, but to do so with one’s character and energy is a far more rarefied and remarkable legacy.