When beloved writer and illustrator of children’s books Maurice Sendak passed away in 2012, it was Stephen Colbert who best summed up the sentiment that accompanied Sendak’s passing. “We are all honored” he said, “to have been briefly invited into his world.” And indeed, Sendak’s most beloved works, like Where the Wild Things Are (1963) and Brundibar (2003), were invitations to worlds wholly separate from this one: worlds that were at once startling and beautiful, inviting and grotesque, smartly crafted and whimsical. It wasn’t just the worlds populated with wild things, however, to which Sendak invited his readers.

By the time Maurice Sendak won the Caldecott Medal for his most novel text, Where the Wild Things Are, he was already being heralded as a unique and subversive force in the world of children’s literature. The Brooklyn-born, Jewish illustrator had illustrated such works as Ruth Krauss’ Charlotte and the White Horse (1955) and was, all evidence suggests, coming into his own as a storyteller. When he was catapulted to children’s lit stardom he could, no doubt, have built an entire career on repeating the successes he had already known. But, never one to shy away from pushing the envelope, Sendak only became more adventurous in his work.

By the time Maurice Sendak won the Caldecott Medal for his most novel text, Where the Wild Things Are, he was already being heralded as a unique and subversive force in the world of children’s literature. The Brooklyn-born, Jewish illustrator had illustrated such works as Ruth Krauss’ Charlotte and the White Horse (1955) and was, all evidence suggests, coming into his own as a storyteller. When he was catapulted to children’s lit stardom he could, no doubt, have built an entire career on repeating the successes he had already known. But, never one to shy away from pushing the envelope, Sendak only became more adventurous in his work.

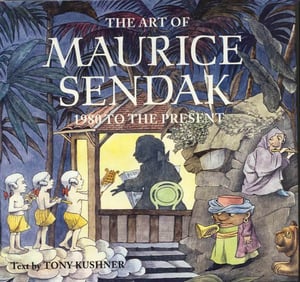

By the 1970s, Sendak was so in-demand that he essentially had his pick of projects. He spent much of his time designing sets for productions of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker (1892), Mozart’s the Magic Flute (1791), and others. He worked for a time as an advisor for the Children’s Television Workshop (during the early days of Sesame Street). Though these endeavors might have had the potential to detract from his output as a writer of children’s books, they proved to be quite the opposite. His set-design work on The Nutcracker was ultimately parleyed into a 1984 book of the same name, and a project involving Jim Henson that he began at the Children’s Television Workshop turned into one his last published works, Bumble-Ardy (2011). Even Brundibar, which was illustrated by Sendak and written by Pulitzer prize-winning dramatist Tony Kushner, began with work on the sets for a holocaust opera of the same name.

The seemingly roundabout nature by which many of Maurice Sendak's children's books came to fruition underscores a truth that is, perhaps, uncommon among children’s authors and illustrators. While Sendak was constantly welcoming children to worlds of his own creation, he was subtly and simultaneously welcoming them to the worlds of art, literature, and history. Case in point, while Sendak has cited Disney’s Fantasia as being a major influence on his art, he has asserted that “(his) gods are Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, and Mozart.”

The seemingly roundabout nature by which many of Maurice Sendak's children's books came to fruition underscores a truth that is, perhaps, uncommon among children’s authors and illustrators. While Sendak was constantly welcoming children to worlds of his own creation, he was subtly and simultaneously welcoming them to the worlds of art, literature, and history. Case in point, while Sendak has cited Disney’s Fantasia as being a major influence on his art, he has asserted that “(his) gods are Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, and Mozart.” While the works of Melville and Dickinson are, generally, not the sorts of things that make for good children’s reading, it takes a special kind of talent to recognize that the truths around which such authors structure their works are just as true for children as they are for adults. While Sendak’s works aren’t the only ones with fantastic and imaginative worlds, they are uncommon in their capacity to root those worlds in the fundamental truths of life and art.